Umberto Romano (1906 - 1981) and the New Deal

Exhibition at Cape Ann Museum

By: Susan Erony - Dec 16, 2024

I want to start by giving you a sense of Romano and his place in the history of Cape Ann art, as he was one of the modernists who came here and was an active full time resident of the East Gloucester art community.

Romano was born in 1905 in Bracigliano, Italy, in the south, near Salerno, and his family emigrated in 1914 to Springfield, Massachusetts. Romano was nine, old enough to have absorbed an Italian culture. He did well enough in the arts in high school to win sufficient money for four years of study at the National Academy of Design in New York. In 1926 and 1927, a Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship sent him to the American Academy in Rome where he became interested in Renaissance and earlier Italian artistic styles. He retuned to New York City in 1928 and began to show at the Rehn Galleries. In 1933 he opened an art school on a boat in East Gloucester and in 1937 bought the former Gallery-on-the-Moors building.

Here are a couple of his paintings from the thirties, which you can see or have seen already in this show:

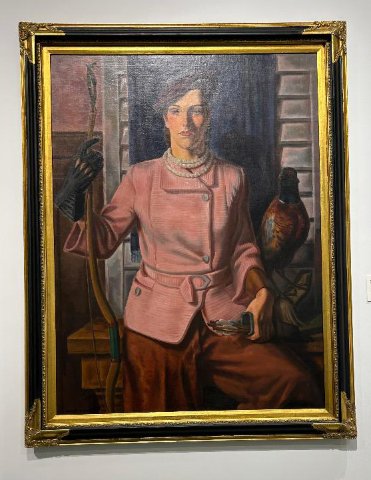

- Umberto Romano, Diana, oil on canvas, c. 1930

Romano’s earlier style in Diana is classical in that it is realistic, straightforward, dramatic and uses the Roman goddess of the hunt as its subject. Diana is an idealized and heroic figure, as well as mythological, but she is here dressed as a contemporary woman and based on Romano’s wife, Florence Whitlock. So Romano is saying something about human nature, contemporary women, a certain type of woman who has always lived and stood out, and perhaps his wife.

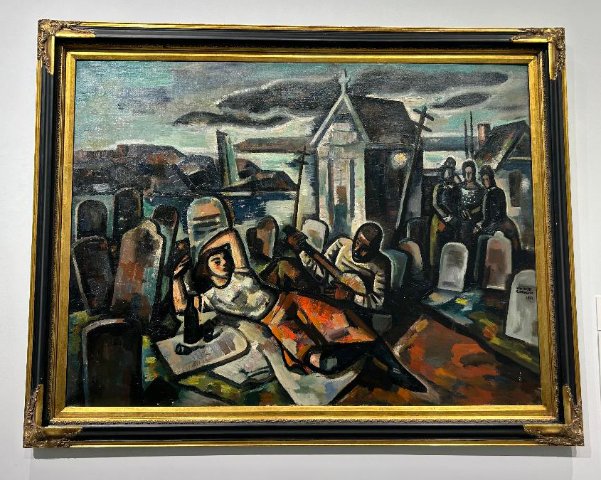

- Umberto Romano, New England Tragedy, 47.5 x 35.5 inches, c. 1934.

Romano, like his art, was a romantic, a larger than life figure. By the mid 1930s he adopted the heavy black outlines of Expressionist work, a dramatic device used by Georges Rouault, Max Beckmann and other European practitioners. You can see the same black framing in work by Theresa Bernstein and Marsden Hartley, both modernists and expressionists with ties to Cape Ann. In New England Tragedy Romano set the scene above an oceanside cemetery reminiscent of Gloucester. Three figures, perhaps the Fates, the three female goddesses who decide one’s destiny, watch over a reclining, inviting woman serenaded by a man.

1934 was also the year Romano began to teach at the Worcester Museum School, where he became director until he retired in 1940, a retirement somehow linked to a divorce from his first wife. He then established the Romano School of Art in Gloucester and taught figure, portrait and landscape painting.

Romano was unable to serve in World War II, but he was devastated by its events and his art changed, becoming darker and more melancholic. He was not alone in this kind of change. Artists in Europe and America were affected not only by the events, but also by the enormous amount of imagery of horror in newspapers and newsreels. The war itself, the liberation of the concentration camps, and Hiroshima were everywhere in an unprecedented way. As art changed dramatically after the Civil War and WWI, it not surprisingly did so again after 1945. Just as society did

