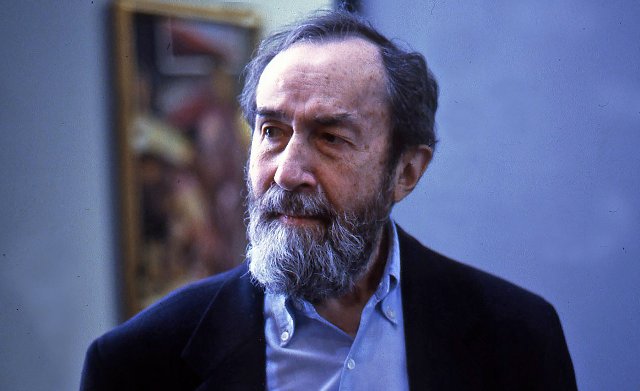

Boston Expressionist Jack Levine

Neglected Colleague of Hyman Bloom

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 12, 2019

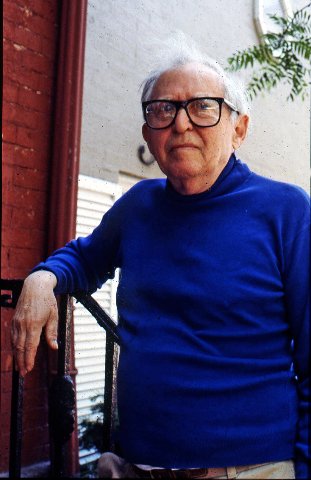

Emerging in the 1930s, with a burst of national attention, The Boston Expressionists were Hyman Bloom (1913-2009) and Jack Levine (1915-2010). They grew up in Boston and shared a unique education.

The third Boston Expressionist was Karl Zerbe (1903-1972). He emigrated from Germany and headed the painting department of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts from 1937 to 1955. He left for a position at Florida State University where he taught until his death.

While a student at the Museum School Harold Zimmerman taught boys at various Jewish Settlement Houses. Of many, his star pupils were Bloom and Levine.

From many of Zimmerman’s students they were tutored by Denman Ross of Harvard University starting in 1929. With no models to work with Zimmerman taught them to draw from memory and imagination. Ross used the boys to work out theories of color and composition.

For a time, Ross, who was wealthy, paid stipends to Zimmerman, Bloom and Levine. He also provided them with a studio. When that ended the boys were barely old enough to join the WPA. Levine’s WPA paintings were shown at MoMA. In 1937 he earned national exposure when “Feast of Pure Reason,” a WPA painting, was acquired by MoMA “on loan from the Federal Government.”

In 1942 Levine was drafted. After serving he moved to New York in 1946 and married Ruth Gikow. Out of sight and out of mind the Museum of Fine Arts, then and now, has shown scant interest in Levine.

Bloom was included in a 1959 MFA group show. Decades later, now through the end of February, it is featuring "Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death" curated by Erica E. Hirshler. The show does not draw attention to his unique relationship with Levine.

The work of Levine has gotten somewhat better attention from the Institute of Contemporary Art. In 1952 it organized a show that traveled for three years ending at the Whitney Museum of American Art. There was a 1979 ICA show “Boston Expressionism: Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe.” The De Cordova museum presented “Expressionism in Boston: 1945-1985.” There was a traveling retrospective of Levine’s work organized by the Jewish Museum in 1978.

Beyond a narrowly focused Bloom show, the MFA is morally obligated to show the whole story of Boston Expressionism. That mandate includes the profound impact on generations of Boston artists. Aspects of figuration and expressionism continue to be lingering signifiers of the art of Boston.

Until the current Bloom show the MFA has passed on creating that narrative, with exhibitions and acquisitions, of major movements and individuals in the Boston Art World. The MFA seemingly lost interest in Boston artists during the 1930s when there was a paradigm shift from Brahmin impressionism to Jewish expressionism. In a broader sense the MFA ignored all Boston artists without regard to race, gender, or creed.

Now under attack for long standing neglect the MFA is obligated to mend its ways. The Bloom show may be regarded as a part of evolving administrative policy.

To be sure this work should be shared by other institutions. The recent ICA has lost interest in creating shows based on art history. For a time, the De Cordova Museum and Danforth Museum took on that responsibility. Those museums are now in states of transition and reassessment.

The Fuller Museum of Art organized a major Bloom show but has now abandoned the fine arts and reinvented itself as The Fuller Craft Museum. The private St. Botolph Club organizes small shows like one last year featuring work by Karl Zerbe.

With area museums in states of flux there is all the greater need for the MFA to fill a need. The Bloom show is a step in the right direction but merely a Band-Aid on a gaping wound of willful neglect.

Through the Lane Collection the MFA has few but representative works by Bloom and Zerbe. It is a scandal that there is no plan to acquire a major painting by Levine. There are major (though rarely shows) Levine works at MoMA, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Brooklyn Museum.

