Perry T. Rathbone and The Boston Raphael

A Biography by His Daughter Belinda

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 12, 2014

The Boston Raphael

By Belinda Rathbone

336 pages, illustrated, with selected bibliography, notes and index

David R. Godine, publisher, Boston. 2014

ISBN 978-1-56792-522-7

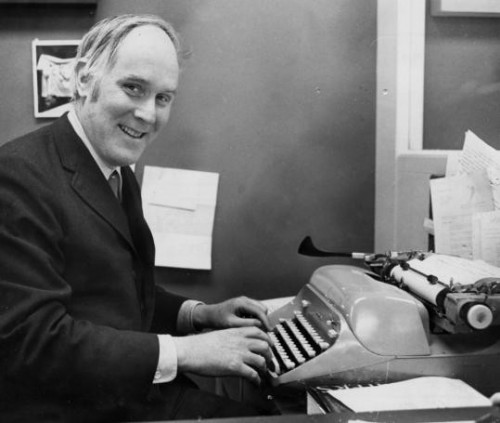

Perry Townsend Rathbone (July 3, 1911 - January 15, 2000) on many levels was the paradigm of a successful and influential American museum director of his generation.

He had a long and remarkable career. Rathbone graduated from Harvard in 1933 and took a year of graduate study. At the height of the Depression he joined the Detroit Art Institute. By 1940 he became the youngest American museum director at the St. Louis Art Museum which was then known as the City Art Museum. From 1943-45 he served in the U.S. Navy in Washington D.C. as head of combat artists, and in New Caledonia as an officer.

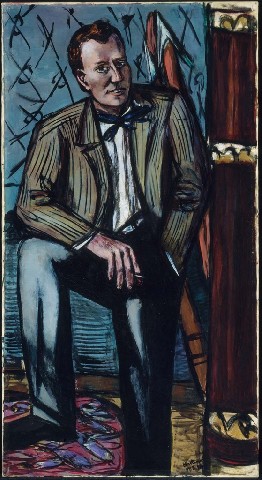

While in St. Louis he enjoyed the support of patrons like Joseph Pulitzer, Jr. an ambitious collector of modern art. Rathbone was instrumental in securing a job in St. Louis for the German expressionist Max Beckmann. The artist painted a portrait of Rathbone which he later donated to the Museum of Fine Arts. He was known for showmanship in promoting special exhibitions.

Partly for that pizazz he was recruited to head the MFA in 1955 with a mandate for change. He followed the stodgy George Harold Edgell who was noted for short work weeks as well as infrequent and brief board meetings. Rathbone was initially hindered by a conservative board of Brahmin Bostonians who resisted change and in particular the modern art which he supported. That gradually changed but at a pace that put the museum forever behind and still playing catchup in the field of modern and contemporary art. The lack of interest on the part of the MFA equated to few significant collectors in a cultured but conservative city.

A brilliant career came to an abrupt halt when Rathbone was caught up in the scandal surrounding the illegal import and acquisition of an alleged early portrait by Raphael. It was intended to be the centerpiece of Centennial celebrations in 1970. Through bungled negotiations that resulted in its return to Italy that led to his forced resignation. Rathbone resigned against the wishes of curators and staff who adored him. They hastily organized a tribute to his acquisitions and guidance The Rathbone Years before he departed in 1972. Women were noted weeping during the opening of that striking exhibition and grand sendoff.

The brilliant and absorbing book by his daughter, the distinguished art historian Belinda, The Boston Raphael, discusses the incident in detail as well as restoring his rightful position based on considerable and unique accomplishments.

When interacting with others Rathbone, an impeccably dressed and well mannered gentleman, had a way of cocking his head at an angle while emitting a smile that easily slid into an endearing laugh.

Why not. For most of his adult life he enjoyed the comfort, privilege and life style shared with the classmates, aristocrats and peers who supported his museum.

