Holiday on the Aegean Coast: Part Two

Coastal Villages West of Izmir

By: Zeren Earls - Dec 05, 2008

My friends Evin and Mick McCain live in a contemporary housing development on a hill overlooking the Aegean in Zeytinalan, outside of Urla. To get there we drove up winding roads, passing custom-built homes secluded amidst fig and olive trees. Evin met us at the gate and ushered us into the top floor of her two-story house, built against the crest of a hill. Instantly, I was drawn to the sweeping view out the large picture windows; the Aegean's azure waters shimmered at a distance; a family gathered olives off the ground nearby. Then my gaze turned to the interior furnishings. The house was a treasure trove of folk art from throughout Anatolia, collected during my hosts' respective travels -- Evin as a professional tour guide and Mick as an American missionary and teacher since the late 50s. The kilims (flat-weave carpets) were especially enticing.

Evin had lunch ready. Customarily Turks have two cooked meals a day. The olive motif on the table cloth and matching napkins were reminders of the importance of this fruit in these parts, where cutting down an olive tree is punishable by law, and an olive tree is priced separately than the land it occupies. A platter of large artichoke hearts with stems took center stage at the table along with dishes of mixed olives, sliced tomatoes and cucumbers. Cooked in olive oil with fresh dill and eaten cold, the artichoke dish preceded dessert, which was melon. Grilled chicken chops, home-made noodles and green beans followed the beginning soup course, a typical order in Turkish cuisine, where cold olive oil dishes follow the hot meal. A serving of fruit precedes optional coffee.

During my two-day stay we explored several ancient sites, beginning with the closest one in Urla, the Ionian city of Clazomenae. Most of the artifacts found here have gone to the museum in Izmir. However, a most interesting aspect of this visit was the olive oil production dating back to 600BC. Digs in 2005 have revealed an industry, including wells carved into rocks for making and storing olive oil in a zone outside of city walls. With expert help from local builders, a replica has been made into a small museum, where one learns about olive oil production, which depended on manual labor before mechanization. Large mill stones crush olives into a paste, which goes into sacs made of goat hair. A heavy stone is lowered over the stack of sacs, pressing out the oil along with the olive's dark juice, which fills two stone wells half full of water. Adding hot water helps the oil to float, which is then skimmed into a third well to settle before it is bottled. This first pressing is known as "cold pressed oil". Plans are underway to create a child-size version of the museum, where children would arrive with their own olives and process it into oil.

The area is rich in plant life and vegetation. Before returning home we went to the farmers' market, where Evin, as a regular, seemed to know most of the vendors. While she stocked up on fruits and vegetables grown in the region, I enjoyed walking amidst mounds of grapes, melons, pomegranates, black and green figs, fresh black-eyed peas and many edible herbs and weeds, in addition to strings of dry tomatoes and red peppers hanging from the stalls.

Also rich in fishing, the coast boasts numerous fish restaurants. For our evening meal we patronized one at the harbor, owned by Evin's son. Here we enjoyed grilled sea bream, preceded by assorted appetizers of grilled and fried squid, fava (mashed broad beans), fresh black-eyed peas and arugula. Dessert was a choice of mastic flavored pudding or ice cream roll coated with dried figs, in addition to black grapes, all regional specialties.

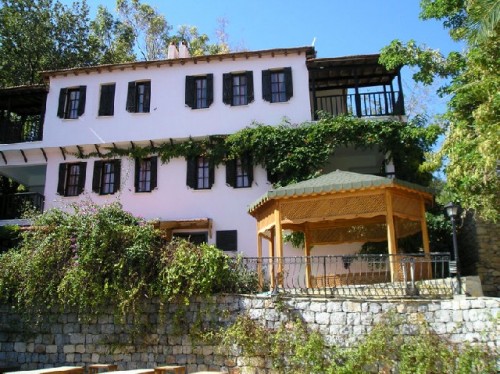

The next morning we drove to Urla, the oldest town on the peninsula, with a population of 41,000. Many of the houses, formerly owned by Greeks, have not been fully restored and give the town an aging veneer. The town has three mosques of the late fifteenth century and an ablution fountain with a domed ceiling, painted in the seventeenth century. An old summer resort for Izmir residents, Urla has, in recent years, lost some of its seasonal population to swinging Alacati, which tends to attract young people.

Later on we drove to Izmir, the Greek Smyrna, Turkey's third largest city after Istanbul and Ankara, and its most important harbor on the Aegean. We started out on the hill where Smyrna is thought to have been founded by Alexander the great, king of Macedonia, in the late fourth century BC. A small part of the city was then located on the hill, while the large part was located on the flat terrain near the harbor. Excavations have revealed traces of the city's structures, including the Agora on the hill, where we spent most of our time until closing at 5pm.