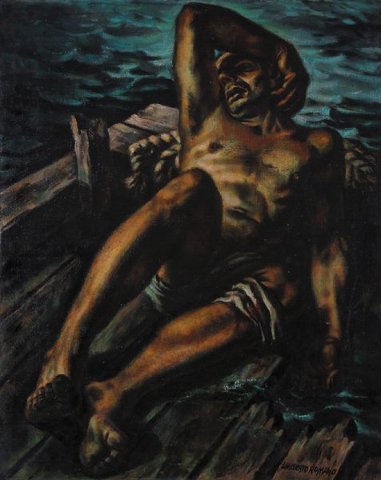

- Umberto Romano, Cargo, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches, c. 1942-43

Cargo pays homage to the sacrifices of Merchant Marines, whose unarmed ships were sent to deliver supplies to American troops. If attacked by Axis powers, as Romano infers by the one survivor on a makeshift raft, they were often stranded, sinking with their civilian crews. Expressing his feelings about the times in a 1944 exhibition catalogue, he said,

Can one go on painting serene, calm, undisturbed, unemotional paintings, in such turbulent, intensely chaotic times? Turn on your radio. Glance at the screaming headlines. Throw open your windows and the air is dense, seething, throbbing with pain, sorrow, hatred; full of black, hateful passion.

Romano and his art were larger-than-life, and he cared about and focused most of his art work on the human condition. He took both his art and teaching seriously and taught academic, rigorous and formal classes. In 1947, he illustrated an edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and in the 1950s, he did a series celebrating great men of history, those who rose above human sorrow. To his dismay, his dark, expressionist and socially concerned work had no audience on Cape Ann, and in 1965, he finally gave up his school and home and moved to Provincetown.

Romano was successful — he was able to support himself with his painting and teaching even during the Depression. He thus had not qualified for relief work with the WPA, which was a relief program, but was hired by the Treasury Section of Fine Arts to paint a six panel local history mural at the Springfield Post Office in 1935. We will be looking at that mural in a bit, but I want to speak to you about the New Deal itself first.

The New Deal

Locally, nationally and internationally, the 1930s were a terrifying decade. Europe was heading for disaster, and the climate in the United States was highly charged. Our economy was devastated and there were political ramifications. In 1932, the stock market had lost almost 90% of its value since crashing in 1929. Unemployment was conservatively placed at 25% -- 34,000,000 men, women and children had no income. Millions lost their homes and all means of subsistence. Over 3600 banks had closed. Governments were broke. Crisis was everywhere.

In 1930, 10-15,000 men were out of work in Gloucester alone. Between 1931 and 1933, the numbers of citizens on relief doubled, and hundreds of children were unable to attend school because they did not have proper shoes and clothing. Fish prices eroded, and fishermen were out of work. Their families took in boarders, often visiting artists like Marsden Hartley, to make ends meet.

After defeating Herbert Hoover for president in 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt organized what became known as his brain trust to design an economic policy and programs to implement it. The members set out to regulate banks and the Stock Market, and exponentially increase relief and public works. Roosevelt announced the plan as a New Deal for the American people. There was huge opposition from libertarian and conservative elements, and the plan was in complete contrast to the trends in some countries toward totalitarianism and fascism.

General Hugh S. Johnson, who was in the brain trust and later head of the National Recovery Administration said, “No one would ever know how close we were to collapse and revolution. We could have got a dictator a lot easier than Germany got Hitler.” Franklin Roosevelt said, in response to a comment that if he saved American democracy, he would be the greatest president of the United States, and if he failed, the worst — “If I fail, I shall be the last one.”

In 1933, George Biddle, painter, friend and former classmate of Roosevelt, saw the Depression destroying the arts community and appealed to F.D.R. to form a project creating work specifically for artists, rather than employing them as general laborers. His inspiration was the Mexican government, which paid artists to work at plasterers’ wages “...in order to express on the walls of the government buildings the social idea of the Mexican revolution.” Art would be a means of communicating messages and changing societyThe most known of the Mexican muralists whose work Biddle saw were the following

- The History of Mexico, Diego Rivera, main stairwell of Nat. Palace, 1920

- The Epic of American Civilization, José Clemente Orozco, (Dartmouth’s Baker Library. ) 1932-34

24 panels, approximately 3,200 square feet, and depicts the complex and tumultuous history of the Americas, from the Aztec migration to the industrialization of modern society.

6. Cuautémoc Against the Myth, David Alfaro Siqueiros, c. 1944

A mural depicting an epic battle between the god Cuautémoc, and a centaur.

