Patricia Hills: Art World Feminist

A Lively and Insightful Memoir

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 06, 2025

Patricia Hills: Art World Feminist

334 Pages, illustrated with bibliography and notes

Published 2025

Hard Ball Press

ISBN 979-8-9898025-9-3

As the daughter of an Air Force doctor the family was regularly moved and reposted. This entailed disrupted education until Stanford University, 1957, with a major in Modern European Literature. Not long after graduation she married her college sweetheart Fred Hills. While focused on his career she conformed to the role of housewife rearing their first born, Christina. Brad would follow.

While a child of five, as recounted in the fascinating and insightful memoir “Patricia Hills Art World Feminist” experiencing the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It is the first of many intriguing anecdotes and encounters that lace through a lively and provocative narrative.

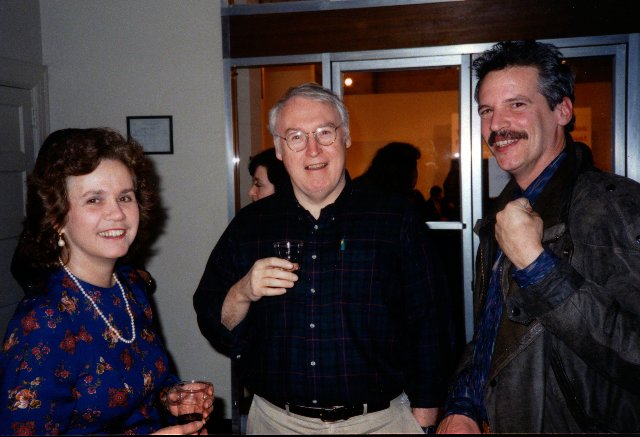

I was a graduate student in American Art and Architecture when I attended her first BU lecture on John Sloan. She was then pregnant with Andy fathered by her second husband, Kevin Whitfield (1933-2021). The presentation was more focused on politics than aesthetics. I asked her opinion of him as an artist.

By then I had completed course work under Dr. Margaret Smith who left for a position at Wake Forest University. She had lured me away from the Italian Renaissance. When I informed my former professor and mentor, Creighton Gilbert, of this change the response was startling. In essence he stated that I was wasting my time and that one Italian artist was more relevant than a hundred Americans.

He was not unique in that scholarly prejudice. It is among the many obstacles that Hills had to overcome. I have known her as a leftist feminist. In difficult increments the book explicates that gradual evolution. We come to empathize with a breast feeding housewife who balanced family and supporting her husband’s literary career while pursuing an M.A. at Hunter College (1968) with Leo Steinberg as advisor and friend. Her thesis topic was "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation."

In 1973 she earned a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Her dissertation, advised by Robert Goldwater, was "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). In 1971-72 she was guest curator for an Eastman Johnson exhibition at the Whitney Museum Art.

With co-author Abigael MacGibeny, in 2021, the National Academy of Design announced the on line publication of the Eastman Johnson Catalogue Raisonné: Drawings & Prints.

She developed secretarial skills in hope of finding an entry level position in a museum. Hills became an assistant to William S. Lieberman director of the Department of Prints of the Museum of Modern Art. It was a project related temporary position. They bonded and he found a way to create an ongoing position for her. Under his guidance she learned all aspects of creating and installing exhibitions. This became invaluable when she later held the position of Adjunct Curator to the Whitney Museum of American Art.

As a graduate student and young curator Lieberman and Steinberg were formidable mentors and friends. There is the amusing tale of how she snuck into the Columbia University lectures of the legendary Meyer Shapiro. His classes were packed and he told those not enrolled to please leave. Pat remained clinging to a ledge at the back of the hall. Later when she casually encountered Shapiro she blurted out how much she had enjoyed his classes. She was outed when he asked in a withering tone if she had been enrolled.

As the narrative evolves we learn of numerous exhibitions, books, and scholarly accomplishments. In e mail exchanges she insists that she wanted to write a memoir not a scholarly book blowing her own horn. With a CV that would choke a horse the accomplishments are too numerous to mention but a few. The thumbnail is that she was among a handful of those who legitimized the study of American art. Her approach to leftist feminism shaped a generation of scholars and curators. She was an activist and administrator for organizations advancing women artists and art historians.

Pat wrote for Art New England and posted reviews for this site, Berkshire Fine Arts, as well as scholarly journals.

She describes later road trips with her husband Kevin in which they visited former students from coast-to-coast. Those who studied and worked with her are passionate loyalists but, as is true in academia, administrative and department politics can be brutal. While university president John Silber was a feared authoritarian he was surprisingly supportive to Hills.

In general academia was not receptive to tenured professors of American art. There was no such concentration at the Institute where she focused on European art. Harvard had a policy of non tenure track, short term appointments. Despite the brief prestige it was an option she would not consider. BU proved to be problematic.

In lieu of tenure Silber offered her a five year appointment as director of the Boston University Art Gallery. With graduate students it was integrated into museum studies training them for the field. Running the gallery was in addition to course work and advising students. She brought a level of professionalism to the program with a mix of nationally known as well as regional contemporary artists.

It was intuitive to focus on artists she was already researching and publishing. I vividly recall shows for Alice Neel and Raphael Soyer. Some administrative eyebrows were raised but Silber supported her. While advocating a liberal agenda she had to walk a fine line. The Boston media responded with blanket coverage. The university reveled in the publicity.

