Villa Dolores by Rafael Mahdavi

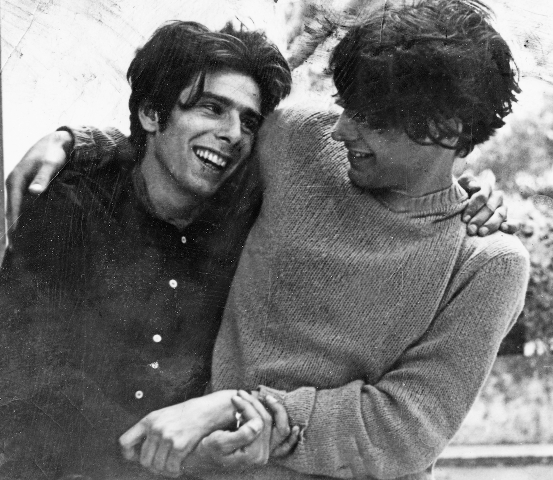

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 30, 2017

Villa Dolores

By Rafael Sinclair Mahdavi

Published, 2017, 173 pages

Create Space

Available through Amazon

ISBN:1548468045

Relatively speaking Villa Dolores, a memoir of coming of age by the artist Rafael Mahdavi, is a slim volume of 173 pages.

Yet it took me several weeks to read off and on during an intensive period of travel this fall. That started in West Dennis on Cape Cod, continued during a busy week of theatre in New York, and was completed while in Portugal for a wine tour.

There was a time when I was a fleet and avid reader. That has gradually ground to a crawl. The venture into Rafael’s book was a slow, flavorful, colorful and insightful poetic experience. The pages spoke to me in his characteristic stutter start cadence. It felt like he was taking with me about his life, work and philosophy of the arts. This book offered many realizations about a complex person, artist, and fellow traveler, whom, with absurd conceit I presumed to know.

We share aesthetic adventures and a circle of friends that included his former wife, Carter’s deceased sister, Berkeley Bottjer. During a memorable evening, when they were living in Wellesley, Carter disappeared. It was her habit to retire early, and I sat up with our host, Berkeley, and one of Rafael’s best friends, the theatrical set designer, Carl Eigsti. They met that night and later married.

During that time Rafael was commuting from teaching and a studio in Paris. Carter was a producer for WGBH in Boston. There were gatherings that I attended.

During a visit to Paris we selected work for a show at New England School of Art & Design. I managed to arrange a simultaneous show of works on paper at the French Library. I published an essay on the shows for their magazine. He brought the paintings rolled up as a carry on. To avoid customs they were returned as uninsured "table cloths." It was clever to have an international exhibition with essentially no budget.

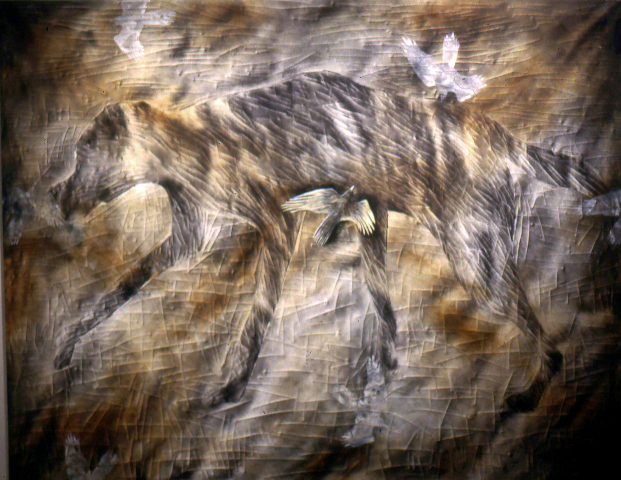

Artists must be resourceful to survive and purchase materials. In NY and Paris, Rafael painted sets for theatre and opera which is how he knew Carl.

After art school in the 1960s, penniless, he moved to Paris and avoided the draft. He was scratching out a living under the table when Interpol knocked on his door. They were impressed that he was fluent in French with seemingly no accent. His passport was confiscated but they left him alone. He got it back later through a general amnesty. For many years, he taught at the Paris branch of NY’s School of Visual Arts.