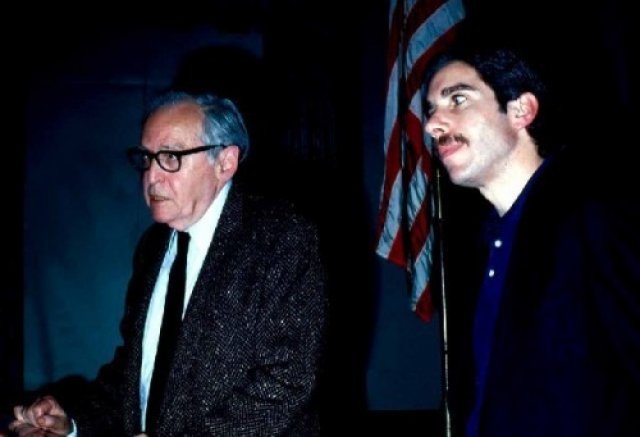

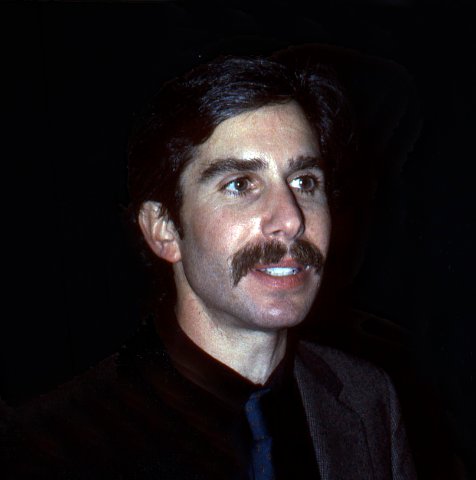

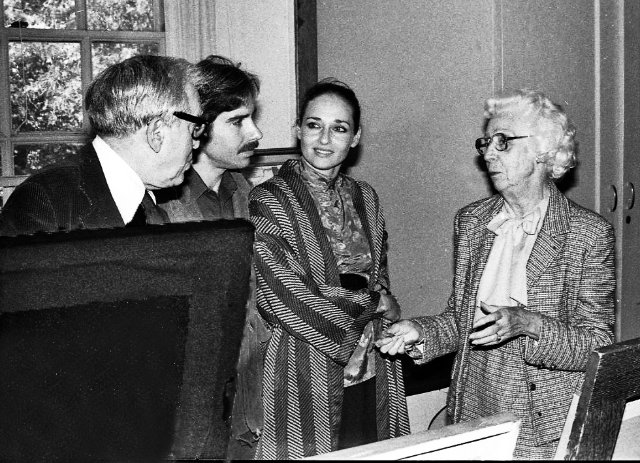

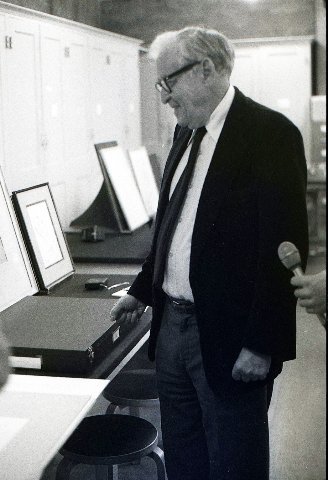

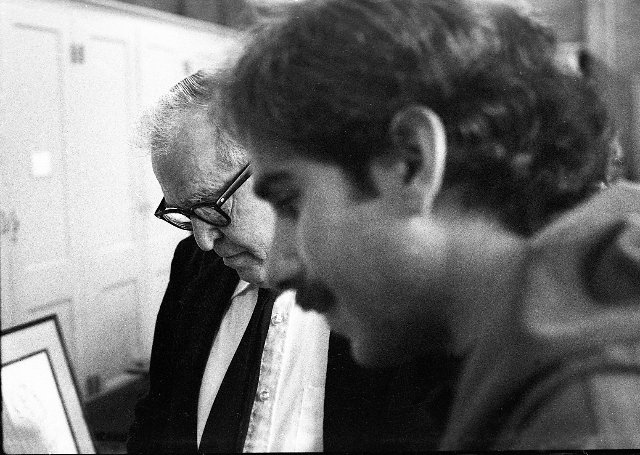

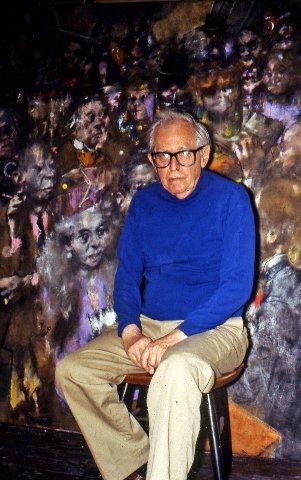

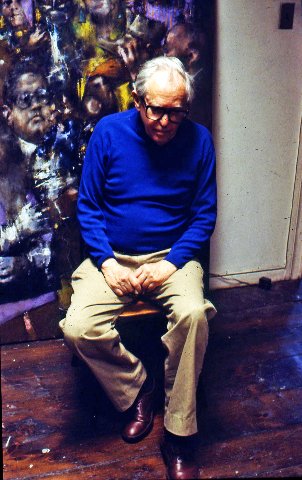

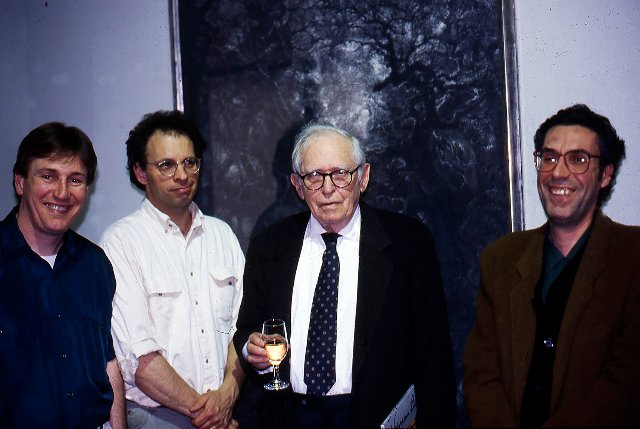

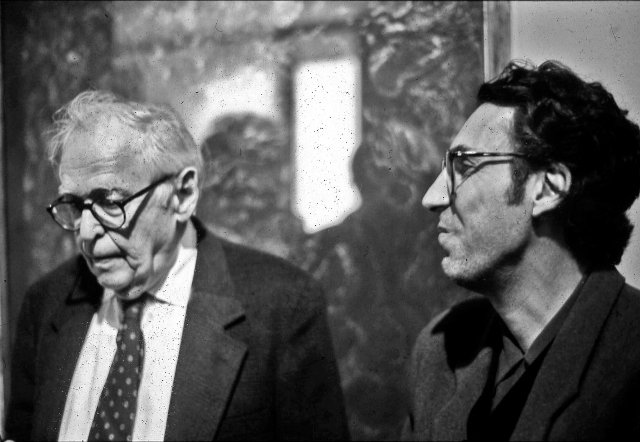

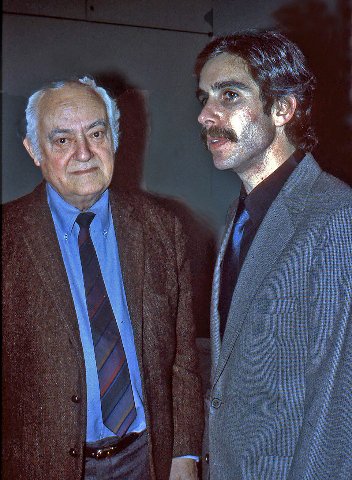

What follows is an interview with Levine. When David and Nancy Sutherland were shooting a documentary film “Feast of Pure Reason” I got to tag along. There were social gatherings, openings, lectures and a visit to see his work at the Fogg Art Museum. We spent a day with him at his New York studio.

Levine did not read reviews or subscribe to art magazines. When asked he refused to discuss demeaning coverage from art critic Hilton Kramer. In general, he had no use for art critics. By the time I turned on a tape recorder he had gotten used to my hanging around. The interview was material for a feature on Levine that I published in Art New England.

Interview April 14, 1986

Charles Giuliano It is the day after the premiere of the David Sutherland film. What did it mean for you? It must have taken a lot of persuasion to get you in front of the camera.

Jack Levine No, because I had seen his Paul Cadmus film. ("Paul Cadmus: Enfant Terrible at 80," 1986). He acquired great status in my eyes. I was recently bereaved (Ruth Gikow, 1915-1982). I looked at the film as a diversion. It filled a gap in my life as I was busy and involved. It’s flattering that they wrote down and filmed everything I said or did.

CG It has taken a year and a half of your life.

JL It has been very important to me. I recently left the Kennedy Gallery, around Christmas time, and what the hell, as I said in the film. I’m slightly less well known and I found that no matter what they said (Kennedy Gallery) they were not interested in projects such as this.