Biddle’s ideas led to the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) in 1933 and 1934. An emergency relief effort to provide public service jobs during a bitter winter from 1933 to 34, it and its successor program, the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, aimed to collect “masterpieces” for the federal government. The advisory committee, made up of renowned American realist painters -- Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, Rockwell Kent, Reginald Marsh, Henry Varnum Poor, Boardman Robinson -- was antagonistic to European modernism. PWAP lasted less than one year, yet it provided employment for approximately 3,700 artists who created nearly 15,000 works of art for $1,312,000

I want you see the following in order to compare the styles to Romano’s work at the time:

- Thomas Hart Benton, Achelous and Hercules, 1920 - Smithsonian

- Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930)

- Grant Wood, 'January, '1940-41, Cleveland Museum of Art

In August of 1935, Federal Project Number One (Federal One), was established by a new Works Progress Administration (WPA). It was the central administrator for arts projects — visual art, music, theater, writing, and decorative and folk heritage, and it was a national program with regional foci/focuses. Each project had a Washington-based national director and a network of individual state and local offices. Federal One sought to legitimize artists and artwork; it reframed artistic labor as productive labor. The federal government owned everything produced, and the client of Federal One and its artists was the American people.

A desire to link culture and democracy in America was prevalent in the 1930s. There was a open belief that art was essential for everyone, and that it had the power to affect human beings and the societies they build in positive ways. Art could change society in the most humanitarian and civilizing ways. It could be a part of the daily lives of all Americans, not just of the elite, enriching the lives of everyone who encountered it.

And with federal funding, work went everywhere, and millions of Americans all over the country experienced concerts and plays, and could see original professional paintings and drawings, almost always for free. Children’s art and music classes were free, and soon adults joined in.

Artists who worked under the Federal Art Project included Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, Ashile Gorky, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Stuart Davis, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, and Willem de Kooning. The arts programs were the Federal Government’s first acknowledgement that the arts were significant in American life. Thousands of artists were able to continue developing their work at a time when it would have been impossible to survive on sales alone.

Art and democracy do not necessarily sit easily with each other, but during the Great Depression and New Deal, Communists and Madison Avenue public relations people were all suddenly part of a democratic culture. During the period, the meanings of both democracy and art were debated at length by everyone from housewives to religious leaders to academics and government workers. And done so publicly.

For New Dealers, artists were in part social workers. The artists the New Deal programs employed were as much agents of the state as artists in Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Stalinist Russia. The messages differed radically, but the use of art as propaganda for state supported goals was the same. The confluence of circumstances that allowed and even forced a unique, experimental federal arts initiative here changed the way Americans viewed and used art in the 1930s.

By July of 1939, the WPA became the Works Projects (as opposed to Progress) Administration, and in 1942, the arts programs were redirected to the military effort. All ended in mid-1943. Fortunately for American culture, the Metropolitan Museum of Art preserved 22,000 plates and thousands of photographs from one program, the Index of American Design.

The General Services Administration took over the artwork in 1949. It has been up and down since. Though the federal government never got out of the culture business, whether overtly or covertly, the days of the New Deal spirit of involvement were over.

In Gloucester, the New Deal helped fund the new State Fish Pier in 1936, was responsible for the 1940 Gloucester High School and numerous smaller projects -- draining Burnham’s Field and turning it into playing fields, putting a park in every city neighborhood, a new slate roof on and stone wall in front of City Hall and several others.

Many artists who lived or summered on Cape Ann participated in programs and were paid for their work in an unprecedented way. Most used realism based styles to depict both society’s ills and their idealistic goals and desires. The most impressive result of New Deal arts funding on Cape Ann are the collections of murals in Gloucester’s City Hall, its Sawyer Free Library, and its schools. The Rockport Post Office and public library each have a mural, as do or did several other buildings on Cape Ann.

Gloucester’s collection is considered to be the finest and most extensive one on the North Shore of Massachusetts, if not in the whole state. The murals, painted between 1934 and 1942, represent a confluence of a vibrant arts community and an intelligent program of the Federal Government during a critical period in American history.

Cape Ann artists hired to paint murals accepted that the work came with an agenda and were for public communication and already had styles suited to the mission. I strongly encourage you to see the murals at City Hall in person. They are quintessential New Deal murals, and personally, I feel rather awed by them. For here, though, I will just show you an image of one work by Charles Allen Winter in which he addresses the ideals of the city on its walls:

10. Winter, City Government, 1937

All municipal responsibilities are depicted via city planners, fire-fighters, police officers, city council members, nurses and teachers. As in Winter’s other murals, the figures are wholesome and open-faced; they are true keepers of the public trust. The classical composition, balanced and horizontal, of the mural is also supportive of a benevolent hierarchy of citizens and their government. Like many of the muralists, Winter appreciated that he was not just talking to himself or other artists, but was speaking for and to the whole community. I believe Romano felt so, too.

And now, finally, back to Umberto Romano — he turned down a well-paying job offer in order to paint murals in Springfield. He said Springfield had been good to him; he loved the city, and wanted to give back. The murals were done on heavy canvas in Romano’s Worcester studio, and he was assigned four assistants — Paul Fontaine, Leon Hovsepian, Lincoln Levison and Charlotte Scott.

