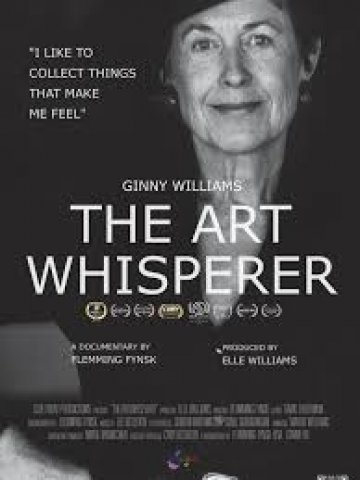

Ginny Williams, Art Whisperer

A Moving Film

By: Susan Hall - Dec 10, 2025

Director Flemming Fynsk's moving film The Art Whisperer is in contention for awards this year. Its subject, Ginny Williams, was an art collector and gallery owner of remarkable instinct and vision.

“Whisperer” has become a common noun in book publishing, a reliable device for leading the path to sales success. The word appears so frequently in titles today that it creates a kind of cacophony. But its origins are quite different. The earliest “whisperer,” was someone trying to keep something quiet—often a rumormonger or slanderer. About twenty years later, the term took on texture: one who speaks softly.

Early in the 19th century, James Sullivan earned the nickname becuase he seemed to communicate his wishes to an animal by whispering.

But modern usage springs from Nicholas Evans’s novel The Horse Whisperer, made popular in a film adaptation starring Robert Redford and Kristin Scott Thomas.

My guess is that Ginny Williams was a woman of extraordinary taste. When asked how she decided what to buy, she said, “I buy what I like. I figure that if I am willing to pay for a painting, someone else will be willing too—if I have to sell. Or want to.”

Williams grew up poor and began her professional life teaching high school English in Cheyenne, Wyoming. She married and soon helped build a business selling log cabins; they were first to the market in that field. When she and her husband separated, Williams had very little money—and she spent what she did have on photographs. She was an excellent photographer herself.

After the divorce, she received enough to begin buying paintings. Her focus was on women. Many women artists who are household names today were virtually unknown when Williams first collected them.

If she were a “whisperer” in the contemporary sense, one might imagine that she cultivated intimate relationships with these artists. But it was the work itself that drew her. She didn’t feel she had to visit their studios before buying a piece. (Many collectors today make such visits a prerequisite—treating art as a social experience, with artists expected to don tuxedos and charm their would-be patrons.)

Williams’s interest in art seems almost pure. She wasn’t looking to make a big financial hit; she bought paintings in order to live with them. And she exhibited her collection so that others could enjoy it too.

Williams lived in Denver for fifty years. One Denverite, a longtime icon at the Tattered Cover bookstore, once passed by Williams’s gallery after closing time and pressed her nose up to the window. Suddenly the door opened, and Williams herself stood there.

“Come in,” she said.

“I saw you were working. I didn’t want to disturb you,” Diane replied.

“I know that,” said Ginny. “I want to show you around.”

They looked at Helen Frankenthaler and Lee Krasner. Then Williams darted away and returned with a poster of Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture The Legs.

“I have something for you,” she said, handing it to Diane. The poster now hangs in Diane’s art collection.

Generosity of spirit, love of art, and kindness—these are the qualities director Flemming Fynsk captures so beautifully in the film.

Not only is this documentary enthralling, it suggests something liberating: if you have good taste, you can afford to follow your heart.

See the film. It’s fun, and it’s inspiring.