Now I have this film which pleases me very much. Maybe it will expand my universe in ways that fifteen years at the Kennedy Gallery wasn’t.

CG In the past fifteen years, other than a retrospective at the Jewish Museum (1978) beside the Kennedy Gallery you have rarely exhibited.

In the film you discuss a major recent painting of generals, politicians and businessmen involved in the arms race. You comment that the public can’t see the painting because it was sold to a collector in Detroit.

JL That’s right.

CG The public hasn’t seen “Sinatra in Vegas” or “Fanny Fox and Wilbur Mills.” People are unaware of the major works you have created in recent years.

JL “Sinatra” is fairly new so they (Kennedy) hardly had a chance to show it. I can’t fault them on that. But I had a feeling I could do better as far as public image is concerned. Curiously, the money was a matter of indifference because of my age.

(Born in Boston of Lithuanian parents in 1915, Levine was then 71. He was the youngest of eight children.)

I am collecting social security which is handsome. It’s a thousand dollars a month. With a few other things, well, I make twice as much as that before I touch a brush. If I make more money the IRS takes it. I do better if I sell one painting a year than if I sell five. If I make more than that my social security becomes taxable.

CG Do you have printmaking projects?

JL I don’t know of anyone who can handle an edition of a hundred prints. The Kennedy Gallery was asking me to cut down. Art galleries can’t handle so many units. I did two lithographs with Herb Fox and Kennedy talked my out of doing editions of them. That’s all I need, a gallery as an inhibiting factor. I’m trying to find someone to be an outlet for an edition. I’m not interested in doing editions of 15 to 25 prints.

CG Can you describe the stones you worked on with Herb?

JL One was a goofy thing about Tip O’Neill with the Great Seal of Boston behind him. Well, that got scrapped. It wasn’t the best thing I ever did.

CG They still have the stone?