Nothing in a true artist’s life is ever wasted. When we talked the other day by phone from his villa in Burgudy, he mentioned how scene painting had become an aspect of his works which are notable for narrative content. Like the Old Masters, whom he has studied since adolescence, compelling art must be about something. It is informed by life and builds on history. We discussed how that respect for technique, knowledge and history is absent from a contemporary art world which is about vice and fashion.

We compared similar positions on the outskirts of the art world creating to please our inner need now with a sense of legacy. We noted an uncanny confluence of writing memoirs as a form of permanence when facing the unknown. We share fatalism and fear the quality of life for doomed earth’s ever more stressed inhabitants.

Like his painting, which I have long admired, curated and written about, this new aspect of literature has me stunned, humbled and stopped in my tracks.

The book has many brief chapters, each an astonishing, well polished vignette. Often there are horrors of one kind of another condensed to two or three pages. The prose is stark, precise, sharp and sparing. It is also rich in detail particularly from a man now 71 recalling so vividly the experiences of early childhood and adolescence. There is also the exuberance and joy of growing up at the Villa Dolores. There was an annual summer ritual when Rafael, his brother Conrad and their pals, built cabanas on the beach.

At the fragile age of ten innocent childhood came to an end. He was tossed not into the street by his expatriate parents, but, as we learn, what is far worse, boarding school. There were several of which the worst, a true nightmare, was Theresianum in Vienna. Those passages read like a Dickens novel.

It was the school his Iranian born father, Mohammed, attended. Later he earned a Ph.D in International law. His mother, an American, wrote for the New Yorker and other magazine as well as publishing 11 books for Knopf and Little Brown. He recalled renowned authors who came to visit her.

They met at a poetry reading at the YMCA on the upper East Side of New York. As he writes “They bought a bottle of Scotch and checked into a hotel for a few days. Then they moved to Mazatlan in the province of Sinaloa in Mexico.” When Mohammed married an American and non Muslim he was disinherited. There would be some reconciliation and time in Iran but his father was secular. Rafael states that he is an atheist but rooted in spirituality which is expressed in his work.

Rafael was born in Mexico and a year later Conrad who was named for the novelist. His father went to work for UNESCO in Paris. But he quit when the job took up too much of his time.

There are painful passages in the book including the alcoholism of his father. As he told me it went with the territory of expats of that era. Because his brother and sister left boarding school which they disliked and went home to their parents. Rafael, as he puts it, toughed it out. He was only home for summers at the idyllic Villa Dolores in Mallorca. The family moved there in 1950.

The distance, discipline, and suffering of Rafael allowed him to see his parents more objectively than his siblings. Clearly, this is difficult to write about. There is the need to be honest but also discreet and protective. For writers who discuss their family there is concern about who owns the rights our lives? What obligation, in telling the truth, is there to siblings and extended family? To what extent does modification and self censorship diminish the narrative? There is always a fine line which Rafael has navigated with adroit tact.

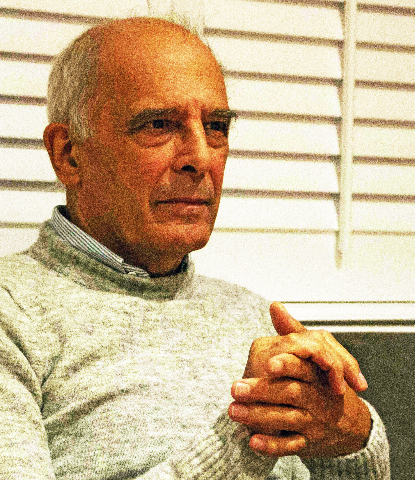

Today, Rafael spends half of the year in rural France where he paints and makes metal sculpture. The other half is on a Cycladic Island and Athens during stretches of bad weather.

When enrolled in Vienna he didn’t speak a word of German. With total immersion, and survival of regular corporal punishment, he soon became fluent. He and several other boys organized an escape. They were caught, brought back, and caned to an inch of their life. During a vacation period he was confined to infirmary and through semi-deliberate malpractice came close to death. There would be death in his young life, a family retainer and pedofile, who drowned. Then a first love died. It is among the most poignant of the chapters in this thrilling, tender and wonderful book.

Of course there are the first threads of art. Quite young he was a master of technique and rendering. It seems that his art teacher in Vienna was an idiot and he was actually accused of art theft. There was no ironic understanding that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

"I meticulously copied a post card of a boy with a torn straw hat in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston." He recalled. "They refused to believe that I had painted it."

