Baroque Collection by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

18th Century Music Here and Now

By: Susan Hall - Dec 14, 2011

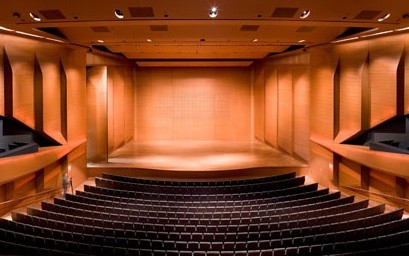

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Alice Tully Hall

December 11, 2011

Kenneth Cooper, harpsichord

Lily Francis, violin

Ida Kavafian, violin

Amy Lee, violin

Jessica Lee, violin

Mark Holloway, viola

Andreas Brantelid, cello

Kurt Muroki, double bass

When Musical America chose David Finckel and Wu Han, artistic directors of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, as ‘musician of the year,’ everyone nodded: Of course. While many institutions which present classical music are wringing their collective hands about keeping this form alive and well with younger generations, Finckel and Han have brought lively, brilliantly performed classical music to halls packed with people of all ages. They have not done this by dumbing down music, but by presenting selections with passion, bravura and especially complete musicality. Unafraid to tackle chamber music in its most sophisticated forms and engage by speaking in musical language that can be understood by wide-ranging audiences, CMS programs are at once intimate, warm and challenging. The Chamber Music Society is a model for institutions struggling for audiences.

These are the not your first thoughts or feelings as you sit down for a concert called Baroque Collection. As part of their December concerts, the program began with the Sinfonia in C Major for Strings and Continuo by Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, J.S. Bach’s second son. It is not hard to see why his contemporaries loved CPE Bach for his daring, turbulent music, which agitates with volcanic harmonies and distinctive rhythms. In its inaugural performance by the CMS, the artistic directors explain that music of the baroque period was not constrained by social mores. Composers competed to astound their audiences and provide enticing repertoire where instruments were often tweaked and modified to surprise listeners accustomed to a different sound. Mark Holloway, violist familiar as a participant in the Boston Chamber Music Society festivals, was outstanding in his warmth and intimacy.

Heinrich von Biber was the most brilliant violinist of his time, and Ida Kavafian took on the wrenching Crucifixion from the Mystery Sonatas he composed. The violin is strung for different effects. The technical difficulty and intensity of this sonata reflects the composer’s wish to display his own technical wizardry. The sonata begins with the hammering of the nails into the cross and continues through a wild, passionate resurrection performed with indescribable intensity by Kavafian. She has been performing with the CMS for decades, but her consummate skill and availability in-the-now bring her music making directly to the heart. Tough stuff to awaken the soul too.

Kenneth Cooper, an 18th century music specialist and director of the Berkshire Bach Ensemble, connected the music throughout the evening on the harpsichord, except for the Concerto by Telemann, which followed his godson’s opener. This piece for four violins was probably created as home entertainment.

Telemann’s Suite based on Don Quixote is charming and also funny. You could almost hear Rocinante’s clopping horse beats. Its light touch provided emotional respite. Yet Kavafian got so carried away that she broke a string and had to exit to have it replaced. Kurt Muroki on the double bass said her string had gotten caught in a windmill. He reported that he never broke a string, because, he grinned: his strings are thicker. Kavafian returned with a shout out to her family in the audience, Dinner is going to be late.

Nothing is inauthentic about these exchanges with the audience, because first and foremost music is being sent out as a gift. The young phenom Andreas Brantelid enchanted in cello solos in the Vivaldi Concerto, and a J.S. Bach Concerto wrapped up the evening with all seven performers turning to each other in acknowledgment, a joyous sharing, and magical music making.

What Finckel and Han do is present music in a language that honors the compositions, but also the spirit in which they came to life. That spirit is translatable to our times. Like Riccardo Muti in Chicago, these musicians make an argument for the centrality of music in our lives. Music is not an ornament. It is not only beautiful, but disturbing and startling. It unsettles with the diversity of its language. A strong case is made for the language of music being taught in schools from Headstart on through high school, to students from all kinds of backgrounds and interests. No one would be better to organize this effort than the Chamber Music Society. Just listen to them in concert, on the radio, in recordings.