Denise Markonish Part One

Mass MoCA Canadian Show Opens May 26

By: Denise Markonish and Charles Giuliano - Dec 15, 2011

Charles Giuliano You have completed some 400 studio visits in Canada. From which you are working with a selection of sixty or so artists which will be shown at Mass MoCA opening in May of 2012.

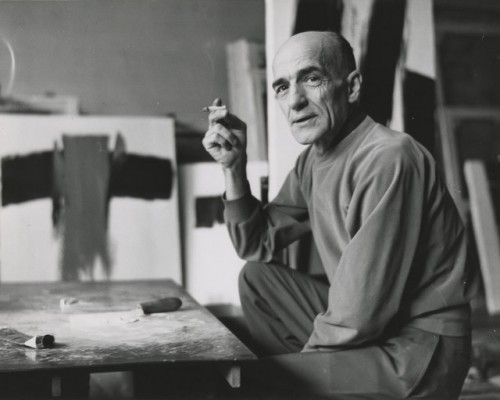

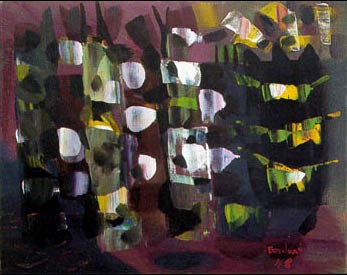

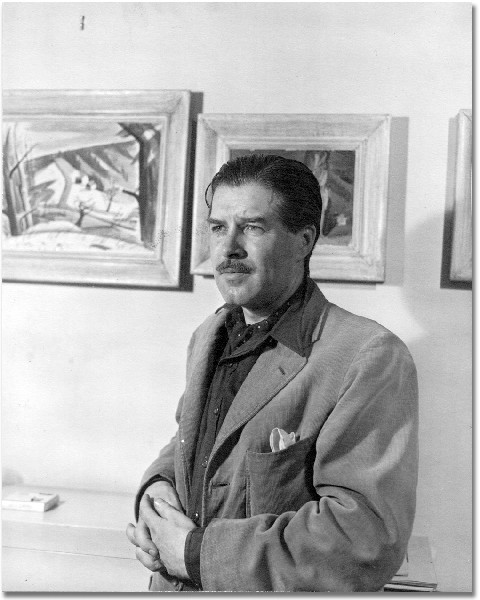

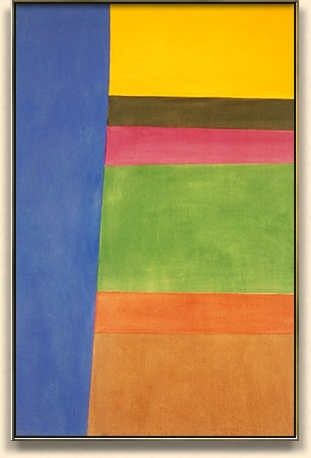

Over a number of years I have made regular trips to Montreal, often at the invitation of the Canadian Government to cover a series of exhibitions and events. There I have become good friends with the gallerist, Rene Blouin, and curator Claude Gosselin and his partner in the Biennale, Pierre Pilotte. So I have an intense interest in contemporary art in Montreal from the generation of the Refus Global to the current generation. The Post War generation included Paul-Emile Borduas, and Jean Paul Riopelle. Later there was the color field painter Jack Bush and the multi media master Michael Snow.

During the 1960s, I worked at the East Hampton Gallery in New York which focused on Op Art. We showed several Canadians; Guido Molinari, Marcel Barbeau, Claude Tousignant and Jacques Hertubise.

Through Rene I got to know and interview Betty Goodwin one of the leading artists of her generation and the much younger Genevieve Cadieux. Jana Sterbak created the famous Meat Dress which Kathy Halbreich showed during her time at the MFA.

Surely through your recent research you will bring to us a whole new generation of artists. This will be a great topic to explore but let’s start with the backstory.

It seems we are both graduates of Brandeis University. I am class of 1963 and you attended at a later time. During my years the Rose Art Museum was founded and I interacted with its first director Sam Hunter. You attended later and took classes with the museum’s director, Carl Belz. Tell us about that experience and explore how Brandeis shaped your understanding of art and later career as a curator.

During my time at Brandeis a number of alumni turned out to be bomb throwers and ultra radicals some of whom ended up on the FBI most wanted list. My chemistry lab partner blew up a bank. I flunked the course. Washed out of Pre Med and ended up with a life in the arts.

Those of my era often feel that Brandeis changed and not for the better. It softened from an ultra radical hot bed to a prestigious but no longer revolutionary university.

Of course a major issue is the still unresolved fate of the Rose Art Museum. As an alumna and museum professional I am sure you have very specific responses to that situation. For me, as an alumnus, it has been like a death in the family. I feel completely betrayed. The Rose was central to my education. My relationship continued for decades when I covered its exhibitions and often interviewed Carl and published reviews. Of course that was going on during a time when the Rose was the leading institution for contemporary art in the Boston area.

