The Irish Museum of Modern Art

Dublin’s 17th Century Former Royal Hospital Kilmainham

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 08, 2013

Taking the Abbey Street tram in the center of Dublin for a few stops. From there perhaps a fifteen minute walk up a side street, past a former prison, apartment complex and supermarket, to a wall and gate.

From there a relatively long steep path to arrive at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. At first sight an imposing structure. The former Royal Hospital Kilmainham is described as one of the foremost surviving 17th century buildings in Ireland. It was founded in 1684 by James Butler, Duke of Ormonde and Viceroy to Charles II. The design was inspired by Les Invalides in Paris.

The large rectangular building surrounding a center courtyard was erected to serve wounded and retired soldiers.

In 1990 it was converted as Ireland’s first national institution for modern and contemporary art. The original stables of the Royal Hospital have been restored, extended and converted into artists' studios and the museum runs an artist in residence program.

When we visited this fall the museum had recently been reopened after renovation. Talking with a guard we learned that was more cosmetic than structural. Mainly the lighting system had been upgraded.

Given its former function the complex mostly entails a series of moderately scaled, rectangular rooms containing a nascent permanent collection as well as galleries for special exhibitions. There are no grand galleries or large open spaces. One such is used for lectures and receptions which may indeed be what it was originally designed as.

We found an excellent basement cafeteria which in good weather allows diners to take trays out into the courtyard. The patrons seemed to include a number of young artists some of whom might have been participants in the studio program.

Exploring the permanent collection we were surprised and pleased to find a video work by Michael Snow which was included in Mass MoCA’s survey Oh Canada.

Much of the work we encountered, however, was less familiar.

Prior to our visit to Ireland we had heard much about its strong contemporary art presence. One hoped to find that at IMMA but the space and limits of an emerging collection did not allow for an in depth understanding of trends in contemporary Irish art.

The two special exhibitions opted to present vintage works by women artist with Irish connections. In the main complex there was a retrospective of design, paintings, decorative arts, furniture and woven pieces by Eileen Gray (through January 14). Exiting the main building there was a medium scaled, free standing building which displayed work by the surrealist Leonora Carrington (6 April 1917 – 25 May 2011) a surrealist and novelist (through January 26).

Prior to this encounter Kathleen Eileen Moray Gray (9 August 1878 – 31 October 1976) the Irish born furniture designer and architect was unknown to me. She is likely more familiar to critics of design.

As a young woman Gray divided time between the family properties in Ireland and London’s upscale South Kensington region. She studied at London's Slade School of Art and in Paris at Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi. She studied painting but became interested in design through the Paris expositions. The Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a major influence.

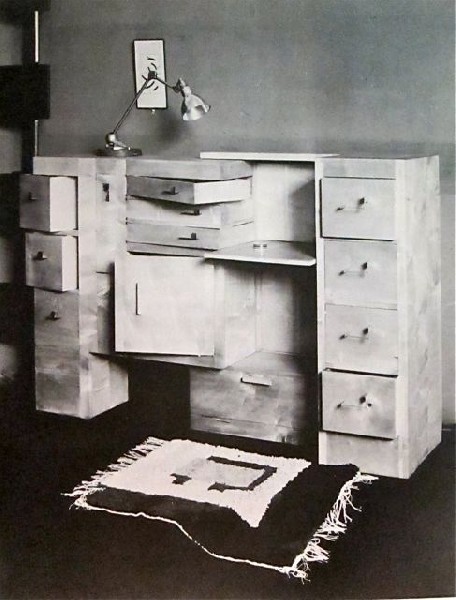

Exploring the exhibit we encountered work in many media and modes primarily aspects of Art Nouveau and later the International School of architecture and design. A casual eye would connect to Bauhaus and the furniture of Marcel Breuer which she compares to in simplicity and the industrial look of materials.

The most iconic piece appears to be her E-1027 table in glass and metal with a round top.

Just a week later, in the lobby of our four star Earl’s Court hotel K & K George, we found an example of that table in the elegant modernist lobby. It was a thrilling encounter and aha moment.

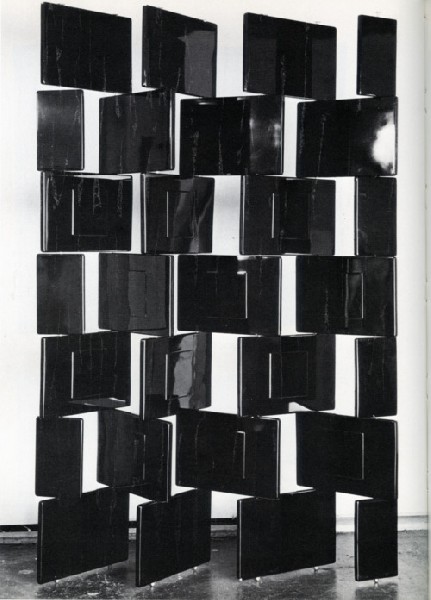

There was much to admire in the range of her work particularly screens assembled from modular, square, lacquered panels. The exhibition demonstrated aspects of working with lacquer which was a favored material of art deco artists and designers.

We were also surprised by her woven rug designs with bold geometric patterns and a simple palette of earth tones.