JL No, I assume not. I did another of Adam and Eve and the expulsion but Kennedy didn’t want that either. He talked me out of it. He was trying to talk me down to editions of thirteen and probably selling one (edition) a year. I realize that I’m turning him in and I guess I’m not supposed to do that, but I want you to understand what my situation is, and how it has a bearing on what you asked me. This change of my life.

The film means that for an extended period of time I don’t have to think about shows. That movie is enough of an exhibition to carry me for the next couple of years. That’s the answer to what I was trying to get at. Let the movie do it.

CG The film does that quite well. How satisfied are you with it?

JL Very satisfied. It’s in my own words. There might be some inadversities but I did it myself. I that sense it was a great crew and staff but it was what I said.

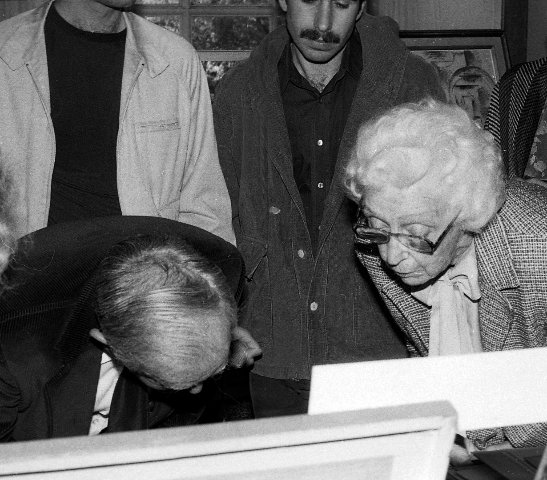

CG David and Nancy Sutherland were very generous in providing access to you and their project. It provided unique insights to your work and process of framing it. I came along during the visit to see your and Hyman Bloom’s early drawings at the Fogg Art Museum. You looked through boxes of work made with Harold Zimmerman and Denman Ross. They were donated by Ross. It is disappointing that this visit and material did not make it into the film.

(A special exhibition of this unique Fogg Art Museum material is long overdue. It provides a one-on-one comparison of two major Boston artists during a moment of their shared development. Some of the Bloom drawings were included in Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death

curated by Erica E. Hirshler for the Museum of Fine Arts. The Fogg’s Levine drawings have never been shown.)

JL Making a film something always has to go but at least I got to see some of the stuff myself. There was one drawing I was relieved to see in the collection “Yakamura on His Death Bed.”

CG He was a servant of Ross who you have described as an aristocrat.

JL For some reason Zimmerman made me copy a photograph of Yakamura and that was substituted for the one I drew from life. But they’re both there (at the Fogg) so I was relieved to see them there.

CG How did you come to study with Zimmerman at the community center? He must have taught many boys.

JL Yes but Hyman and I excelled. There were branches of settlement houses all over town. Hyman was in the West End and I was in Roxbury. I don’t think it paid Zimmerman much but he was going to the Museum School and needed the money. He had kids drawing on manila paper with pencil and that was it.

CG He had you draw from memory and imagination.

JL We were already doing that at the Jewish Settlement House in Roxbury. There I studied Hebrew lettering which they had us draw with arabesques. All sorts of Hebrew letter forms and then paint it with gouache and trace it. There was the imprint of Biblical lore. There was a certain amount of drawing but models were out of the question. Zimmerman developed theories on the basis of what he saw going on. The first drawings I did for him was “Tarzan Coming Back from the Hunt.” That was the first thing I ever did.

CG How did you and Hyman come to the attention of Denman Ross?

(Denman Waldo Ross (1853-1935) was a painter, art collector, and scholar of art history and theory. He was a professor of art at Harvard University and a trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He completed his undergraduate studies at Harvard in 1875, and earned his doctorate in political economy from Harvard five years later. In 1907, he published a manual of design: "A Theory of Pure Design: Harmony, Balance, Rhythm" by Houghton-Mifflin and co. He collected European and Asian art and donated significantly to the MFA.)

JL In a most fortuitous way. I met somebody from the Roxbury branch of the Boston Public Library. He was a con man who was trying to work Ross who was very wealthy. He wanted to see what I had in my drawings books and asked for a couple of sketches to show to Ross. He thought he had something. But I had to show them to Zimmerman so I couldn’t let him have them. I did a couple of sketches on library slips which he took to Ross. Somehow or other I met George Stout.

(George Leslie Stout (1897–1978) was an American art conservation specialist and museum director who founded the first American laboratory for art conservation, as well as the first journal on the subject of art conservation. During WWII, he was a member of the unit devoted to recovering art. They were known as "The Monuments Men.”)

He took me to Ross’s home. I recall that I went to the Fogg and Stout took me to lunch in Harvard Square. Then I told Ross about Zimmerman. Everybody was rejected (other students of Zimmerman) except for me and Hyman. Ross put us on a stipend. (Twelve dollars a week.)

Ross had ideas about systematic impressionism. He wanted to work them out on us. We could draw as damn well as he could. So, it was ready made for him. We were young, malleable and didn’t have to learn fundamentals. He just had to say what color and we knew what to do.

CG I was amazed to see how much of the early work Harvard owns. A lot of people must have given those drawings; Ross, Zimmerman.

JL Zimmerman gave nothing. Paul Sachs over the years bought drawings of Hyman and mine, especially mine.

