Gonzo Shine

Roots of the Poetry of Charles Giuliano

By: Robert Henriquez - Dec 13, 2015

“A life examined is a life lived.”

That was the closing line in my essay for Charles Giuliano’s first book of poetry, Shards of a Life (2015). Now the shards have been collected, the fog of forgetfulness is dusted away and the raw honesty of a life and art is in full display. Miraculously Giuliano—a prolific poet by all accounts—has done something extraordinary by publishing his second book of new poetry, Total Gonzo Poems, in the same calendar year. Two publications and two hundred thirty-seven poems so far, make for a nascent anthology.

Once again, the new poems in this ever-growing opus compel us to rethink our engagement with poetry. It is futile to compare him to other poets, hoping to find a defining measure for our common life. That’s because according to his own poetic praxis, resurrecting the various ironies of life can be outrageous fun, which in turn opens the door for him to engage in the blasphemy of serious play. Giuliano, the first gonzo poet of our time, stands to accomplish that with swashbuckling flair. His poetry is direct, brief, and unapologetically in-your-face. It takes courage to blaspheme through one’s art, while seeking the absolute truth in one’s life. He has realized it with great facility and brevity in both volumes. In Giuliano’s case, his poetry and life are true monozygotic twins.

During our frequent angst-ridden musings, he often speaks of the low-hanging fruits on the tree of life. We revisit those easily accessible moments of past disquietude as we hope to feel catharsis in the clarity they bring to the present. We do it often, mulling over the vicissitudes of our time with complete honesty, without complete understanding of their purpose or cause. He takes us closer to the middle boughs of the tree in Total Gonzo Poems, “picking” and “plucking” middle-hanging fruits at various stages of maturity. These are other moments of larger themes in a life that demand a fair amount of thoughtful self-investigation. One might argue that manipulating the present and having unfettered access to the past provide a better pathway to knowledge and understanding. It’s a new way of writing about these existential moments. The interesting thing about his poetry is such effort rewards the reader.

In these poems, Giuliano can be relentless with the fast, syncopated rhythm of his language. He urges us on bebopward, with the stark verses in the poem “Up the River,” “Demanding you press on/Further, deeper/Up the river/Into the cave/Where we meet.” Looking carefully, there are no lurches, pauses, hitches, or dead spots in his language technique. We’re paddling with him upriver, matching our strokes to the brisk rhythm and timing of the words, moving seamlessly from one stroke to the other—the gonzo effect in full throttle. All the while, his intention from the beginning was to herd the reader toward a secret, if not hellish, destination of his choosing—the proverbial heart of darkness, “Exploring the horrific/Unknown/Handful of confidantes/Pleased to be among them.” It’s almost an act of desperation on his part as he declares willfully, “Without mercy/Or remorse.”

At first glance the materials of the poetry seem narcissistic, even boastfully so. Essentially, he disregards the entire safety net afforded to traditional poetry for the sake of brutal honesty. There is scant humility in his work, and yet he often shows deference to his critics, not because they may be right sometimes, but because Giuliano has to try his hardest not to condescend. It is clear that his art is his domain, and he is the absolute master of that domain.

The subject matter in his poetry comes from a variety of occasions and spaces that are themselves a complex geography of places and origins. Genealogy and geography play important roles in the narrative focus of his art. That is why the poems reflect his life with such vivid accuracy. The ancestral poems in “The Nugents of Rockport” series move along the migratory axis at the center of the great narratives of “Fabula America.” The epic crossings over the “mare libertatis” are often presented as triumphant episodes of the European diaspora. These brave souls were abandoning wretched conditions for something much better. In order to make some sense of the questions of his European origin, Giuliano eschews those entrenched shibboleths for a more direct and less jingoistic narrative. He is fully aware that, for the most part, those voyages were voluntary, and not enforced. He is also cognizant of the difficulty of relocating one’s roots to a new world.

Giuliano certainly makes a case for the gonzo style as a shift from traditional modernity to a more dynamic, if not extreme, modernity. With “Ancestors”—the first of “The Nugents of Rockport” poems—he clearly demonstrates that the conception of extreme scenarios is an intrinsic element of the gonzo genre. The poem begins with an elucidation of cause, “Born during but/Emigrated after/The Potato Famine.” Followed by the extreme scenario of a cleverly constructed taxonomy of matrilineal ancestry, complete with names, dates, and places. In the end, with surprising effect, the poem strikes a hopeful tone:

Nine formed families

Went forth and multiplied

Populating the world

With democrats

Now with prosperity

Likely some Republicans

Saints preserve us

If Rockport of Cape Ann was the place where scions of the Nugent clan relocated the family roots, Annisquam Harbor is the alternate element for Giuliano’s most engaging materials. He deftly uses them to construct existential moments that present his own artistic process as a composite of thinking and experiencing.

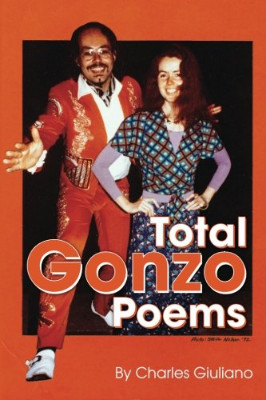

He also shows a great deal of diversity in the Total Gonzo Poems volume by casting a wider net across the contemporary landscape. As a journalist, he is a fast and accurate writer with a keen eye for details, which serves him well when he ventures outside the walls of the familiar. Giuliano is ready and well equipped for his foray into gonzo poetry—with its particular kind of weirdness. Aside from the ancestral theme of this collection, there are other poems filled with his own insight into how he sees the world.“Birth of Gonzo” is a strong narrative of the style that brings home the matter of rightful ownership of the term “gonzo.” There’s a wicked sense of humor and moral indignation in the language he uses in the poem—probably written with both the pen and the sword. The idea of a “proto-gonzo” style emerged from the chrysalis of his literary juvenilia while in college. He later, in 1970, coined the word “gonzo” as an expression and a style. Early on, he plunged wholeheartedly into the hipster lifestyle. Not many of the tragicomic aspects of a privileged youth were lost on him. His image as a boisterous enfant terrible still stands today.

Giuliano is now a published poet, a polymathic iconoclast with an edgy quality about him. Yet he anxiously harbors doubts about the craft and wisdom of his poetry. Also, he is fully aware of the perils of courting the new. Changing the rules of the game begets an assumption of selfishness and arrogance. Critics, bona fide or faux, will show the sharpness of their fangs.

Reading poetry correctly is to hear two voices, the reader’s and that of the poet. It is a synergistic duet played with great effect. Perhaps, with a conscious attempt to attune to this music, we will be able to also hear other voices faintly echoing in our subconscious. These are the voices of memories, near and far, recounting the history of time. The poet writes the words, but the words are theirs.

That is gonzo shine.

For a signed copy of Total Gonzo Poems send a check for $19.95 to Charles Giuliano at P.O. Box 388, Adams, Mass. 01220. Free shipping will be included with orders within the continental United States. The book may also be ordered through Amazon.