One just assumed that he came from old money. Such was hardly the case. His father in upstate New York sold wallpaper and his mother was a nurse. When he failed to earn a scholarship the family struggled during the Great Depression to see him through Harvard.

There he lacked the lineage to make the prestigious finals clubs like the Porcelain; known for its wealthy members who were called the Piggybankers. As a fine arts major, however, he had enough manual dexterity to join The Harvard Lampoon as an illustrator of its magazine. Its members dined together weekly in the most eccentric building in Cambridge.

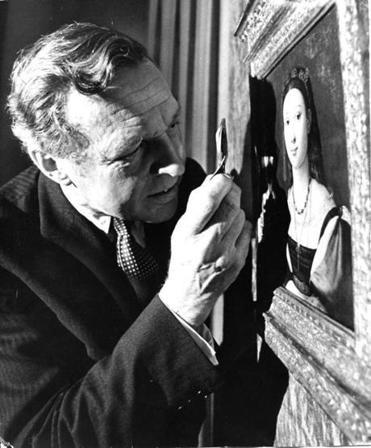

The fine arts training at Harvard was based on connoisseurship and direct involvement with and study of objects. The Fogg Art Museum had a distinguished collection for this hands on approach.

During his undergraduate years the epitome of that training was a museum studies program, later discontinued, taught by Paul Sachs. He was a member of the wealthy financial family of Goldman Sachs. It was a background of power through wealth among New Yorkers. That world and its mores were described by Stephen Birmingham in the seminal book “Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York.”

The approach of Sachs was to conflate the study of art history with all of the challenges of actually running a museum. An aspect of this was how to dress and act properly when interacting with the titled and mega rich. Sachs often invited his museum studies students to join him for elegant black tie dinners. They also visited museums, galleries and the homes of great collectors.

So that natural aristocratic air of Rathbone's was in fact carefully acquired and groomed. It served him well in dealing with the old school trustees of a Brahmin institution like the venerable Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1970, however, because of the Raphael scandal the prestige of the museum was shattered and his career crashed and burned. This downward spiral was accelerated by the President of the Board George Seybolt who was determined to run the museum like a corporation. Seybolt who died at 78 in 1993 was president of the William Underwood food processing company. He was an outsider who wanted in on old money social circles. With some scorn they regarded him as not one of us. He insisted that errant and independent curators keep regular hours. The trustees were expected to attend long mothly meetings and serve on the numerous committes he formed and often chaired. Until Seybolt serving as a trustee was regarded as a droit du seigneur with few if any duties and responsibilities other than rubber stamping with a "hear hear" initiatives of the director.

Until Seybolt there had never been a capital campaign. When an issue came up like fixing the roof or paying for an acquisition the norm was to pass the hat among board members. That also meant that compared to other major museums the MFA had a small endowment and relatively limited acquisition funds. Most of the money to buy works of art was restricted in specific endowments.

That meant that some departments were rich while others were relatively poor. In essence the heads of departments, particularly the well endowed ones, were untouchables presiding over fiefdoms. Much of the success of Rathbone came from diplomacy in presiding over the knights of his round table. His Camelot meant keeping everyone happy.

When Malcolm Rogers became director he ended that division of power under the mantra of One Museum. Departments were merged resulting in laying off and curbing curators.

But pressure from the crass and insecure (as he is described by the author) Seybolt led to an ever widening rift. When the agenda to raise money for the museum was first proposed initially Rathbone and Seybolt made the rounds of potential New York donors. Many of these individuals were business associates of Seybolt. For the Centennial the goal was to raise $20 million.

But it didn’t stop there. Seybolt first asked for a phone, then a desk, an office and staff. Eventually, Seybolt attempted to place himself above Rathbone in the museum’s administration. There were similar developments at the Metropolitan Museum but eventually the Philippe de Montebello (director from 1977-2008) asserted his authority in the chain of command above the business administration. He was one of the last major museum directors to make both aesthetic and business decisions.

