The Weilerstein Trio play Mozart, Shostakovich, Dvorák...and Piazzolla at Williams

A fiery Berkshire evening from a family ensemble

By: Michael Miller - Dec 10, 2006

Weilerstein Piano Trio

Saturday December 9 2006, 8:00 PM

Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Trio VI; Divertimento in B Flat Major, K. 254 (1776), Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Trio No. 2, Op. 67 (1944); Antonin Dvorá¡k (1841-1904) Trio in E Minor, Op.90 "Dumky" (1890-91)

The Weilerstein Trio, Donald, Vivian and Alisa Weilerstein, are a family group, but one which defies any of the usual expectations. They are three strong, highly individual musical personalities who make no attempt to blunt their separate impulses in the interest of a smooth ensemble sound. Together, they give the impression of working as explorers, searching for the most characteristic qualities of the music they play, both through their own understanding and through mutual discussion, either in words or music, in their rehearsals, which must be fascinating for anyone lucky enough to be eavesdropping. On the other hand, I think all of us in the audience were in that position because of the expressive directness of these three remarkable people. Now I'm curious to dig out some recordings of Heifitz, Piatigorsky, and Rubinstein to find out if they projected the same spirit of individuality. I doubt it. People wouldn't have understood it. Since then we have had two generations of Marlboro and all the other surprising vagaries of American musical life.

Many will remember Donald Weilerstein as the first violinist of the great Cleveland Quartet (until 1988, when William Preucil, concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, took his place), which disbanded in 1995. I listened to my lp's of their Brahms Quartets not long ago after a long gap and was thrilled all over again by their penetrating understanding and refined phrasing and balance. It occurred to me today that playing in a trio must allow him a great deal more expressive freedom than the rigors of quartet ensemble ever allowed, particularly in this family situation, where expressive freedom abounds. Mr. Weilerstein enjoys a revered place in history, while his present activity is quite different and extremely lively. As a trio they are in residence at the New England Conservatory, where both Mr. and Mrs. Weilerstein are on the faculty. Alisa, 24, has already gone a good way along a distinguished solo career of her own. Don't forget that she will be playing the Elgar Concerto with Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall in early January!

The concert began with a piece Mozart wrote at the mature age of twenty, published as a divertimento, a light piece intended as background music for a social gathering. This isn't the only work in this genre in which Mozart included subtle shifts of progession and mood, bringing depths to the surface where the "Viennese gentleman" least expected it. The Weilersteins sought out these moments with determination, beginning with an muscular forward pulse set by Vivian and varied with complex rhythmic interactions between all three players, a feat impossible without careful observation of rests and painstaking preparation. In this way their excellence as an ensemble was clear. While the cello lacks a prominent role in this piece, we could appreciate Alisa's full, dark tone, as well as her father's sweeter and and warmer sound. This was a probing interpretation of a piece which could easily be glossed over. No detail was left to waste, and I enjoyed it thoroughly.

Shostakovich's powerful Second Piano Trio of 1944 was for me the high point of the evening. Its dire opening bars immediately brought me into the spirit after five years of war. I was struck by Alisa's attacks in these bars, which were both immediate and strong, but not at all forced. The deep communication among the three musicians enabled them to achieve compelling coordination in a piece in which the composer was expressing an even deeper alienation in the independence of the parts. The Weilersteins made their way through a great variety of moods, tone colors, textures, and dynamics, bringing me back to an unpleasant subject I've mentioned before, the execrable acoustics of the Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall. The louder passages in the Mozart were unpleasant enough, but the considerably greater dynamic range required by Shostakovich left me with the impressions that the musicians simply had nowhere to go, as their sonority built up beyond the point where the human ear shuts off. They brazened it out, however, playing as loud as they felt expression demanded and that worked as well as any solution.

