Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III at 83

Former Curator of Classical Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 03, 2008

During what was truly another era, from 1957 to 1996, Cornelius Vermeule (August 10, 1925- November 27, 2008) was the Curator of Classical Art for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It was the most important such post in an American museum and placed him on the short list of foremost global scholars of Greek and Roman art. His particular specialty was numismatics which he started to collect when he was nine-years-old.

Like the Brain Trust of Roosevelt, Vermeule was a "dollar a year man" for the MFA. The great curators of his generation came from old money and nobody actually lived on their salary. He often donated the equivalent of his earnings to the collection; usually for acquisitions of coins.

Before joining the Museum of Fine Arts Vermeule had chaired a department at Bryn Mawr that included Rhys Carpenter and Richard Lattimore. His wife Emily was a former student at Bryn Mawr. A great linguist, in addition to Classical Greek and Latin he was fluent in modern Greek, Turkish, French, Italian, German and Japanese. His conversation was routinely laced with jokes and phrases in all of these languages.

In the old paradigm of great museums, curators such as Vermeule, with deep endowments presiding over priceless collections, often wielded far more clout and influence than museum directors who were viewed as mere figureheads. The real seat of power in museums resided in the pecking order of its curators. The authority of Vermeule was rivaled only by that of Jan Fontein the curator of Asian Art. A third spoke of the wheel was John Walsh, Curator of European Paintings, who, when passed over as director of the MFA, departed to run the nation's wealthiest museum, The Getty Museum in Malibu. It was speculated that Walsh would miss the prestige of the MFA and come back to Boston, but that never happened.

Vermeule first served under Perry Townsend Rathbone. When Rathbone was forced to resign because of a botched acquisition of an ersatz Raphael portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga there was a brief pratfall when George Seybolt, chairman of the board of trustees, appointed an unknown, Merrill Reuppel as director. He made several unpopular suggestions shortly after he arrived which caused a conspiracy leading to his removal. Briefly, Vermeule served as acting director before Fontein evolved from acting to full time director. In a series of late night leaks, to Robert Taylor of the Boston Globe, Vermule was often alleged to have been the deep throat of the affair.

During his stint as acting director of the MFA Vermeule might well have remained had he chosen to. But it was not his style or inclination to be bogged down by the position. Although one of the foremost classical scholars of his generation he was also a free spirit and merry prankster.

For two and a half years in the 1960s, shortly after graduating from college, I was an intern in the Department of Egyptian and Near Eastern Art of the MFA. Our suite of offices was adjacent to those of the Classical Department. There was a door between the departments which by an unwritten rule was left open. Only on rare occasions, for a private meeting, would Cornelius close the door.

Compared to the rather dry and dusty daily life in the Egyptian Department it always seemed that they were having so much fun next-door. One summer, Jim Jacobs, a student of Emily Dickinson Townsend Vermeule, at Boston University, became an intern. We have been friends ever since. His duties were rather odd compared to mine. One of them was to take Cornelius' dog, a Dalmatian named Diocletian, for walks. Sometimes I tagged along. Jim was also responsible for removing the salts from the vitrines when they turned red. He would bake them in a kiln until they were blue again and replaced them in the cases. The rest of the time he studied coins.

We would take strolls through the galleries and I would talk about the Egyptian treasures and he would discuss the Classical works. I had a project to reconstruct the nose of Prince Ankh Haf but my boss, Dr. William Stevenson Smith, was not amused. Jim thought it was hilarious. I still have the drawings.

During one of our strolls we stood before a virtine and Jim asked me what I saw. We were looking at a terra cotta classical figurine with her arms outstretched. Across her arms was another broken arm. "Do you get it" Jim asked? He explained that it meant "I Wannah Hold Your Hand" which was then a popular song by the Beatles. It seems that this was Cornelius's ongoing joke case. It would be changed from time to time and none but a few were hip to what was going on.

Once I was studying a case of black and red figure classical pottery just outside our offices. In particular, I was examining a painting inside a kylix that depicted a man enjoying anal intercourse with another man bent over beneath him. Over my shoulder Cornelius asked if I read Greek? He then translated the two word inscription that read "Hold Still."

Looking around at the collection of pottery he offered a quick clue to finding the erotic ones. "Look for the smudge marks on the glass" he explained. "That's where the foreheads of the hot little faces strain for a better look." It was information I always delighted in sharing, in later years, when I took my students on tours of the museum.

While I was in graduate school at Boston University I took a course with Cornelius. It was open to all of the fine arts graduate students in the Boston area. We met each week at the museum and it seemed that Cornelius was always in the middle of something when we arrived for a class. There was little if any preparation or agenda. Most often we just went out into the collection and he would start talking. We all did research papers which included giving a talk in the galleries. Mine was about putting the nose on the Ankh Haf. Cornelius liked it, and I got an A.

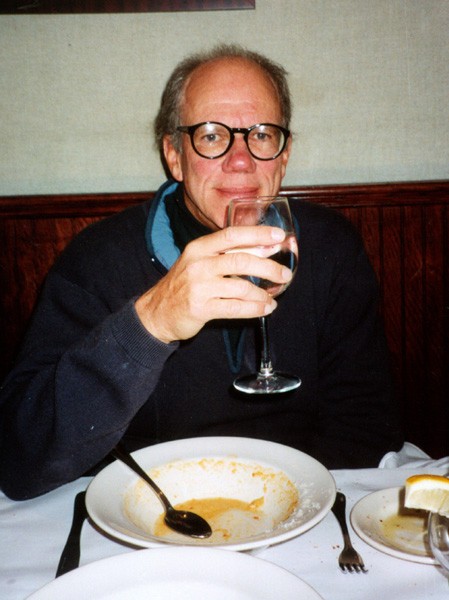

Long after I had left the museum, in later years, I would call Vermeule for quotes or off the record leads to stories. In April, 1989, I visited and interviewed him for my column in Art New England. The photos that accompany this story were taken that day. As usual, he was funny and playful. He was collecting toy dinosaurs as well as rare coins. He signed a couple of his books and gave them to me as a present. They were on numismatics.

After Cornelius retired, the MFA hired Malcom Rogers as director. He arrived with a mandate to shake up the old boy network of curators. The Rogers mantra was "One Museum." There was a lot of dissent when he fired Jonathan Fairbanks and consolidated departments. Although invited to stay on as Chair of the new Art of the Americas department, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. soon departed for the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard.

In the midst of the turmoil about Rogers and his unpopular changes at the MFA, I made a call to Cornelius. But I was shocked and saddened when he informed me that "We are not well Charles." His beloved wife Emily died not long after. It was our last conversation and so unlike how I remember him. In the current corporate, bottom line museum world, there will never again be curators who take their dogs to work.