While Belinda does a nice job of demonizing Seybolt he represented a trend that was changing the museum field. It became the norm that the director, generally holding a PhD in art history or years as a distinguished curator, was in charge of the collections, acquisitions, appointment of curators and ever increasingly the impetus behind special exhibitions. The term Blockbuster was just emerging.

Fast forward to the present and one may readily identify the fruition of the needs and trends that however crudely Seybolt was mandating. Today, perhaps regretfully, museums are run on a complex business model. It’s all about pulling in crowds, parking, feeding them, herding visitors through blockbuster shows that always end in a shop stocked with publications and souvenirs.

For its Centennial Rathbone planned spectacular special exhibitions including loans from Egypt and Greece. Through a series of complications, including the Raphael incident, these projects were cancelled. A show curated by the Elma Lewis School and Museum's Edmund Barry Gaither African American Artists from New York and Boston was hastily organized to fill a gap in the collection. Gaither was appointed an adjunct curator of the museum.

My first job after graduating with a BA in Fine Arts was working for Rathbone’s MFA. I spent two and a half years working alone in the vast basement storage of the museums department of Egyptian Art. To pass the time I listened to the local soul station WILD just across Huntington Avenue in Roxbury.

One day a guard interrupted my reverie to announce that Mr. Rathbone who was passing by with dignitaries “Requests that you turn down your radio.”

Later as a critic for Boston After Dark/ The Phoenix, and the Boston Herald Traveler I had a more adversarial role in covering Rathbone and the MFA.

As Belinda argues, accurately, her father dramatically changed and modernized the MFA. Particularly in view of what would come later one might contend that while true it was not enough.

It was an era of social and political change. By the 1960s Rathbone was outmoded and old school. When the curator of painting William George Constable retired, with Board approval, Rathbone assumed those duties. Eventually he was spread too thin with two jobs as museum director as well as chief curator. Add to that the additional burden of chief fundraiser and administrator imposed by Seybolt.

Eventually John Walsh was appointed as curator of European painting. During the later administration of former Asiatic curator, Jan Fontein, 19th century masterpieces mysteriously popped up on the walls of the MFA. They were loans from billionaire William I Koch. One of four Koch brothers he collected masterpieces while two others fix American elections. The fourth, Frederick, the only one to attend Yale and not MIT, was the founder of Charleston's Spoleto Festival.

As I reported in the Patriot Ledger their father was a founding member of the John Birch Society. It also emerged that Walsh, while an employee of the MFA, was earning some $25,000 a year to advise Bill Koch on acquisitions. Insiders speculated that Walsh would be the next MFA director. When that didn't happen he left to become director of the Getty Museum in Malibu. Rogers later courted Bill Koch with a special exhibition of an ecclectic and largely mediocre collection. That also entailed displaying his two America's Cup yachts in front of the museum's Huntington Avenue entrance.

The two 'bad' Kochs funded the new, ugly, crass fountains and plazas in front of the Met. Yet again money trumps taste.

For a time Rathbone was able to thrive in partnership with the German born curator of medieval art and sculpture, Hanns Swarzenski. This colorful but eccentric and flawed, mumbling consigliore had unique contacts with European collectors and dealers. Particularly because the museum couldn’t compete in the open market Swarzenski was invaluable in the ability to find stuff.

Like that alleged early portrait by Raphael which a single source, the scholar John Shearman, staked his reputation on stating was original and an image of the youthful Eleanora Gonzaga. The art historian was paid well for his opinion in a tradition that dated back to Bernard Berenson.

In this case the museum would have been wise to seek another opinion. Like that of the distinguished Renaissance scholar Creighton Gilbert my former professor. At the time of the acquisition in an exchange of letters about the painting Gilbert stated that it was heavily restored and not a Raphael. The majority of scholars agree on both points.