The sad history of the Museum of Fine Art in the field of modern and contemporary art is an issue which has been covered in depth by myself, David Bonetti, and Mark Favermann through Berkshire Fine Arts.

So let’s start with Brandeis and how you came to concentrate on art. Who were some of the influential professors? Were you involved in other creative activities? There was a lot of active theatre and music. Did that influence you? Did you take courses with any of those original, leftist professors? Did Brandeis in any way radicalize you?

Denise Markonish Yes the Canada show has definitely been a rather epic undertaking for me over the last 3 years (and a project I started thinking about over four years ago when I interviewed for the job here at MASS MoCA). But we will return to Canada later.

Just the other day I got an email about an interview you posted between yourself and former Rose Art Museum Director Carl Belz. I must say, I was immediately filled with nostalgia (followed by anger at the unfortunate treatment of the arts by the Brandeis administration). Not to discount grad school or other internships, but Carl (and Pam Allara at Brandeis) was the biggest influence in shaping me into the curator I have become.

I did indeed attend Brandeis later than you and I still remember that the first thing I did after dropping my things in my dorm room was to go to the Rose and ask for a job. I had always been an artistic kid, in high school making art myself, but also very intrigued by the inner workings of the museum (a school field trip to the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton, MA opened my eyes pretty wide – leading me as a high school senior to declare that I wanted to work in a museum! It is a funny coincidence that some six or seven years later I would wind up as the curator of the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton, Mass). So, back to Brandeis, I clearly remember the staff at the Rose saying that no work study jobs were available at the moment. I told them that I didn’t need to get paid but just wanted to spend my time with the art. Thus began my nearly four years at the Rose (with brief college internships at the Judy Ann Goldman Gallery and the Fuller – but I always came back to the Rose). I started working with the registrar John Rexine, learned some framing from Roger Kizik, and eventually worked in education and curatorial. Basically I was around to help anyone who had a project!

I loved the hands on work, from doing condition reports, serving as a photographer for their education programs, to replacing candles in Ana Mendieta’s piece in the seminal More Than Minimal: Feminism and Abstraction in the 70s exhibition. (Curated by Susan Stoops now with the Worcester Art Museum) But one of the things that was so important to my outlook was the fact that Carl would just sit with me, in the back room, or storage vault and ask me what I thought about art. I remember, even at the time, thinking that this was remarkable, that this museum director cared what I, a 19 year old kid, thought about art. Everyone at that museum treated me with such respect (the same respect they showed the artists they work with, which is something I learned there that I carry with me dearly).

So, in the end, I don’t think it was Brandeis that shaped me into a career in the arts but it was the Rose, which in some strange way, even back then, I saw as its own place, disconnected from the rest of the university. Though I cannot discount the amazing influence my classes and discussions were with Pamela Allara were. Pam was the most amazing champion of the difficult in art, the dangerous, the thrilling. Her in combination with Carl are the reason I decided to do what I do!

I like you felt insulted when I read what Brandeis wanted to do to the Rose (just as I had when Carl was “asked” to leave in the late 90s). However, I wasn’t surprised and that, to me, was the most disappointing feeling. And, more recently, great artists from Boston have been teaching there, folks whose work I have shown like Joe Wardwell and Tory Fair. The imbalance at that university is astounding both as a student and now a museum worker.

Oh and to answer your questions about the radical nature of the university – that was long gone when I got there (I always felt like I would have fit in there as a student in another decade and I often heard stories from my Uncle Robert Szulkin who taught there). But as you can tell from just this early part of my discussion, I spent all my time in the Rose.

CG So it seems that as a curator you bloomed at the Rose. Can you expand on how the influence of Belz and Allara informed your point of view about contemporary art and strategies as a curator? Can we have a time line? When did you graduate from Brandeis and where did you go on to do graduate work? I graduated from Brandeis in 1963, after several years in New York working in galleries, I came back to Boston in 1968. The art world then, in New York and Boston, seemed so much smaller compared to today. There were more defined movements such as Pop, Minimalism, Color Field painting, Earth Works, Conceptualism, Performance Art. That was followed by Pluralism. In the current scene the diversity is so pervasive that we no longer try to create groups and movements.

How did your initiation and training equip you to deal with the ever expanding vastness of the contemporary art field? You mention the Fuller Museum of Art, in Brockton, Mass. which has now reconfigured itself as the Fuller Craft Museum. Didn’t you leave as a result of that process and transition? When it became a craft museum there was no longer a need for a fine arts curator. Discuss what you were doing at the Fuller? What were some of the projects and who were the artists you were working with? After the Fuller you moved on to Connecticut before coming to Mass MoCA, now four years ago. In essence can you give us a summary of the curatorial projects and focus that led to a position with one of the nation’s largest and most prestigious contemporary art museums?

