Liu Zheng in Context

Related Photography Exhibitions at Williams College Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 04, 2008

Beyond the Familiar: Photography and the Construction of Community

Curated by John Stomberg

Williams College Museum of Art

Beyond the Familiar through March 8, 2009

With the debut exhibition of the recent acquisition of the 120, silver gelatin prints in "Liu Zheng: The Chinese" the curator and deputy director of the Williams College Museum of Art, John Stomberg, created a context for the work with several galleries of studies of related photographic book and album projects from the 19th century through ones that are in the process of being published.

An advantage of being a neighbor to the three major museums in Northern Berkshire County- Mass MoCA, The Clark Art Institute, and the Williams College Museum of Art- is the opportunity to absorb and study exhibitions and installations through repeated visits and increments of time. Mostly, this encourages appreciation of the work as we become more familiar, but can also cut in the opposite direction, as strong first impressions do not sustain under the scrutiny of in depth examination. Generally, it takes time to fully probe the depth, or lack thereof, of works of art.

In this case I had already visited and viewed the current exhibitions of photography several times before spending time with the curator. Our primary focus was on the installation by Liu Zheng. This artist and in depth body of work was unfamiliar so it was significant to share Stomberg's views particularly as this acquisition is intended to form a nucleus for future development.

As we walked through the galleries of related exhibitions Stomberg noted that about 40% of what is on view is owned by WCMA. In the case of some of the recent work in the exhibitions he stated that they hope to acquire examples. But, given the terrible losses of endowment funds in the past year that may be put off until there is some recovery. Just when, of course, is on everyone's mind. While Williams and the Clark have deep pockets, like everyone else, they are not as deep as they used to be. The Liu Zheng acquisition occurred under the wire before the "crash."

We spoke recently with Stuart Chase, director of the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield. The museum deaccessioned two Russian paintings at auction for some $7 million. This occurred during a sale when most of the lots did not make their minimum reserves. Including prior funds, the museum has some $8.5 for acquisitions. So it is a good time to have dry powder although, so far, we have not seen the fire sale in the art market that one might anticipate. There is a reluctance to sell off devalued blue chips and most collectors are holding on as best they can.

While in these hard times it seems inevitable to talk about money, or the lack thereof, Stomberg focused on the aesthetics and issues involved around the balance between documentary photography and fine art. Just where is the tipping point between reporting/ journalism and images that strive for higher ground?

This dialogue started inevitably with wall cases set at an angle that displayed two signature works on the 1930s. "You Have Seen Their Faces" by Margaret Bourke-White and the writer Erskine Caldwell was a sensation and immediate best seller. It had been initiated by an assignment from Fortune Magazine. Simultaneously, Fortune dispatched the team of photographer Walker Evans and the writer James Agee on a similar assignment to report on the devastation of farmers in the South. While the Bourke White/ Caldwell project was successful the editors of Fortune rejected several rewrites of the Evans/ Agee project. When they recovered ownership of the work and published it in the early 1940s the book was a critical and financial failure. It was quickly remaindered having sold just a thousand copies. When it was republished with some revision in 1960 it was hailed as a "classic."

Stomberg referred me to his essay on the debate surrounding the two books in the catalogue "Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain." The exhibition was presented at WCMA last year. His essay summarizes the literature and controversy about the strikingly different approaches. He quotes from the initial reviews, favorable to Bourke White/ Caldwell and harsh on Evans/ Agee, and later critical writing, after 1960, particularly in the 1970s, when the pendulum swung the other way. Essentially, Bourke White strove to be "objective" and "journalistic" by photographing surreptitiously capturing spontaneous, candid glimpses of her subjects. It represented a different approach for her as previously she had photographed factories and industry using dramatic lighting and abstract, formal values. She made a point of not knowing her subjects working through brief "objective" encounters. Yet, the captions of Caldwell deceived readers into thinking they were quotes from their subjects when they were not. Their book had an agenda for social awareness and change. It was the stance of the concerned artist and, as such, had an impact in creating a dialogue at the time.

Evans came to despise the book and approach of Bourke White whom he viewed as exploiting and profiting on the suffering of others. Indeed, she went on to be a very successful photographer at a time when Evans was laid off from the Farm Security Administration and was having difficulty finding work. The approach of Evans and Agee was entirely different. They came to know a few farm families over multiple, prolonged visits. The images of individuals and families are frontal, formal, trusting, and affectionate. The photographs were grouped as a portfolio, without captions, that preceded the text of Agee. While Evans and Agee stated that they were not making art their work and approach was later embraced as a paradigm of modernism. Evans became an influence on much of the documentary photography that followed. There is much evidence of this in the sidebar of exhibitions which Stomberg has assembled.

Unfortunately, the two books and a few images that are key to the critical dialogue of the exhibitions are given too small a proportion of space. While running the Boston University Art Gallery, some years ago, Stomberg organized a massive exhibition of Bourke White's commissioned work in Canada. At the time, we viewed the exhibition together and discussed the images. The documentary photography of the 1930s is a topic that absorbs Stomberg and he discussed hoping to organize a show for WCMA based on artists and writers who worked for Fortune Magazine.

The large gallery devoted to "Beyond the Familiar: Photography and the Construction of Community" was divided into walls and sections sampling well known projects. Most directly related to "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" was the famous Robert Frank (Born Switzerland, 1924) project "The Americans" which was published in France, in 1958, and in the US in 1959. In the late 1940s he traveled extensively in the States producing some 28,000 negatives. He reduced this to the 100 images in the book. In the May, 1960 issue of Popular Photography, the book was renounced "There is no pity in his images. They are images of hate and hopelessness, of desolation and preoccupation with death. They are images of an America seen by a joyless man who hates the country." In an introduction to the book, not surprisingly, Jack Kerouac saw the work differently.