(Paul Joseph Sachs (November 24, 1878 - February 18, 1965) was an American Investor, businessman and museum director. Sachs served as associate director of the Fogg Art Museum and as a partner in the financial firm Goldman Sachs. He is recognized for having developed one of the earliest museum studies courses in the United States.)

CG Did Agnes Mongan donate drawings?

(Agnes Mongan (January 21, 1905 – September 15, 1996) was a curator and director for Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum.)

JL She may have donated one. It was Sachs (who donated the drawings) and he also bought a small painting of mine.

CG Did you know Sachs and discuss art with him?

JL Not very much.

CG So he was not part of your education?

JL No he was not. He kind of watched over me and I must say, for a man who snubbed anybody, he always bowed low to us. He was all right.

CG (Former NY Times critic and founder of New Criterion) Hilton Kramer wrote an article about you and Hyman “Two Jewish Artists from Boston.”

JL I don’t want to discuss Hilton Kramer. For one thing I think he his political. For another, I think he has an ulterior motive. I think of him as tainted meat and I don’t know why I should say more.

(Hilton Kramer June 1955 Commentary has harsh evaluation of Bloom and Levine https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/on-the-horizon-bloom-and-levine-the-hazards-of-modern-painting/ )

CG Both you and Hyman use Old Testament imagery in your work. Hasn’t that contributed to the negativity and criticism you have both received as exhibiting artists?

(That underscores accusations of anti-Semitism at the Museum of Fine Arts. There was a lapse from 1959 to 2019 when Bloom was featured. In 1959 in a group show and solo in 2019. There are minor works by Levine in the MFA. Unlike Bloom’s, his work has not been the focus of curatorial interest or acquisition. This is a serious lapse given their unique shared education, significance as seminal Boston artists, and status in the history of 20th century American art.)

JL I don’t know what to say to that. I don’t think there is any negative about doing that. What’s worse than anything is having brain-blank when you don’t know what to do until something comes along. I’ll give you an idea of what I mean. One time near the end of my studies with Ross, when I was about 16, he suggested that we could make money by doing postmortem portraits.

It was a horrible idea. There was a professor Kellogg on Brattle Street who had just died. Ross told me to do a portrait of Kellogg in the classical style. He thought that a small painting, framed so it could sit on the grand piano, would be just the thing. He showed it to Mrs. Kellogg and she screamed.

She thought it was horrible. It was taken from a photograph some 20 years prior. He got a more recent photo and had me start all over. It was just like a classical portrait but she couldn’t be bothered anymore.

The point is the project inspired the beginning of my series of miniature paintings. That’s where the format derives. Nothing is accidental. It launched the series of Jewish Kings. It was much easier if you wanted to be influenced by van Eyck or van de Weyden to paint men with beards and turbans or if you’re interested in Mughal and Rajput paintings. You were dealing with something similar. Painting John. D. Rockefeller in tweeds doesn’t inspire but this does. There is the possibility of using gold leaf. As I said in the movie, I came by my use of Hebrew letters honestly.

CG You and Hyman shared an art education but as adults are very different artists. Hyman is poetic and mystical while you are known for social commentary. How did you come to follow such divergent paths?

JL I can’t explain him but I can say a couple of things about myself. I have visited Israel three times. I have a subscription to Biblical Archaeology in which I have become interested. Also, there are certain old left-wing ideas of mine I discovered were not functional as far as Jews were concerned. I thought The Third International (Marxism) might in some way relate to the liberation of the Jew. But it’s practically a prison camp of Jews. I had to disavow a lot of ideas I may have had. Many ideas I had simply don’t work. In a way my involvement with the Jews is political and in a way history mongering. It brings me closer to some kind of artistic precedent I have my eye on.

As to people who say I shouldn’t be involved with gold leaf backgrounds, Hebrew letters, beards and turbans, making hieratic gestures, well the hell with those people.

CG You don’t read art magazines or newspaper art reviews.

JL I haven’t seen an art magazine in possible twenty years.

CG Is it true that you don’t like art critics?

JL Look, I have had no leader since I was sixteen. I have had to figure how to do things on my own. And I am not about to be led. I have done what I wanted for my entire life. I have done whatever my hungry twinges were. If they don’t like it well, I stopped reading them. Then I stopped reading their (critics) successors as I gradually got weaned away from it. Although, I must say, you’re not bad.

CG When there was to be a book you wanted Pete Hamill to write it.

(Pete Hamill (born June 24, 1935) is an American journalist, novelist, essayist, editor and educator.)

JL I sort of know him and my wife thought it would be a wonderful idea. Artists have talked about this. The idea of using a writer who is not an art critic to do the writing for a book. You get a mix of talent and what you get is what you get. Ruth thought that Pete Hamill was a great idea. He was interested but the guy who was going to publish the book went bankrupt. I still like that idea. I want to work with someone who is as much a writer as I am a painter.

CG That describes your relationship with David Sutherland. He is also an artist and not just a documentary filmmaker.

JL Of course that has to be. I have an artist friend who had a show with an essay by Arthur Miller. I liked that.

CG In the past few years there has been a global return to expressionism. (Neo Expressionism). That makes your work seem more contemporary.

JL I would have no way of knowing that. I pretty well lost interest in the expressionists.