The broken up ground plan of the small galleries tended to work against a broader and more sweeping dramatic presentation of her remarkable oeuvre. The display broke it down into a series of vignettes of period, genres, and niches of her artistic development. This is an exhibition that one would prefer to see in a grander museum setting.

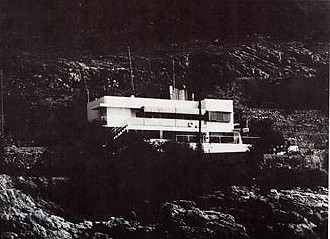

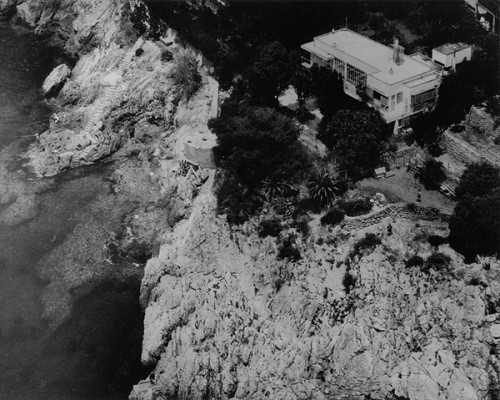

We viewed plans, models and photographs of her architecture. It entailed a limited glimpse of that work. She was active in architecture and design in the 1920s and 1930s building houses for herself and a few others.

During and after the war she resided in France where she became a recluse. Her work was largely forgotten. In 1968, there was a supportive magazine article which revived interest in Gray.

Based on that she agreed to production of her Bibendum chair and E-1027 table (based on house E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in southern France near Monaco which she worked on with Jean Badovici).

Following the purchase of her archive in 2002, the National Museum of Ireland opened a permanent exhibition of her work.

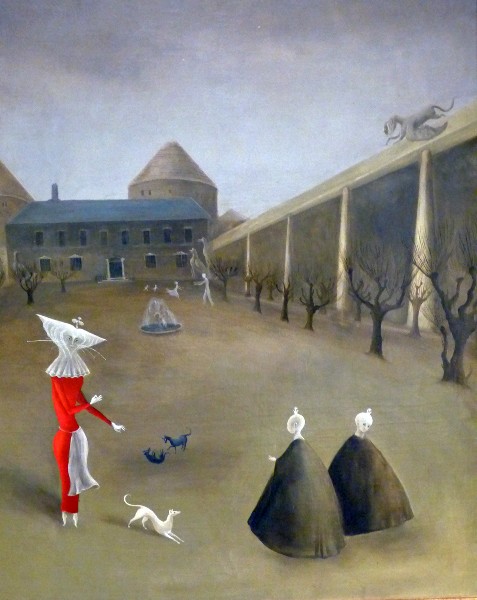

At IMMA this was the most in depth exhibition of work by Leonora Carrington I have encountered. She has been included in survey exhibitions as well as museum collections.

In 1998 we viewed Whitney Chadwick’s Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism and Self-Representation, organized by the MIT List Visual Arts Center.

The exhibition included almost 100 paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures dating from 1928 to 1996 by twenty-two artists from North and Central America, Europe and Japan. From the historic period were images by Claude Cahun, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning and Remedios Varo.

Chadwick has written the standard text for art history courses Women Art and Society. I interviewed her at the Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College when she was working on Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (1985) which includes Carrington. She was a guest lecturer during Carrington’s IMMA exhibition.

The subject of women in surrealism is interesting and complex particularly as it is interwoven with the better known male artists.

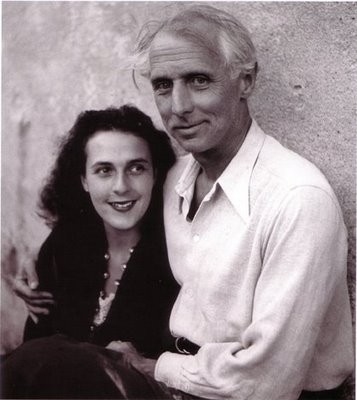

In biographies of collector and gallerist Peggy Guggenheim it is related that Carrington requested a studio visit. Being too busy or disinterested she sent her husband, the surrealist artist, Max Ernst. Bad move as Max left Peggy for Leonora.

Frankly, I don’t have much to say about the work of Carrington which we saw in Dublin. The works were often small to medium in scale and cluttered with small, not very well rendered figures, as in Bosch, acting out complex and somewhat unfathomable narratives.

With more time and motivation one might delve into her iconography. I found the work competent but generally uncompelling. In my opinion she does not hold her own compared to other, better women of the surrealist movement.

That leaves us with second guessing the curatorial motives behind this major treatment of a decidedly minor artist. Perhaps it was the occasion for a Celtic sojourn (consider her Irish mother) presenting yet another interesting artist married to a more famous one.

The museum might have better served its mandate by presenting a cutting edge, emerging, woman artist. That’s what I had hoped to discover when visiting Dublin.

The exhibition of Gray held up, indeed it was revealing, while the Carrington did not. Why relaunch the Irish Museum of Modern Art with a double header of vintage feminism? One? Ok. But two? Not really.

A better programming idea might have been to have one eye on the past and the other on the present and future.