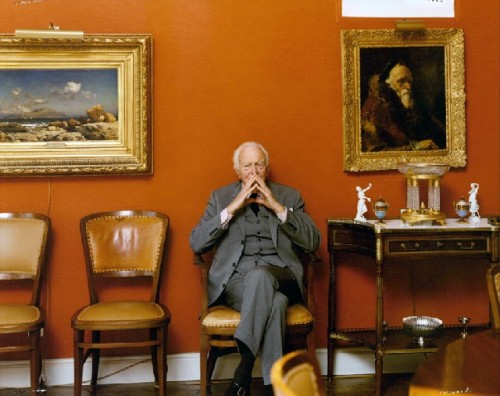

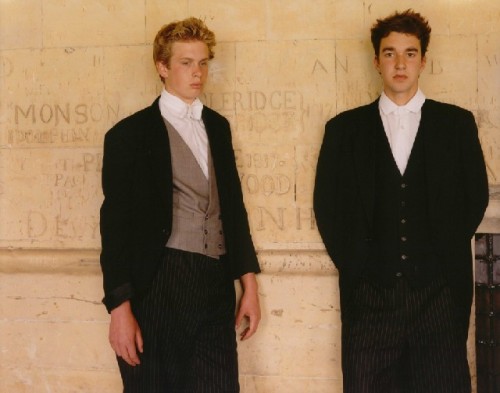

The other selections explore the concept of "Beyond the Familiar." They extend the notion of Evans and Agee living with, befriending, and earning trust from their subjects. Both Barbara Norfleet "All the Right People" and Tina Barney "The Europeans" convey images of the ruling class. In candid studies Norfleet presents the privileged in their natural habitat. They are comfortable with her camera and presence with the implication that Norfleet is one them. Being not of their world, except perhaps for many of the Williams students and alumni, we tend to regard these images with irony. Having come from a biased, liberal education it is instinctive for me to respond to the large format, expensive, and lush images by Tina Barney with an apathy that tends toward disdain. As an artist she seems too much of the world that she depicts. It is hard not to view the prints in the context of post modern, society portraits. Rather like those ghastly, vapid portraits that earned Andy Warhol tons of money. One suspects that the subjects in Barney's images are proud of the way they are depicted. This is work that undoubtedly appeals to Republicans more than Democrats. As F. Scott Fitzgerald said "Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me."

It is the relationship between the photographers and their subjects that gives a special edge to the work of the white South African, David Goldblatt, and his "Some Afrikaners Photographed" (mid 1960s- 1975) and the black South African Zwelethu Mthethwa's soon to be published "Gold Mines" "Sugar Cane" "Mozambique" and "Contemporary Gladiators." One feels a similarity to Norfleet in Goldblatt's treatment of his racist peers but with more of an edge. We have to look hard to feel Goldblatt's social and political position to his fellow Afrikaners during the last gasp of apartheid. It is ironic to note that the scale and production values of the large format color prints of Mthetwa share many confluences with the work of Barney. Their subjects, of course, are on opposite ends of the social and political spectrum. The juxtaposition of Barney and Mthethwa undoubtedly provokes lively debate among students.

While the primary audience for WCMA shows are Williams faculty and students there is also an important outreach to the surrounding community. Stomberg informed me that. through its education program, some 7,000 students from the region visit the museum. There is similar outreach through the Clark and Mass MoCA. What a remarkable opportunity for these students.

Moving on to the next gallery we discussed the "historic" segment of the special exhibitions. We started with images by Felice Beato (English, Born Italy, 1825-ca. 1908) and images from a two volume album "Photographic Views of Japan with Historical and Descriptive Notes, Compiled from Authentic Sources, and Personal Observation During a Residence of Several Years." Stomberg explained that they were displayed from floor to ceiling in a shop. Visitors made selections and these were compiled into albums. Most of these albums have come down through descendants of sea captains who visited Japan.

It was interesting to see the work of the British Pictorialist, Peter Henry Emerson, (English, B. Cuba, 1856-1936) from "Pictures from East Anglian Life" (1888) next to the romantic images of Native Americans by Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952) from his 20 volume set "The Indians of North America." The juxtaposition makes it obvious that Curtis drew on Pictorialism in his romantic images of Native Americans. While WCMA owns works by Curtis, Stomberg borrowed from the Bowdoin College Library because he was looking for specific images.

The Aaron Siskind (1903-1991) "Harlem Document" from the late 1930s seemed quite surprising compared to his better know, more formalist, later work. But even in this series Stomberg pointed out Siskind's interest in abstract elements in a series that strove for, but did not really work, as social commentary. Stomberg stated that WCMA owns the works on view by August Sander (1876-1964) from "Menschen des 20er Jahrhunderts (Citizens of the Twentieth Century)." While vintage Sander prints sell for six figures each the WCMA set was printed by Sander's grandson. The photographer taught his son how to print the negatives and this was passed on to the grandson. Stomberg stated that prints by the grandson are closer to the originals than those printed by the artist's son.. Sander survived the war but his work was condemned by the Nazis. He buried his negatives and lived in obscurity in rural Germany.

This series of related works encourage more prolonged viewing and understanding of the major acquisition of Lie Zheng's "The Chinese." It is what a great teaching museum like WCMA is all about. In that sense we are all students with much to learn. We are grateful to John Stomberg, and Williams, for providing us with this remarkable opportunity.