In the second half we heard a richly nuanced, vivid, and VERY LOUD performance of Dvorak's "Dumky" Trio. Again the Weilersteins explored every nook and cranny of Dvorak's varied and colorful invention and made the most of it. Dvorak's expansive cello part gave Alisa a chance to come to the front, and her splendid large tone, confidence in phrasing, intelligence, and charming manner made that one more addition to the rewards of the evening. Their big conception of the score cried out for a larger, more reverberant hall, and there Brooks-Rogers let them down. Williams should really consider using the excellent hall at the Clark, if they are going to invite distinguished musicians to play on campus, or for that matter respect their own outstanding faculty, until they can include an adequate (let's hope outstanding!) recital hall in their endless building program.

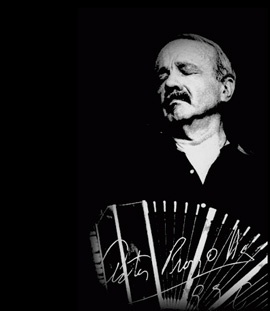

I should mention the encore, a movement from Astor Piazzolla's "Four Seasons of Buenos Aires," in which the family had great fun, Donald working up every bit as much fire as his extraordinary daughter.

The Weilersteins, judging by their new recording for Koch International and their program schedule, make a speciality of Dvorak, which reminds me of my seven years in that under-appreciated but culturally very rich city. The orchestra seems to progress from strength to strength, only of a different sort. You couldn't turn on WCLV without hearing a good bit of Smetana or Dvorak, which, with George Szell's encouragement, became a cultural icon of the city's mixed eastern European heritage. In any case I may have failed to run into the Weilersteins in Russo's Supermarket, but we have met now in Williamstown, and I'm keeping my eye on their concert schedule. These people are research scientists in music, and I know that I'll always learn something new and exciting from them.

* * * * * * * *

Donald Weilerstein has a great reputation as a teacher, as I learned from Joanna Kurkowicz, Williams' own violinist-in-residence, who kindly invited me to his master class Sunday morning. It is humbling to be reminded of what an extremely complex operation it is to play the violin. Mr. Weilerstein referred virtually everything to feeling and the way we express what we feel by singing, whether it is with the voice or by energy proceeding from the diaphragm up the spine to the fingers. Everything can comprise something basic like the way the player stands, holds the instrument, or plays a simple scale, or the deeper meaning of the music the way it tells its story through harmony.

At one point an interesting cultural issue came to mind. Two of Ms. Kurkowicz's very able students, Elizabeth Robie, Hanna Na and Alicia Choi, who played that morning, are Korean. As he worked through the first movement of the Brahms Violin Concerto with Ms. Na, Mr. Weilerstein gently asked her, "Just what nationality is this music...apart from German?" Pause. Silence. "Hungarian," he continued, "Listen to that rhythm." For me this simple observation conjured up the lectures and two concerts devoted to nationality (Hungarian in particular) I had heard at Bard during the summer, as well as a fascinating lecture on exoticism in music ("Evocations of the Middle East in Music from Mozart to Today") given recently at Williams by Ralph Locke, Professor of Musicology at the Eastman School of Music.

National feeling is a quality very deeply connected to the nature of music as in no other form of art, and perhaps it is different for all of us, depending on our cultural background. For example, how did Tchaikovsky's audiences feel the Russianness of his music? How does a Pole respond to the Czech folk elements of the "Dumky" Trio? If one is a student from Korea, what is it to discover the Hungarian rhythms of the music of Brahms, born on the Baltic and transplanted to the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire? Quite different, I imagine, than for a long-term resident of Cleveland, with its important Hungarian population. I find this issue particularly interesting, because, I studied regional and national styles in the visual arts for some years with a professor who later attempted to apply the same heuristic methods to music, with surprising results, since national characteristics play such a different role in the two art forms. In any case I thought this one point made by Mr. Weilerstein was an education in itself and a measure of the profundity of his understanding, as, in the space of half an hour, he magically transformed mere notes into music.