Mamet on Broadway

Hit and Miss

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 10, 2012

It was intended to be a season of triumph for David Mamet who is widely regarded as “America’s Greatest Living Playwright.”

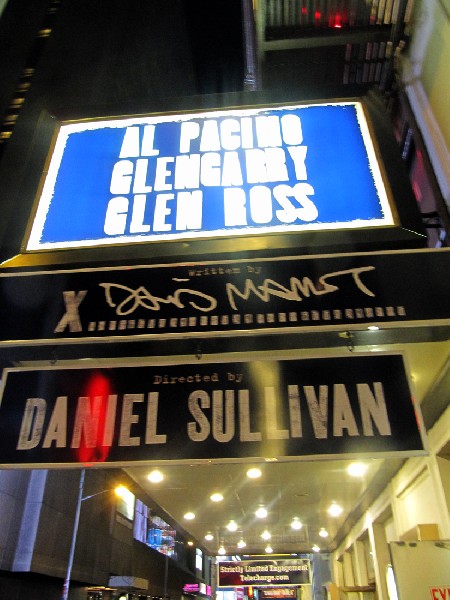

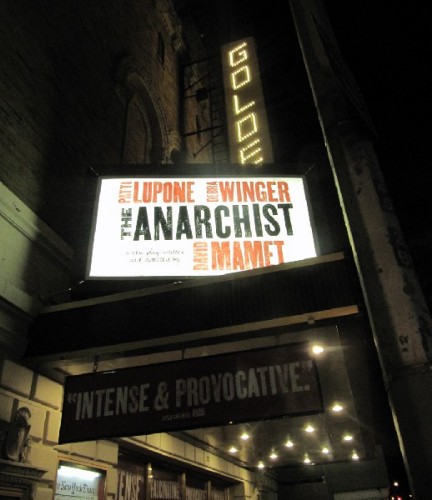

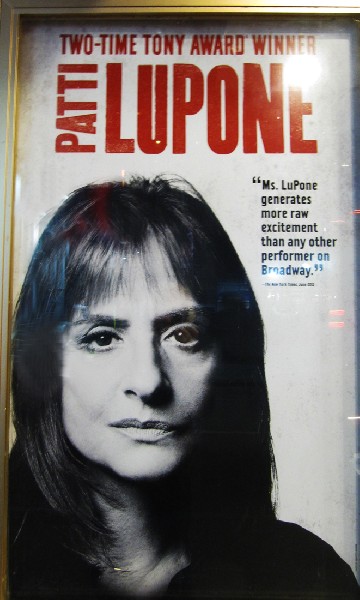

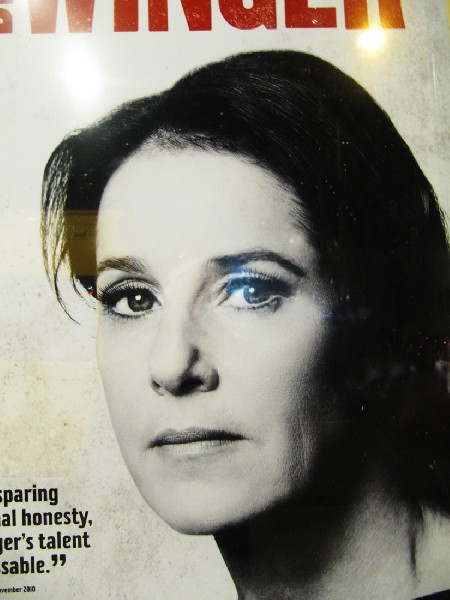

Visiting Broadway last week there were two marquees lit up with Mamet plays on West 45th Street. One touted the revival of the classic “Glengarry Glen Ross” starring the very bankable Al Pacino. The other proclaimed a new work “The Anarchist” with Patti LuPone and Debra Winger.

What should have been an occasion for celebration and triumph has been mired in controversy and defeat. It has cast a dark shadow over a theatrical monument.

Based on the star power of Pacino “Glengarry” had boffo box office sales through the normal three weeks of previews. There was eyebrow raising media coverage about how the previews were extended by another three weeks. The opening last night occurred at the mid point of the run.

There was speculation that by holding off potentially harsh reviews they would not impact sales. It also implied some misgivings on the part of producers that there may be something to hide about this revival.

The power and influence of critics is a subject of debate. Theatre and marketing have changed and the power of critics to make or break shows is viewed as not what it once was.

But that’s exactly what happened just a week previously when “The Anarchist” opened to scathing reviews. Taking a bath, said to be some $2.5 million, producers have pulled the plug on the play which Mamet himself directed.

Having a playwright direct his own work is dicey. Just who has the authority to intervene and suggest cuts, rewrites and changes? Mamet is known to be so fixated on dialogue that he doesn’t appear to have much interest in the nuances of acting. His approach is mostly to have the players stand and deliver his lines.

