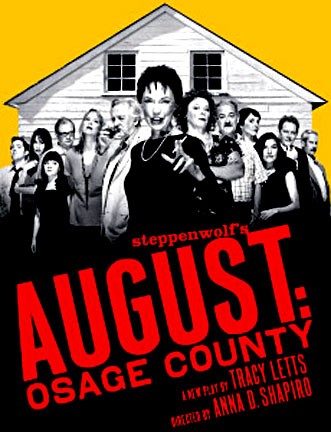

August: Osage County at the Music Box

2008 Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award Winner

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 14, 2008

August: Osage County

By Tracy Letts; Directed by Anna D. Shapiro; Scenic Design, Todd Rosenthall; Costume Design, Ana Kuzmanic; Lighting Design, Ann G. Wrightson; Sound Design, Richard Woodbury; Original Music, David Singer; Dramaturgy, Edward Sobel; Original Casting, Erica Daniels; New York Casting, Stuart Howard, Any Schechter, Paul Hardt; Fight Choreographer, Chuck Coyle; Dialect Coach, Chuck Coyle; Production Stage Manager, Jane Grey; Press Representative, Jeffrey Richards Associates.

Cast: John Cullum (Beverly Weston), Estelle Parsons (Violet Weston), Johanna Day (Barbara Fordham), Frank Wood (Bill Fordham), Madeline Martin (Jean Fordham), Dee Pelletier (Ivy Weston), Amy Warren (Karen Weston), Molly Regan (Mattie Fae Aiken), Robert Foxworth (Charlie Aiken), Michael Milligan (Little Charlie), Samantha Ross (Johanna Monevata), Brian Kerwin (Steve Heidebrecht), Scott Jaeck (Sheriff Deon Gilbeau).

The Music Box, 239 West 45th Street, New York City, 10036, 212 239 6200

Also: The National Theatre, London. US Tour begins July 24, 2009 at the Buell Theatre in Denver, Colorado. The play premiered on June 28, 2007 with the Steppenwolf Theatre Company, in Chicago, Illinois.

As "August: Osage County" begins we contemplate a modest house on three levels including a pitch roofed, attic room and an extending veranda. By slicing away the outer wall the set designer, Todd Rosenthal, has allowed us to look into the cubicles of his doll's house with the characters and actions accordingly encapsulated. It provides a visual short hand for tracking and sorting the large cast of interconnected, family members who brawl and sprawl through more than three hours of a tense, riveting, and often hilarious, dark drama/ comedy.

The pace of the evening begins in a slow and disarming manner as Beverly Weston (John Cullum), a failed poet and alcoholic now in his late 60s, rather charmingly engages the beautiful young Native American girl, Johanna Monevata (Samantha Ross). They are discussing poetry and he presents to her, from messy stacks of books that surround his desk and study area, a volume of poems by his favorite, T.S. Eliot. We assume that she is his student. Indeed he was a professor but it appears not a very good or dedicated one. After a single publication of his poetry, in the 1960s, his career and personal life slid into oblivion.

While we learn little initially about what caused him to be untracked it resulted in a pact with his wife Violet (Estelle Parsons). The deal allowed him to drink with impunity, a point made emphatic as he knocks back the bourbon, while she self medicates with an assortment of pain killers and barbiturates. It is their mutual anesthesia that allows them to cope with the terrible secret that will be revealed in the third act. They have been stumbling and bumbling with each other for several terrible decades. Along the way they did an awful job of raising three daughters.

The man conversing with Johanna is charming and seemingly whimsical about his horrific life. His intention is to hire Johanna as a cook and attendant for Violet who is no longer capable of looking after herself. Beverly is concerned that Johanna may be over qualified and not interested in the job. He knew and liked her father, bought watermelons from him, but it seems he passed on along with her mother. A lack of funds caused her to drop out of junior college and a potential degree in nursing. As she explains to him "I need the work." It will be her modest and sincere refrain as she takes more and more abuse, including racist slurs about the "Indian in the Attic," as the play evolves.

