Michelangelo Pistoletto at Luhring Augustine

Mirror Images

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 14, 2008

Michelangelo Pistoletto

Luhring Augustine

531 West 24th Street

NY, NY 10011

212 206 9100

November 15 through December 20, 2008

Http://www.luhringaugustine.com

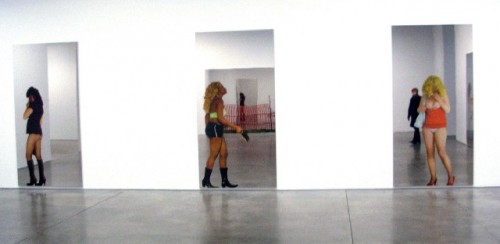

Encountering the mirrored, figurative images of the Italian, Arte Povera artist, Michelangelo Pistoletto (Born, Biella, 1933), for the first time in the 1960s, they seemed fascinating, simple and clever. They entailed life size figures rendered with a deadpan realism on mirrored surfaces. By maneuvering in front of the work, literally, one became a part of the picture. As well as contemplating the ever shifting ambiance of the surrounding gallery.

There is more to the work of the artist than his signature mirror pieces. One of his well known sculptures "Venere degli stracci (Venus of the Rags)" entailed a rear view of a life size, white, classical sculpture which appears to be in the process of being immersed in a mountain of rags. The appropriated and generic, found materials fit the definition of the term Arte Povera which was coined by the Italian curator Germano Celant in 1967. It described the movement of a group of artists who were creating objects using elements of found and industrial materials. It was a more conscious development and extension of the Found Object, Readymade, and Assisted Readymade concepts that Marcel Duchamp developed in the early part of the 20th Century. There was an ironic, anti art, in the traditional sense, Dada prankishness in Duchamp's avant-garde strategy. It was part of his idea that painting was "too retinal."

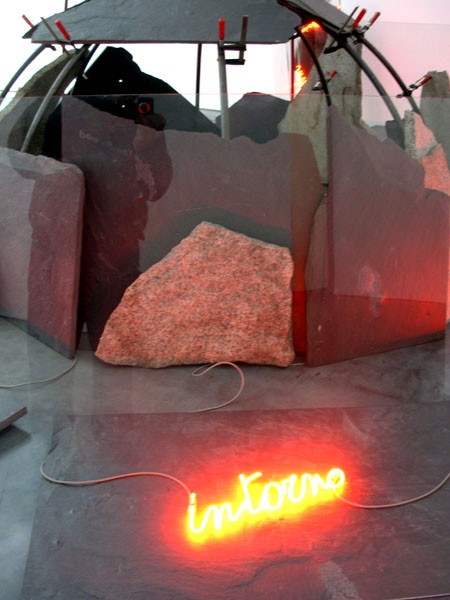

Many artists who have subsequently embraced Duchamp's inventive and whimsical use of materials have not necessarily subscribed to his radical strategies. During our recent tour of Chelsea galleries, for example, we encountered large sculptural works by another Arts Povera artist, Mario Merz (Born, Milan, January 1, 1925 died, November 9, 2003). These were his typical, Igloo pieces, which entail variations of a steel armature into which are inserted such elements as large sheets of stacked glass, slabs of slate and stone, large clamps holding elements together, bundles of sticks, numbers and words written in neon. On the top of one of these sculptures is a life size deer. Variations of works with these materials have been widely encountered in international exhibitions.

This gallery exhibition by the 75 year old Pistoletto is his first major New York exposure in a decade. The absence and return is interesting in that enough time has lapsed to allow for a fresh view of an old idea and to test its longevity. There is also the aspect of a new, younger audience for whom this may be a first exposure.

While the idea was familiar I found delight once again in experiencing the mirror pieces. No, there was not that same, initial sense of discovery, but a return of a sense of play and invention. The pieces also make me recall childhood when walking along Washington Street, in Boston, during the late 1940s and 1950s, when it was movie row. One of the many theatres specialized in screening comedy. We called it the "Laugh Theatre." One of its lures was a set of mirrors that distorted the scale and proportions of viewers. Moving back and forth with screaming delight we found ourselves reflected as giants, fat people, or midgets. Some of the mirrors of Pistoletto have entailed in a modified manner some of those distortions. But that was not the case in the current installation at Luhring Augustine.

Because of the deadpan realism of the figures on the mirrored surfaces, which date to the 1960s, the paintings of Pistoletto are sometimes included in the dialogue about the emergence of Photo Realism as it was developing at that time. This has never seemed right as the images do not entail radical notions of representation so much as a straight up rendering of the figure with an intention to evoke layers of illusion. There is more of a sense of magic and illusion or even shamanism. Pistoletto is more of a conceptual trickster, perhaps true to a source in Duchamp, than a painter of reality.

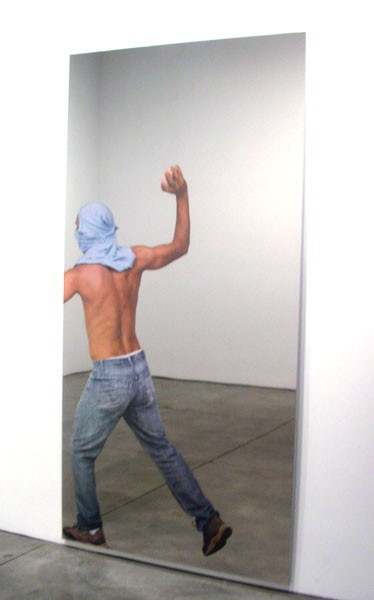

The images on the mirrors are just real enough to lure us in. As we stand before the works they make interesting companions particularly the sexy women teetering on spike heeled boots or crouching in underwear. They encourage erotic fantasies on the part of male viewers. In one work we encounter the profile of a television news camera man. We are welcome to be a part of that event. Or a young man, perhaps a radical protester, hurling a rock during an ersatz demonstration. One side of the gallery entails a very wide work with the bright orange illusion of a fence surrounding a construction site. This work allows for a broad panorama of the surrounding works.

It makes a difference whether the gallery is empty or full of visitors. When the room is vacant the installation becomes quiet and static. But when someone walks through, particularly an attractive, interesting person, the space becomes quite lively as the moving figure bounces off and activates the many reflective surfaces.

So yes, after these many years, the magic and illusion still work. Much time, space, and life experience separates us from those initial encounters decades ago. But there is also that enduring aspect of Homo Ludens which has informed art through the ages. It is the notion of Man the Playful. Hopefully we never loose that sense of whimsy.