DM I graduated from Brandeis in 1997 (and as I mentioned before, I spent the bulk of my time at the Rose with briefer forays at the Judy Anne Goldman Gallery and The Fuller). I guess you could say I knew what path I wanted to take early on so I went to graduate school straight from Brandeis. I spent the next two years at Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies (early on in the program’s life). While at Bard I did an internship at the ICA in Boston – a tumultuous time for the Museum with Christophe Grunenberg departing that summer. I worked with Shimon Attie, who I recently reconnected with, doing research on the history of the building for a project he would do later that year (1998). I have always had an affinity for representing my home turf, my thesis exhibition at Bard included the work of Mark Winetrout (the much beloved champion of art in Boston at the MASS Cultural Council, who is no longer with us – though the Hessel Museum at Bard bought some of his work from my show, which was recently in a group show there).

One of the main things that I learned in this “education” period was to know the ins and outs of the museum. At the Rose I was very careful to dabble in each department, finding the one that was the best fit for me. I also think the best education any curator can get is to work with registrars and preparators. That way you understand not only how to care for work but what goes into its making and the mounting of an exhibition. To this day I still say that Carl and Pam taught me how to think about art, how to work with artists, and how to be open to everything. But it was John Rexine (registrar at the Rose) and Vinnie Marasa (THE preparator in the Boston area) who taught me the most important nuts and blots. There is a different level of conversation that can happen between an artist and curator if both the realm of ideas and the practicality of making can be understood.

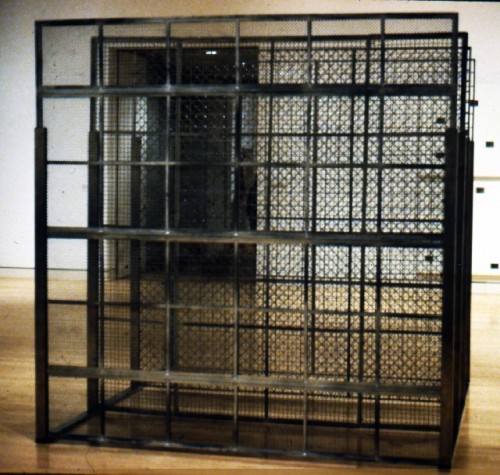

After Bard, I went back home and was visiting the Fuller. Caroline Graboys – the museum’s director – had just passed away and Jennifer Atkinson, who was the curator I interned with, had just been named director. (She is also now deceased.) You could say I walked in at an idea moment and was offered the curator job. The Fuller was an interesting place to get started, this little museum in a beautiful park, smack dab in a not so beautiful place. But I was given free rein to do the shows I wanted to do. Probably the feather in my cap at that time was a large scale project with Mark Dion (his first in Massachusetts, our shared home state). New England Digs was a three part mock archaeological dig project in Brockton, Providence, and New Bedford (Mark grew up in Fairhaven). Shortly after Mark’s project, I started work on what would be the 10th Fuller Triennial, a project that was shelved quickly as the museum decided to go the craft route.

I was unceremoniously dismissed at this time. I think there are some interesting things that can be done with craft and a huge number of conceptual artists are working with its methods and materials but the Fuller was not so interested in that end of the spectrum. I still find it funny that later I would go on to teach in the Glass Department at RISD – which has some of the most exciting artists working in it.

I was at the Fuller for 3 years, so that summer of 2002, I spent freelancing. I was actually living at Pam Allara’s house while she was in South Africa. I curated the two inaugural projects for the Art Interactive in Cambridge, did lots of freelance writing (including an essay for Linda Leslie Brown’s show at Suffolk. I think you were curating the gallery then, right?).

CG Yes.

DM That fall I got two jobs right at the same time – a freelance large-scale public art exhibition in Lower Merion, Pennsylvania and the job as gallery director/curator at Artspace in New Haven, Connecticut. I took both. The project in PA was just a two year, one exhibition gig (I worked with Mark Dion again, former Bostonian Kelly Kaczynski, NY artist Bob Braine, and it was my first project with Nari Ward, whose show is up at MASS MoCA right now).

All of my previous work really prepared me for Artspace. With a staff of three, it was an all hands on deck institution where I would paint the walls, drive the Uhaul to NY to pick up artworks, curate and write. I did this for five years, growing the space’s programming from one mostly showing local artists to one that showed those same artists in conjunction with national and international artists – fostering a larger dialogue for the artists of CT.

There were two rather large-scale shows at Artspace (these very much prepared me for the large amount of new work commissions that we do at MASS MoCA). The first was Factory Direct: New Haven, a project that placed 12 artists in residence at 12 different factories throughout CT, making new work from the experience. The idea for the project came from Michael Oatman – the Troy, NY artist who did a similar project in that city (and who now has the brilliant airstream trailer installation at MASS MoCA. Oatman was an artist in my version of Factory Direct as was Jane Philbrick who is now finishing up a large garden project that will open at MASS MoCA on September 24th). The second was 50,000 Beds, a project by Chris Doyle, that was collaboratively organized by Artspace, the Aldrich Museum, and Real Art Ways. This project commissioned 45 artists to make short videos in hotels, motels and inns across CT, the exhibition showed simultaneously at all the museum (15 videos at each institution) in the summer of 2007.

That brings me to MASS MoCA...