CG Because of the film there is interest in your work and the Boston Expressionists. The De Cordova Museum organized “Expressionism in Boston: 1945-1985.” (1986)

JL The film began as a discussion between the man who was going to publish the book and David Sutherland. The film may establish me in a way that hasn’t be true for many years.

CG You have said that you made a big splash in the 1930s and have been progressively less well known since then.

JL Absolutely.

CG Your work is known based on a few images: “Feast of Pure Reason” (MoMA 1936) “Gangster’s Funeral” (Whitney Museum 1952-1953) “Welcome Home” (Brooklyn Museum 1946) and “String Quartet” (Metropolitan Museum of Art 1937).

(From 1935 to 1940, he was employed intermittently by the Works Progress Administration. His WPA paintings, “Card Game “(1933) and “Brain Trust” (1935), were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936. The following year, he achieved national recognition with “The Feast of Pure Reason” (1937), which entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.)

JL The museums that own those paintings keep them in storage. If the Whitney displayed “Gangster’s Funeral” more people would know of me. I know of people who have gone to the Whitney and demanded to see it. Museums are only interested in what’s currently fashionable.

CG How did the Whitney acquire that painting?

JL They bought it fair and square. The director John I. H. Baur was sympathetic to what I was doing at the time. I did that around 1950. They bought it fair and square but later directors were involved with the ephemera of the latest trends. They feel that’s the way they are going to make it.

CG What became of paintings you gave to the W.P.A.?

JL There are two in MoMA “Feast of Pure Reason” and “The Street” which is a big, overdrawn, expressionist kind of thing.

CG So MoMA didn’t pay for “Feast of Pure Reason.”

JL Or they got it as a hundred year lease from the government. I think it says on the frame “Property of the U.S. Government.” I said in the movie that they got two from me. And the third one (“The Passing Scene” 1941). I asked $475 for it and they offered me $250. I said no dice and held out for my price.

CG How often did you have to give them work to get your check?

JL It didn’t depend on how often. They were very liberal. The W.P.A. had two programs. One was the art project and one was the relief project. The art project was very proud of me. I had become well known for being in a show at Duncan Phillips (Museum in Washington, D.C.) and a show at MoMA. I was really their darling. On the other hand, the welfare office fired me because I was living with my family. I wasn’t yet 21. They had me down as part of my family unit. To qualify for relief, you had to be in rough shape.

CG When you were shut off how did you survive?

JL My mother gave me spending money for carfare and cigarettes. That’s how I managed. There was a family coop. Whoever worked and made money gave it to her which she distributed.

CG In 1946 you moved to New York. How were you supporting yourself?

JL There was my Army money and some to a dependent that my mother got. Before I was mustered out, I knew I had a Guggenheim fellowship. A renewal of it. I got a grant from Arts and Letters which was about $2000. The Downtown Gallery sold a lot of my paintings while I was in the service for three and a half years. So, in 1946 I lived for two years on that money. When the prize money ran out, I had a small income from teaching.

CG Ben Shahn (1898-1969) was older but Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was your contemporary. What was your association with the social realist artists?

JL None.

CG You arrived in NY in the mid-1940s well after the peak of social realism during the Depression.

JL As I told you I already had “String Quartet” in the Met so I had arrived before I moved to NY. Did you know that Ben Shahn. Jacob Lawrence and I were part of the Downtown Gallery? There were others like Charles Sheeler, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Stuart Davis. There were some younger artists like Mitchell Sipporin (my teacher at Brandeis University who invited Levine as a visiting artist) and David Friedenthal.

(Legendary gallerist Edith Halpert (1900-1970) established The Downtown Gallery in Greenwhich Village in 1926.)

We had dinner parties and were close in that sense. Shahn was of an older generation and we never visited his farm in New Jersey. We were with the same gallery which is where we would see each other.

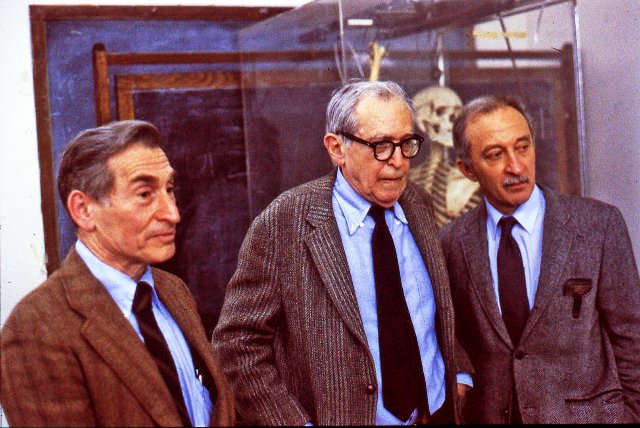

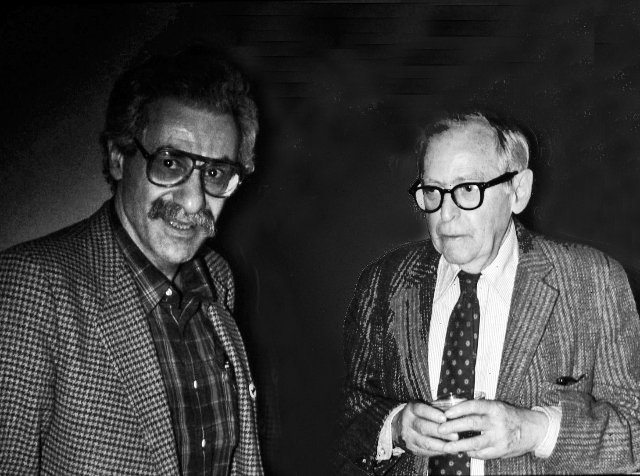

CG What about Raphael Soyer (1899-1987) who came to your opening this weekend?