This is more or less what we experienced with “The Anarchist.” In a story announcing the hasty termination of the show Winger was quoted between the lines about having issues with Mamet’s direction which failed to guide her through the motivation of her character. There was clear evidence of that in her tense and reserved portrayal that revealed few if any emotional insights to her character.

With the new play blown away, indeed cited as the fastest closing of a new work on Broadway by a major playwright in decades, there was anticipation of how the other shoe would drop.

Now the jury is in. In general the reviews for “Glengarry” range from harsh to mixed. In the New York Times Ben Brantley wrote.

“The fight has gone out of the once-robust boys from ‘Glengarry Glen Ross,’ David Mamet’s 1984 Pulitzer Prize-winning drama of sharks in a small pond. Sure, they still curse and rant and beat up on the furniture in the production that formally opened at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theater on Saturday night, after an indecently extended preview period.

“…That sense of defeat has always lurked beneath the speeding dialogue of ‘Glengarry.’ But in Daniel Sullivan’s deflated production, which also stars Bobby Cannavale as the hotshot Ricky Roma, subtext has been dragged to the surface and beached like a rusty submarine. This is a ‘Glengarry’ for a recessionary age. When a character in the first act mutters, ‘It’s cold out there now, John. Money is tight,’ the lines glare in a way they didn’t in the mid-1980s…

“What with the closing notice already posted for Mr. Mamet’s dreary new play ‘The Anarchist,’ which opened last week, this season has not been kind to one of America’s greatest living playwrights. And yes, he still deserves to be thus described. Read ‘Glengarry’ again, and you’ll understand why. Just don’t expect to find the evidence on Broadway this year.”

The bigger they are the harder they fall.

Given the price of Broadway tickets (up to $350 for premium seats for “Glengarry”) it is the mandate of critics to inform potential audiences of what to expect.

Not to say that critics are infallible. Shows that have been praised prove to be duds and, occasionally, plays that open to mixed or poor reviews find their audiences over time.

Given all of the limitations noted by other critics, frankly, I found “The Anarchist” to be absolutely riveting. It was an intense 70 minutes of verbal sparring that demanded complete and meticulous attention.

No, there wasn’t much going on. It was a stark and Spartan set designed by Patrizia von Brandstein depicting an office in a women’s prison. There Cathy (Patti LuPone), who has been incarcerated for murdering two police officers as an ersatz radical Weatherman of the 1960s, is being grilled by Ann (Debra Winger) who is charged with a decision on her parole.

Let us set aside all of the rhetoric about the rise and decline of Mamet and focus on the content of the play. Perhaps it is personal because I have unique connections to the theme of the play. There is also the sense of a kind of assassination of Mamet on the part of critics with hidden agendas as well as chicken shit producers who deprived the play of the opportunity to build an audience.

It is entirely possible that if “The Anarchist” is produced by regional theatres it will find its niche in the canon of late Mamet. On the basis of that intensely intricate dialogue, arguably, he has never been more on his game. It just may take more time to absorb and understand his current state of artistic development.

The Cathy in Mamet’s play seems inspired by Katherine Ann Power (born January 25, 1949) an American ex-convict and long-time fugitive, who, along with her fellow student and accomplice Susan Edith Saxe, was placed on the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1970. The two participated in robberies at a Massachusetts National Guard armory and a bank in Brighton, Massachusetts where Boston police officer Walter Schroeder was shot and killed. Power remained at large for 23 years.

During the 1960s Brandeis University was arguably the most radical college campus in America. Abbie Hoffman was a senior when I was a freshman. I knew Angela Davis through a classmate Evan Stark who was close to her. My lab partner in chemistry, which I flunked, later blew up a NY bank as a Weatherman.

There were many factions on campus. Oddly enough there were materialistic elements that wanted to have fraternities and proms. Some kept kosher and were traditionally orthodox. Others were the mature red diaper babies of their Communist/ Socialist parents.

In the climate of social upheaval and dramatic change of an era of the Vietnam War, Civil Rights, feminism, and nascent gay rights there was a zeitgeist of escalation. There was a challenge of upping the ante and putting the words of Herbert Marcuse, which we heard in the classroom, into action and anarchy.

Founded after World War Two, Brandeis was a haven for black listed professors. Many had endured the ravages of McCarthyism and were not employable by more established universities. So, as a very young institution, Brandeis was able to assemble a formidable and influential faculty with an equally gifted student body.

It is thrilling that Mamet opted to explore deeply into the heart and mind of Cathy.

Everything she so deeply believed in that motivated her anarchy has morphed into the endemic apathy that pervades the current social and political landscape. Significantly, the most compelling current debate is about raising taxes on our wealthiest citizens and tearing down the fragile edifice of government entitlements.