But it was the manner of the secretive acquisition and subsequent bungled coverup that brought down the odd couple of Rathbone and Swarzenski which embarrassed Seybolt and the board into volunteering to send the painting back to Italy.

There were tactics and legal strategies that might have readily kept the painting in Boston. Rathbone was traveling in Greece when informed of the drastic action which soon led to a demand for his resignation. In addition to disgrace for alleged smuggling the museum had committed sight unseen to a $600,000 deal. During the Fontein administration the unrestricted acquisition fund was about $1 million. It was later revealed that the dealer, a convicted felon, was hardly fresh to the market. The painting had been offered to a number of museums and collectors with an asking price of $1 million. There were no takers. Prior to Sherman's there had been an earlier but outdated attribution to Raphael.

In hindsight it was all too hanky panky but not inconsistent with how things were done. Belinda, for example, describes an incident when Swarzenski returned from Europe with a large box of chocolates which he passed around to his staff. Then he took the box apart to reveal a little treasure that he had smuggled.

By 1970 Italy had a law that prized works of art could not be exported without exit papers. Like similar laws in England there was a option for the nation and its museums to match or outbid on an “endangered” work of art. That didn’t happen with the Raphael.

Acting as bag man on the caper Swarzenski failed to declare the work when passing through customs in Boston. One of his suitcases contained the painting and another an "original" frame that was later revealed to be a fake. It was a moot point as there was no duty on valuable works of art. It was simply a formality but provided a loophole for an aggressive Italian detective Rodolfo Siviero. After WW II he had been active in recovering for Italy many masterpieces stolen by the Nazis. In this high profile incident he maximized media coverage by going after a prestigious American museum.

The painting now languishing in storage at the Ufizzi Gallery has proven to be of little or no importance. In a poignant manner Belinda initiates this book with an appointment to view the painting which brought down her father’s career.

There are other aspects that make this an interesting and important book. It is the first written on the museum as an institution since the centennial history of Walter Muir Whitehill. Much has happened in the 44 years since then.

Many of the directorships that followed Rathbone’s were mediocre or utter disasters. It was only with Malcolm Rogers, now retiring after 15 dramatic years of expansion and change, that the MFA finally had a director with the skill and charisma that matched Rathbone's.

While researching the book Belinda visited and spent an afternoon with me in the Berkshires. We discussed rather different versions of some of the key events she covers.

She insists that her father brought Modern Art to the MFA. To an extent that’s true. But the point I made is that he derailed what would have been a more productive direction.

Prior to coming to the MFA in 1955 there had been a plan to merge the ICA as a department of contemporary art for the MFA.

Toward that move the ICA relocated from a failed building on Soldier’s Field Road in Brighton to the second floor of the Museum School. After loosing its lease on Newbury Street when Sue Thurman was director the ICA was all but dead and its stuff, including a research library, was stored in the abandoned building which for a time housed the New England Sport Museum.

Like Lazarus the ICA came back from the dead under Drew Hyde with support from Mayor Kevin White as well as Louis and Kathy Kane. The ICA had a gallery in the new Boston City Hall and for a time took over the Parkman House on Beacon Hill. Hyde engineered the move to a former fire station on Boylston Street. After attempts by David Ross and Milena Kalinovska under Jill Medvedow the ICA built its current home on the waterfront

The young ICA director Thomas Messer was doing interesting and ambitious work. As a teenager I saw the first American Egon Schiele show at the Brighton ICA. Messer was “advising” the MFA on acquisitions including seminal works by David Park and Karel Appel.

When Rathbone arrived as a “modernist” the merger with the ICA was scrapped and Messer moved to New York as director of the Guggenheim Museum.

For a time Peggy Guggenheim was flirting with the MFA and other museums. Since the MFA had missed the boat on modern art she was intrigued that her collection might one day fill that gap. She offered the MFA works by her son in law, the surrealist Jean Helion, and other minor works.