JL Raphael Soyer is different. He is involved with and curious about younger artists.

CG There is a wonderful portrait he did of you.

JL Yes. He and his brother Moses were like an extended family to me. If Soyer had a show I wouldn’t dream of not going. He was like an uncle to me.

CG Did you enjoy his retrospective at Cooper Union?

JL Very much so. He’s still barreling along.

CG David Sutherland commented to me that he thinks you are now doing the best work of your career.

JL It would be nice to think so. You always compete with yourself. I know that I do. As far as material is concerned, I’m like Elijah and the Ravens. I don’t know what’s coming next. I am working on a painting about the auction houses Sotheby’s and Christie’s. I want to say something about the rotten art world.

In the Sinatra painting (“Sinatra in Vegas”) I was trying to do beauty in the marketplace. I did the carnival and a small painting “Eye of the Beholder.” They are all possible warmups for a big painting about auctions but I’m not starting it yet. I’s still working on “Saul and David.”

CG You’ve been at that for a year now.

JL If you lie back the ideas will come. If you go to work on it that truncates the possibilities.

CG You rework paintings over years. Is it dangerous to have old works around the house?

JL The painting of my daughter is like that. I’ve been painting it for decades. I think I’m now closing in on it.

CG That’s how Rembrandt worked.

JL The guy never finished a painting. People who owned them chained them to their walls so he couldn’t take them home with him.

CG When you see your paintings in museums do you wish you have paint and brushes with you?

JL Well, I see terrible things. It would be like finding a typographical error in one of your articles or a mistake of grammar. That happens to anybody.

CG In the film you say that “String Quartet” is to your work what “Bolero” was for Ravel.

JL It was also about (Leonard) Boucour (1910-1993 an artist who manufactured artist’s colors) who was bugging me in the film. He always introduced me to people by saying how famous that painting was. That always embarrassed me.

That was my only brush with hype but it was the fault of the Met. They put it on billboards in the NY transit system. It was plastered on the side of busses.

I’m more retiring than that but Lennie (Bocour) only is interested in fame and money. He drooled over what a fuss the Met made over that painting. I happen to think that the painting has a lot of flaws.

CG Let’s discuss the flap over your painting “Coming Home.” Did you have to testify before HUAC (House Committee on Unamerican Activities)?

JL I was in Europe at the time. They would have had to pay my fare to testify before them and they opted not to. But they were building up a head of steam. They attacked me because the painting was part of a project sponsored by the State Department. HUAC was interested in the State Department, RCA and MGM.

CG Who owned the painting at the time?

JL The Brooklyn Museum. It was on loan to the State Department but nobody asked me. When May Craig, a journalist from Maine, asked Eisenhower what he thought about my painting he wiped HUAC out of the newspapers. It became a big story. The papers only wanted to write about President Eisenhower’s maiden essay on the art world. HUAC couldn’t get a line in the paper so they dropped it. (Going after Levine)

CG What did you think of Ike as a painter?

(Curiously, Hitler, Ike, and Churchill were painters of which, arguably, Der Fuhrer was the most skilled.)

JL Nobody thought much of Ike as an artist. He did a paint by the numbers image of the golf hero Bobby Jones. You know, it was just therapy.

CG What is your relationship to the MFA and does the museum own your work?

JL Probably they have been given three things by private collectors. (“Street Scene No. 1,” 1936) They’re not very representative works. There are large, major paintings in Chicago, New York and Washington, D.C.

CG In my review (Patriot Ledger) today of the film I remarked that the MFA has failed to recognize you and Hyman Bloom as major Boston artists.

JL That’s absolutely accurate. I don’t know why they never gave Bloom or me the time of day. Do they have a decent (Karl) Zerbe or David Aronson? Do they ever buy? It’s true for any of us and I don’t know why.

CG How do you feel about not being represented in your home town?

JL I can’t come into this town after a long absence and try to peddle this movement. It doesn’t seem politic to raise hell about all that. I don’t know anybody at the museum. I don’t even know their names. I went as far as W.G. Constable (1887-1976) who was the last MFA curator I knew. He was very kindly. If he had lasted longer, and I hadn’t gotten drafted, he might have done something. He showed me the Rubens and that great Canaletto. He was very friendly.

CG The Institute of Contemporary Art was founded in 1936. That was before you were drafted. Did you have any contact with the ICA?

JL Yes. I did a presentation print for them around 1942. I did it on stone and Joseph Butera printed it. I never saw a print of the image because I was in the Army by nightfall.

CG Was there modern art in Boston when you were growing up?

JL There was always modern art in Boston. There were people coming back from Paris doing cubism.

CG What about Karl Knaths?

(The Provincetown artist absorbed cubism indirectly from Maud Hunt Squire, Ethel Mars, his sister-in-law Agnes Weinrich, and Blanche Lazzell.