Early visits to the Prado and Louvre were life changing. He still visits his “friends” standing long and looking hard into masterpieces. It is a birthday ritual and he promises to send me a photo of a recent variation on “Las Meninas” by Velasquez. It made me recall also staring long and hard at it, as well as, an hour or more in front of “Garden of Earthly Delights” by Bosch. And what can one say of the Prado’s black paintings by Goya with their utterly sublime madness?

By phone yesterday I was enchanted my his signature stutter step discourse. Thoughts wind up and, after a pause, are delivered in a staccato outburst like a machine gun. The words pierce the air and cut down straw dogs of chillery, shuck and jive, chicanery, and every shape or form of utter bullshit. After a life trudging about in the trenches of the arts there is a lot of shit on one’s boots.

With a massive emotional outburst he described it all as a matter of luck. Just to have the tough and enduring genes to endure decades of living on the edge, cutting a huge chunk out of the sweet cherry pie of life, enduing temptations and, in his case, being a loving and supportive father to a son, Alexander, and daughter, Carter Ann. He is thankful for the galleries and museums that showed the work and collectors who bought it.

"I do not believe in pre destination" he explained passionately. "It's all luck. People who hang out and schmooze at literary events and vernissages, which I hate, get published and shown. We all know that they are not necessarily the best writers and artists. You have to make work that publishers and gallerists can sell. I have been lucky to have my work shown and appreciated. Luck, that's all it is. Pure luck."

We can only do the work and what happens after that is not in our hands. The world spins and clinging to it we are flung out ever further to its periphery. Which, clutching that brass ring, is pretty cool come to think of it. Most committed artists accept that the game is rigged.

Surprisingly, this citizen of the world proclaims that “I love America.” Perhaps he can say that from the distance of Europe. For those of us who read the daily Tweets it’s a different story.

There is his remarkable facility with languages: English, French, Spanish, Catalan, German and now Greek. “I used to read and write in other languages but I found that now it is best only to read in English.”

That unique patois is a confluence of all those languages and accents. With age it is ever more difficult to keep them separate and distinct.

This book is a triumph with others soon to follow. It follows “Staying Alive/ Permanecer en vida” 2010, with photographs and poems in English and Spanish. A sequel to the autobiography has already been written. Older manuscripts and novels are being edited and prepared for publication.

It is easy and arrogant for the young with freshly minted BFA and MFA degrees to proclaim “I am an artist.” At our age it is better to say that “I write” or “I paint.” It is for others to say if we are artists. From my vantage point I have always regarded Rafael as a rare and true artist. Now I must add, and a heck of a writer.

Resulting from our too brief conversation about the book I had questions. There is a lot of depth about his brother Conrad and their horrors in boarding school. I asked for an update and a bit more about his artist sister.

By e mail this was his reply.

Hi

My brother Alex Conrad was also born in Mexico in 1947, went to Amherst College and the International Diplomatic Academy in Vienna. In the late sixties, he wrote a book called Bungling Pedro and Other Majorcan Tales, published by Knopf. Later, in the seventies, he was the manager of the Rizzoli bookstore on 5th Avenue in NYC. In the 80's he was the administrative director of the American Center for Students and Artists in Paris. In the early 90's he moved to Prague where he opened an international 5-language bookstore called U Knihomola (The Bookworm in Czech) with its cafe, which became a well-known watering hole for artists and diplomats. Now at 70 he lives in central France, in the Yonne department. He is married to Anne Delaflotte, a French novelist with five books (published by Gaia) to her name. My brother is also a world expert in ink pens.

My sister Florence is a painter and engraver, and an expert in Japanese calligraphy. She was born in Vienna in 1949, attended the renowned Madrid art school Academia San Fernando and then the national art school (Academia de Bellas Artes) in Barcelona. Later in Paris she studied etching at the Stanley Hayter School. She currently lives in Edinburgh.

As for yours truly, for the last ten years I have been living with Euphrosyne Doxiadis, a painter and writer, well known for her book The Mysterious Fayoum Portraits, published by Thames and Hudson in London, by Abrams in NYC and by Gallimard in Paris. She has lectured at the Getty, the British Museum, and last month at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow where she also gave an encaustic workshop. We divide our time between Burgundy, Cylcadic Islands and Athens.

And that's the way it is, folks.

Rafael