The Agora, which served as the administrative, political, judicial and commercial center, covers a rectangular area measuring 120 by 80 meters at the city center. Basements built to eliminate the gradient of the terrain support, by means of arcs, an elevated courtyard covered with stone slabs and surrounded by porticos (columned galleries). A row of Corinthian columns from the ground floor of the western portico has been re-erected. They are accompanied by a double-arched gate; the keystone of the northern arch has a bust of Faustina, wife of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, who restored Smyrna after the earthquake in 178 AD.

The basilica, which served as the business center, is located along the northern side of the Agora. Two floors, built over a basement floor of four galleries, sit on a superstructure supported by arches. The rectangular ground plan is divided into three vertical galleries with rows of columns; the middle gallery is wider and higher than the ones on the sides. Although the complete structure of the basilica and portions of the western and eastern porticoes have been exposed, totally uncovering this ancient site appears to be a monumental task; currently part of it is under a green park. First used in the Hellenistic period, the Agora functioned as a cemetery during the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, as evidenced from the cluster of tombstones on the grounds. The white marble Ottoman headstones feature different turban styles, indicating the rank and profession of the deceased.

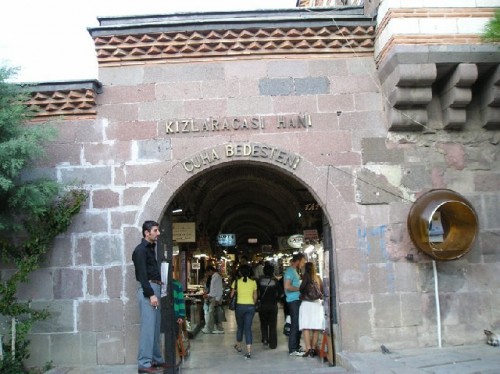

Descending from the hill to the flat terrain, my friends wanted to show me other parts of Izmir. Evin and I walked through the old Jewish quarter to Kizlaragasi Han, an Ottoman commercial structure, where we ambled along a colorful stretch of small jewelry, embroidery and textile shops. We had tea in the courtyard of the Han, and then walked to Kordon, Izmir's attractive seaside promenade, ending with a brief stroll through the mall at the pier, lined with Western luxury shops. Across the way modern apartment buildings with air conditioning units on every floor shared the urban landscape with traditional Ottoman architecture.

For dinner we went to 1888, a restaurant where we met up with some of Evin's friends, also professional guides. They all shared a passion for classical antiquity and met regularly, taking turns to give an in-depth introduction of a topic to the group. That night was an exception, since Evin had guests. Following a variety of cold and warm appetizers, we had cop kuyu kebab, skewered meat cooked slowly in a pit oven and served on a bed of onions with cumin and ground black pepper on the side. Listed in the menu as Aegean-style kebab, this dish was the house specialty. Though usually abstaining from red meat, I break all rules in Turkey, which some consider to have one of the world's top three cuisines. We finished the meal with a sweet made of figs.

Teos was the last Ionian city we visited before my departure. Some of its recently excavated sites include the Hellenic wall and the stage of the main amphitheatre. In the center of the archeological site is the temple of Dionysus, the most famous edifice in Teos. Under the protection of Dionysus, the patron saint of drama, the Artists of Dionysus, the professional guild of actors and musicians who supplied performers for hire at festivals all over the Greek world, enjoyed universal privileges, such as freedom from taxation and military service. Rich in culture, the city became well known as a trading center for fine arts and crafts.

The caretaker of the historic ruins shed light on the very slow process of excavation. Most of the land around is olive orchards, which are privately owned; even if the owner is willing to sell the property, he will not sell the olive trees. There has to be a sustained budget to attract trained people; government funding lasts about two weeks at a time. Archeologists and students working on the digs are tied to the academic calendar and are therefore able to work on site only during the summer, which is also the hottest time of the year. We walked around the temple, which had separate channels for water and wine. Large pieces of stone were connected by iron bars, held in place by poured lead. I wished that the ancient majestic olive tree on the site could recount history.

At the northern part of Teos is Sigacik, a pretty little seaside town with a Genoese fortress from the late thirteenth century dominating the port. Fishermen's boats mingle with private yachts in the harbor. The town's winter population of 17,000 swells to 150,000 during the summer. Old houses in back streets give way to fancy residences up on the hill. We settled at an outdoor family-owned restaurant, where we enjoyed manti, Turkish ravioli eaten with garlic-flavored yogurt.

Evin and Mick drove me to the bus terminal, where I boarded the bus back to Istanbul. As I parted, I thanked my friends for the culturally rich two days I had spent with them. Evin encouraged me to come back to see Sardis, the ancient capital of Lydia, 43 km east of Izmir. I promised I would return!