Johanna will be a rock and metaphor that weaves through the play. During the intense heat of August the shrewish elder daughter Barbara Fordham (Johanna Day) will wonder why the original settlers of this "God forsaken place" bothered to steal the land from the Indians. Johanna's constancy, poverty and restrain become a metaphor for Rousseau's "Noble Savage" and a symbol of survival under the most gruesome circumstances. She represents a spiritual and moral plateau that the characters will perhaps evolve to through their own ordeals and ersatz vision quests. Though a servant and minor character in the drama she holds the higher moral ground. The opening dialogue with Beverly is poignant because it tenderly reveals the poet and what might have been.

Just as we become interested in Beverly he is gone after the first scene. Five days later he is still missing. The family gathers in crisis. After a too long delay, which becomes a part of the plot, Violet reports him as missing. Eventually, the Sheriff (Scott Jaeck) and old date of Barbara, arrives and announces that he has drowned. It seems the fish have eaten his eyes. The family gathering morphs into a wake and then a funeral.

The men in the family, such as Beverly's brother-in –law, Charlie Aiken, attempt warm and anecdotal eulogies. By they are disrupted by Violet who will allow no such fond memory to encroach on her bitter resentment.

What evolves over three acts is a drama about the tension between a paranoid, horrific, drug addict mother shut up in a suffocating home, and her issues with each of the three daughters. Violet also battles with her ditsy, bitchy sister, Mattie Fae Aiken (Molly Regan) the mother of the pathetic Little Charlie (Michael Milligan) the object of her constant ridicule and abuse. There are men that are paired with the women but for the most part they are ineffectual and castrated. The women have the stones in this dysfunctional family. The venom and violence of the destructive Violet is matched only by that of the angry, controlling, and bitter Barbara.

For the sake of the family,. Barbara's estranged husband Bill (Frank Wood), a professor having an affair with a student, has joined them in the vigil/ wake/ funeral. He appears to be a nice guy who meekly defends himself as Barbara constantly tears into him. He is holding on for the sake of their fourteen year old daughter, Jean (Madeline Martin). The teenager is a vegetarian who likes to smoke pot and watch old movies like "Phantom of the Opera."

The middle daughter Ivy Weston, a plain, fortyish spinster, is picked on by Violet who wants her to wear a dress and put on some makeup in the hope of landing a man. It seems she has one, oh my, her "cousin" the sad "Little Charlie" who she hopes to run off with to New York.

The youngest, Karen (Amy Warren), escaped the family and moved to Florida some years ago. After some difficulty she has brought home her dream man, Steve Heidebrecht (Brian Kerwin) who is ten years her senior, divorced three times, and far less than perfect. It seems that he also smokes some killer weed and used it to attempt to get into the pants of the jail bait Jean. But not before he is tuned upside the head with a frying pan by the every vigilant, moral compass, Johanna. Steve is a sleaze but even so Karen with outrageous irony plans to stand by her man.

Through all the squabbles Johanna routinely goes about cooking, cleaning and serving this troubled family. One such sit down dinner devolves into a brawl. It has been fueled by booze and drugs. In a confrontation between Barbara and her mother the daughter, at the end of the second act, proclaims that now she is in control. If she doesn't get off the drugs Violet will be sent away.

The third act promises some resolution. Most of the characters leave in varying states of disarray to carry on with their shattered lives. In a plot development the escape of Little Charlie and Ivy takes a terrible turn which brings us back full circle to the rift between Violet and Beverly. By proclaiming that she is in charge Barbara is now locked into the role of matriarch and care provider. There is fleeting hope of a rekindled relationship with the Sheriff but she quickly recovers from that folly. She is doomed and trapped. But finally liberated in one more violent and devastating conflict with Violet in which she is implicated in the guilt for Beverly's suicide. It is the last straw and the resultant rage frees her from being her mother's keeper.

Just prior to that final conflict, seeing that she planned to remain with her mother, Barbara discussed dismissing Johanna. Why keep a maid when she planned to stay on? It was an extra expense. But the pay is modest and Johanna "needs the work." This decision is also Barbara's salvation. After the final outburst Violet in a sobbing state stumbles into the attic bedroom of Johanna who comforts her. Barbara will pay for this future relationship.

So there is no hope or resolution at the end of this play. It just ends. Which is more like life than theatre. For most family conflicts it just ends. Somebody dies while the living get on with their day to day stuff. At least in the theatre, it happens to other people, and however briefly, we are reminded of our own families. It is always better and more fun when bad things happen to other people. So we left the theatre more agitated than appeased by "August: Osage County." Caveat emptor.