Belinda writes that “In 1968 the Guggenheim Museum, directed by Thomas Messer, organized a show of Peggy Guggenheim’s collection, with the MFA among the hosts of its tour. Formerly director of the ICA in Boston, Messer was a friend, or so Rathbone had always thought. When he learned that the show had been abruptly rescheduled, he was quite sure that Messer had deliberately maneuvered Boston out of the tour. So after a decade of careful courtship, there was the writing on the wall. And Rathbone suspected ‘the deft hand of Tom Messer at the switch.’ “

It is also likely that Messer was enjoying a bit of payback for the botched ICA/ MFA merger. Surely it was Perry’s “deft hand” on that switch.

One who was in the room, a distinguished art historian, told me that he was present in Venice when a representative of the MFA made an anti Semitic remark in her presence.

The centennial year that Rathbone planned was intended to bring back the pane et circences that had worked in St. Louis. Instead 1970 left him open and vulnerable for a comedy of errors. In 1971 under organizer Virgina Gunter the museum staged a far out contemporary exhibition Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Elements of Art. During the press conference I asked him when the museum would appoint a contemporary curator.

He was asked the same question by Joan Trachtman, the wife of the artist Arnie, when he spoke before a packed meeting of the newly formed Boston Visual Artists Association (BVAU). Not long after the artists' group The Smart Duckys and friends staged an underground exhibition Flush with the Walls in the men's room of the museum.

Soon after Rathbone called me at the Herald Traveler saying that because of my activism he wanted me to be the first to know (and report) the apointment of Kenworth Moffett as curator of 20th century art. I argued with Belinda that it was the result of pressure from artists. Her version was that it had been in the works as a part of the overall agenda of Seybolt's ad hoc committee's study of changes for the museum. The collector/ dealer Lewis Cabot was key to selecting the formalist Moffett.

Dismissing Messer in 1955 and missing out on the Peggy Guggenheim collection, as well as that of Museum School graduate and MFA trustee, Susan Morse Hilles, resulted in the MFA lagging far behind other major American museums. These mishaps would be followed by other pratfalls.

With Rathbone dispatched Seybolt hand picked his successor a nobody, Merrill Rueppel, who wasn’t even in the initial list of 100 selected by the search committee. Rueppell who managed to alienate just about everyone killed the deal to acquire Pollock’s masterpiece "Lavendar Mist." Soon after it was rejected the seminal painting was acquired by the National Gallery. After just two years of a three year contract Rueppel was forced to resign which also led to the departure of Seybolt.

It caused a crisis with classical curator Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III (August 10, 1925 – November 27, 2008) warming the seat before curator Jan Fontein became first acting then full time director. Former MIT president Howard Johnson replaced Seybolt as board president. Robert Casselman became Fontein's business head and co consul.

Not surprisingly Belinda is biased and defensive in writing about her father. Forced out of the MFA at just 60 he had many academic and museum offers. He joined the dark side as an executive for the British based auction house Christie’s. It was surely awkward for the former museum director to be advising collectors on selling their treasures.

Previously I had read Belinda’s superb biography of the photographer Walker Evans. This book on her father is no less an accomplishment. Her research and scholarship are impeccable. It is likely that no other author would enjoy such insider access to sources. More importantly she was able to weave the facts into compelling and richly humanistic accounts.

For me there was a particular pleasure in reading this book. I knew first hand many of the characters including those who labored in the shadows of the MFA. It was great fun to have them brought back to life. As a critic and reporter I have known and interviewed all of the MFA directors from Perry on. That will probably end with the new guy who replaces Malcolm. I also had fascinating interviews with Seybolt and Howard Johnson. I was surprised when the congenial but arrogant Seybolt also taped our session. Johnson complimented me on being unusually well prepared by asking questions for which I already knew the answers.

Which is saying something for a guy who worked his way up from the museum’s basement. And knows where the bodies are buried.

To be sure today the MFA is bigger and better. Truth is, however, I truly miss the colorful Rathbone years.