This is weak tea compared to the zeitgeist of the supercharged 1960s during which Cathy gunned down those two police officers.

During the cat and mouse dialogue we learn a lot about Cathy and very little about Ann.

Of course there is a stark difference between drama and a history lesson. For the majority of critics it wasn’t sufficiently entertaining. That Brantley describes it as “dreary” says as much about his political savvy and compassion as it does about Mamet as a playwright. Much of what was revealed was already familiar to me. The fascination revolved around how Mamet set the elements in play.

We learn that Cathy was fluent in French and conversant with its radical philosophy. She was trained in North Africa where she fell under the influence of a charismatic anarchist and sect. She wrote agit-prop pamphlets and produced posters. Some of that work was still in circulation. In prison she wrote a text in French then translated it into English.

When she was arrested the content of her apartment contained incriminating manuscripts and correspondence. Later, through a lawyer, we learn of a fairly recent attempt to contact her on the lam lover and partner. In prison she continued to have lesbian relationships and taunts Ann that she might have any woman she desired and why not?

In prison Cathy was denied access to the literature that motivated her. The readily available text was The Bible which she read fervently. In her tangle with Ann she insists that she has found Christ her savior who forgives her. Her plea for release is based on compassion and mercy. She craves the opportunity to see her dying father and seek his forgiveness.

Asked about her vast inheritance she reveals that she plans to give the money to “the people” which has always been her motivation. If released she plans to join a cloistered order of nuns “because they will accept me.” Ann comments that she would swap one prison for another. Yes, Cathy responds but “one of my choice.”

As the play progresses there is very little inflection or dramatic action. A highpoint entails the very buttoned up Ann removing the jacket of a dark pants suit. It reveals a starched white blouse. Her hair is done up generically and the look is completed with plain glasses. Everything about her persona is taut and impenetrable. She is conveyed as a heartless bureaucrat lacking the depth and humanity to judge a prisoner. By contrast LuPone’s Cathy is more dominant and compelling. This is not to imply that it is a better performance. Rather that Mamet has given her more dramatic latitude in pleading her case. For me, both performances were equally superb. Arguably, the most challenging roles of their careers.

In the give and take Cathy jabs and looks for chinks in Ann’s armor. She probes for ways to read and connect with her. But cautiously, as her fate resides entirely with Ann. The challenge is for Cathy to prove that she is indeed reformed through Christ. That she denounces her radical past and its dire consequences.

There are indications that she may indeed be released. Her cell has been moved to an area where inmates are confined prior to release. Ann is about to retire. She knows Cathy’s case intimately. Perhaps, as Mamet implies, obsessively. She represents the authority and government, the rule of law which, as an anarchist, Cathy did not respect and actively sought to destroy.

Why has Ann taken such an intense and special interest in this one of many cases and inmates? She often quotes from Cathy’s manuscript which she hopes to publish. Ann coldly speculates whether anyone will care. She comments that Cathy and the era she represented has faded from public attention. Cathy is a radical who has been sentenced to live her last days in prison.

In dichotomy to Cathy’s subtle and complex pleas of rehabilitation Ann is charged to represent the families of the slain police officers. Were she to release Cathy her actions would also be subject to intense scrutiny.

While seemingly swayed by Cathy’s arguments Ann demands that she snitch on her lover and accomplice. There was the intercepted correspondence with her lawyer. It implies that she knows how to contact her. Cathy states that she doesn’t know where she is. She asks hasn’t Ann violated Attorney/ Client privilege?

Ann enforces the position that there is no privacy for a convicted cop killer. Anything is fair game. Including confiscating and destroying the manuscript which Cathy hopes to publish (with proceeds going to charity).

In a brilliant response Cathy states that any such action must be reviewed which would mean that the text would be read and evaluated by the prison’s full parole board. Until now it has been read only by Ann.

For all Cathy’s Jesus stuff it ultimately comes down to remorse. How does Cathy now view the act of taking the life of two police officers?

In a fast and stunning exchange Cathy seals her fate by stating “They had guns and should have used them.”

Switching on an intercom Ann asks “Did you catch that?” Then “Take the prisoner back to her cell.”

Although she did not pull the trigger that shot officer Walter Schroeder, when her 23 years on the run ended with arrest in 1993 Power stated “His death was shocking to me, and I have had to examine my conscience and accept any responsibility I have for the event that led to it… The illegal acts I committed arose not from any desire for personal gain but from a deep philosophical and spiritual commitment that if a wrong exists, one must take active steps to stop it, regardless of the consequences to oneself in comfort or security.”

For those of us who were embedded in an era of protest, violence, activism and anarchy Mamet has provided a vehicle to delve deeply into our hearts and minds. For that I am deeply grateful and anticipate an opportunity to see another production of this stridently seminal play.