JL Knaths was a strong painter. I knew him. We weren’t close friends but I knew him when we used to go to Provincetown.

CG Did you know Edwin Dickinson there?

JL I knew him in New York but Edwin not his brother Sidney. We were sort of friendly with Knaths who was a jovial fellow and a very good painter. I don’t think that modern art started in Boston at any particular date.

CG What about (Frank Weston) Benson, (Edmund C.) Tarbell and the Boston Impressionists? Were they still around when you were growing up?

JL Not really. They died when I was young.

CG What about the Copley Society and Guild of Boston Artists? Did you have any contact with them?

JL I didn’t mix with it. There was the Boston Art Club, Doll and Richards, Vose Gallery, stuff like that, (Denman) Ross didn’t approve of all of those people. They were conservative but without any sense of orthodoxy,

CG The ICA later gave you a traveling one man show.

JL That may have been the one that originated at the Whitney Museum. I had a show at the De Cordova Museum, the ICA, and Boris Mirski Gallery.

(The ICA organized a retrospective in 1952. It traveled for three years ending at the Whitney Museum. Under director Stephen Prokopoff there was a show “Boston Expressionism: Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe” in 1979 at the ICA. In 1978 The Jewish Museum organized a traveling Levine show.)

CG Was there only one show at Mirski?

JL I was not in his group. It was a special thing. I knew Mirski but the show was arranged through Edith Halpert and Downtown Gallery. She had a deal with Mirski.

CG What involvement do you have with the upcoming summer show at the De Cordova Museum?

JL I got a letter from them about their use of the David Sutherland film about Hyman and me.

(Outtakes were screened during the exhibition “Expressionism in Boston: 1940-1985.”)

But I’m not a confirmed expressionist. I’m about as expressionist as Rembrandt which is expressionist enough as far as I’m concerned.

CG But you are known as a Boston Expressionist.

JL Especially in ancient times. That was pre war or slightly post war. In other words, I’m not deeply involved with my own subjectivity.

CG Is it true that the film project brought you and Hyman together after many years?

JL It was Stella Bloom, Hyman’s wife, who brought us together. We were very off hand about keeping together. We probably never would have met again were it not for Stella, which is ridiculous. We’ve got a lot of warmth for each other. Stella did it.

CG What has it been like for the two of you to be together again?

JL It’s like brothers. Practically everything that’s involved with siblings: Admiration, pride, envy, all of them.

CG Over the years have you been competing with each other?

JL No.

CG During your lecture today (Boston University School of Fine Arts) you were asked to mention a living artist who you admire. You hesitated and were backed into a corner until you mentioned Hyman.

JL He’s my only colleague. You have to see that. He’s the only one I studied with. When things broke up with Ross we used to meet at the museum and art department of the BPL. We met at cafeterias around Copley Square. There’s a closeness you never get over.

CG Do you consider yourself to be an alumnus of Harvard?

JL That’s a good question. I don’t know what to make of that. Denman Ross created the art department at Harvard. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was alive when he did. Through Ross Harvard sponsored our studies at the Fogg Art Museum. Possibly that makes me a Harvard man. I would like to be a Harvard man because that means that I can look down on NYU. That’s the only reason why I want to be a Harvard alumnus. I live next to NYU in the Village. I loathe them. I realize that I’m talking very freely, loosely, and perhaps a little stupidly.

CG When a group of us visited the Fogg did it seem strange for you to be in the drawings collection? What was it like seeing those early works by you and Hyman?

JL Yeah, but that’s because it was so long ago. I don’t know when I was last at the Fogg. It’s got to have been 55 years ago.

CG Why did Ross end teaching you and providing a stipend?

JL He lost interest. Ross was very wealthy and everyone was after his money. It’s a like a movie where they are trying to knock out people. Not that I had expectations. That’s not it. There was carnage when he was on his death bed. Museum directors were arriving every day. That’s what they do. Do you realize that? What do you think fund raising is about? They sit in vigils. Everybody knows that.

CG So he died not long after he ceased to tutor you?

JL Not long after although I did call and asked for a letter of recommendation. He said that I had said all kinds of terrible things about him which was not true. I was too young for that.

CG Were it not for Harold Zimmerman and Denman Ross we would not be sitting together today.

JL That’s right. But Ruth Gikow said that it was just a coincidence. I had enough talent and drive to have made it anyway.

CG Do you have regrets about not going to art school?

JL I would have had the chance to meet a lot of pretty girls.

CG In the film you say that you really didn’t want to get married.

JL That doesn’t mean that I didn’t want to bum around. Still in uniform I wound up working in an office in New York. What I wanted to do was take up my career as an artist. I wanted to come back to Boston and possibly take back the studio I had. It was the first time in my life that I had a few bucks in my pocket. But I didn’t want to get married and settle down. I had other ideas some of which I gave up to be back in New York in a week.

CG If there was the possibility of a retrospective in Boston would you be interested?

JL I don’t know. I don’t have an agent anymore. I couldn’t do all the paper work myself. There’s a lot of hauling and shipping involved with getting loans for a show. My records tend to be in bad shape.

CG How much inventory do you have?

JL I have about twenty paintings. They’re all in boxes which is how I got them back from Kennedy Gallery. But I don’t have a great drive to show the work. Right now that’s what the movie is for. That’s supposed to do it.