The large gallery is on the ground floor of the fine arts building. With the exception of African American artist, John Wilson, the exhibitions were shunned by the conservative fine arts faculty. Other exceptions included the British John Walker and visiting artists Philip Guston and Alfred Leslie.

Navigating the gauntlet of the BU art history department, for graduate students and non tenured faculty, the knives were out. The book alludes to this but discretely she refrains from finger pointing.

In an interview, however, she told me. “There was a prejudice against me because I was a woman, married, and I had a baby and family. There were women in the department who had given up the idea of having children, or maybe they never wanted children. They didn’t like me. They didn’t like that I was doing American art because that’s so ‘easy.’ It’s not a real art history subject. It was also that I was young and energetic. I would get a bus and take my students to New York to visit museums. Nobody had done stuff like that. I was out pacing them. I was out publishing them. I had a family and I was a Marxist. Someone said ‘You don’t smell right.’ I wasn’t one of them. I wasn’t in their tribe.”

With a lot on her plate at BU she continued to write books and curate exhibitions.

Given her leftist outlook it was surprising the she curated a major exhibition “John Singer Sargent” for the Whitney Museum of American Art that traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1986-87. Critical assessment of Sargent has waxed and waned.

Early on she took studio classes and has an appreciation for the process of fine arts that is not generally shared by her colleagues. She argues for Sargent as one of the great painters of his generation.

As she informed me by e mail, “After the Sargent show, Silber gave me a substantial raise—which had previously been a zero raise from the Provost because of the politics I was bringing to BU Art Gallery exhibitions. He gave me tenure a couple of years earlier when I won a Guggenheim.”

She told me that Silber kept salaries substantially lower than the standard for the field. When she became department chair it was evident that women faculty were paid less than men. She did her best to level that out.

Through it all we learn a lot about her personal life, feelings, and evolving views spelled out in a chapter “Becoming a Radical, 1972.” Followed by “Four Whitney Exhibitions, 1972-74.”

From an art historical perspective the most absorbing and shape changing chapters are devoted to the artists Alice Neel, Jacob Lawrence, and May Stevens.

As an adjunct curator Hills attended the Whitney’s weekly meetings when the director John I. Baur stated that he planned to visit Alice Neel. She asked to join him. He was supportive of her but with the decision to create an exhibition of her work there was an objection as curator. Her position was for 19th century and, as a living artist Neel, was out of her portfolio. But she continued to work with the artist and created Neel’s first full monograph in 1995.

When she presided over her opening and programming at the BU Art Gallery Neel seemed more like Grandma Moses than the potty-mouthed harridan described in the book. Her slide lecture was hilarious. In a nude of her lover Joe Gould he was depicted with multiple penises. She brought down the house with the remark “He was a heck of a guy.” Her radical, expressionist portraits often entailed nudes and pregnant women. In a shocking late self portrait she is brashly nude working at the easel. In somber early works she often painted neighbors in Spanish Harlem.

That she was difficult to work with risks understatement. While she painted a portrait of Kevin and Andy she offered it at a price beyond their means. She never gifted work and the estate was reluctant to make more than a few museum bequests. While not of value during her lifetime today the work is priceless. It was shocking to learn that she even messed with the book. Pat’s former husband, in publishing, suggested that she withhold the book rather then accede to outrageous demands.

After her death at 83, Hills viewed a documentary on the artist. Poignantly she relates weeping. Those closest to us, professional and personal, are not always easy.

As a leftist, Hills has allegiance to the Social Realists of the Great Depression and those depicting racism and repression. We interacted when David and Nancy Sutherland were producing a documentary film on former Boston artist Jack Levine. He and Hyman Bloom were prodigies who were later, with Karl Zerbe, known as Boston Expressionists. After decades of neglect Bloom is now feted by the Museum of Fine Arts which continues to ignore the more political Levine. She told me that when she no longer ran the BU Art Gallery a Levine show was planned. Her successor, however, dropped the ball.

Developing a book on Jacob Lawrence entailed engaging a new and challenging field of study. It is remarkable that a white scholar produced a book on a black artist. Delving ever deeper she had to navigate pitfalls. In this effort she was encouraged by Henry Gates of Harvard who was only interested in the level of scholarship. The superb book, however, did not generate the attention that it would have had from a black author.

The leftist artists May Stevens and her husband artist Rudolf Baranik were among her closest friends and associates. Hills arranged for an exhibition of Baranik’s work at the BU Art Gallery. Later they moved to Santa Fe where Pat and Kevin were regular visitors. Stevens was the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts. The chapter illustrates how professional and personal ties grew and evolved.

The final chapter is personal and heart wrenching. She and Kevin raised Pat’s three children as well as his daughters Mary and Emily. They shared leftist politics and together traveled extensively here and abroad. He was known for cooking when they entertained friends and students. As he succumbed to dementia providing care became ever more challenging.

“When Kevin died at 2 p.m.” she stated “Andy, Emily, Mary and I were by his side. After his last breath Andy blurted out ‘I am so happy that you have died and are now out of your misery.’ I felt the same. A great person- my loving husband- had finally escaped his awful disease.”