Romano decided to paint the history of Springfield and its people from 1636 to 1936. He and his assistants worked from 1935 to 1937, when funding was no longer available. Romano used the social-realist style, bold and shockingly direct

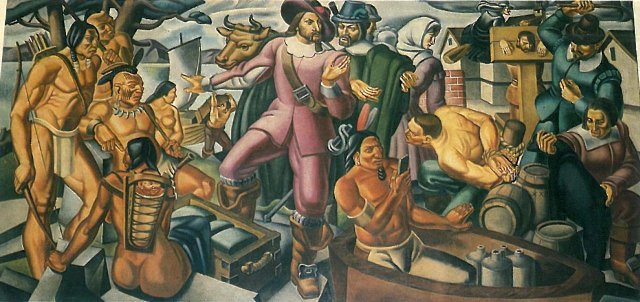

- Romano Mural 1 William Pynchon

The first panel shows Springfield’s founder, William Pynchon and one of his associates trading with local Indians for the furs that made fortunes for many of the early colonists. Pynchon bought land and corn from Native people to save the people of Springfield during bad winter.

The Indians, who had their own justice system, considered the types of punishments depicted by the Europeans degrading. The head of a cattle is near the top of the panel, signifying its introduction, which proved to be bad development.

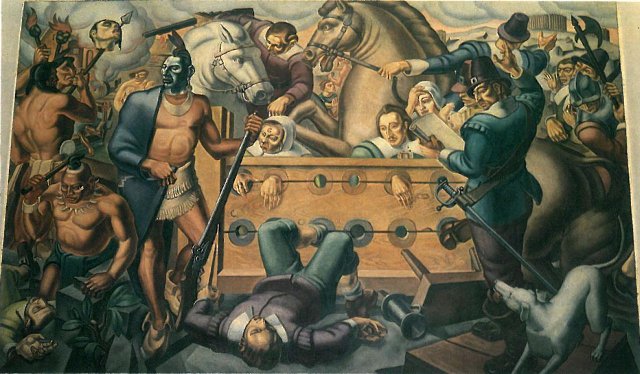

- Romano Mural 2

The attacking and burning of Springfield by Indians and English troops who fought them off. The Native Americans are now depicted as savage warriors. According to a description, the historical figures depicted in this mural died in the attacks of the Native Americans. The stockade in the center represents the increased use of corporal punishment against disobeying the colony’s leaders.

- Romano Mural 3

Court scene where a Reverend Brock defends his orthodox views and a mother complains about evil behavior of people who set bad examples for her children.

But life goes on on the right of the panel.

The third mural represents 125 years of Springfield’s history, showing the inside of a building with walls and a floor. As explained by the panel, during that time there were many internal issues with Springfield concerning conflicting religious ideas and the clash of values between different generations.

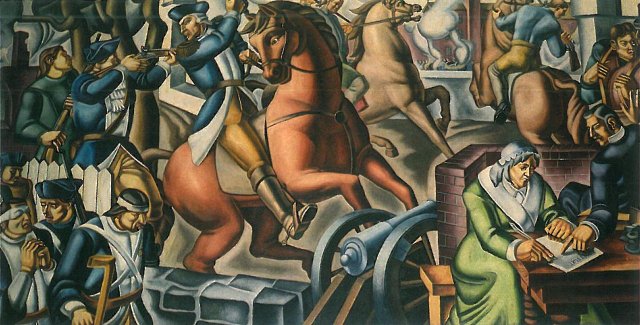

- Romano Mural 4

The American Revolution and aftermath — Washington inspires troops, then they come home to find their farms taken for nonpayment of taxes or mortgage. Daniel Shays, an ex captain, and his followers staged Shays’ Rebellion in 1786 and 1787, a protest against economic and civil rights injustices by the Massachusetts Government. Though the rebellion was put down, it had ramifications that are still debated about its influence on the writing of the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

- Romano Mural 5

The fifth mural depicts African Americans and encompasses a sixty year period, from 1826-1886, to show how the issues of slavery and abolition dominated the city, state, and nation at this time. Historical figures in this mural include John Brown and politician George Ashum.

- Romano Mural 6

The final mural shows World War I and the depression that followed.

After WWII Realism took a back seat to Abstract Expressionism, the new heroic art celebrating individual and idiosyncratic expression. It became the art of freedom, of masculinity, power and the grandeur of America. Like the Hudson River School artists, it saw the sacred and spiritual in the nature of the country itself. It was art for art’s sake, the artist again an outsider rather than another worker in society. The Renaissance idea of the genius artist who gave society a gifted visual voice was reborn. The style was triumphed by art critics, and after the War was adopted by the government as a Cold War propaganda tool. It was presented as a counterpoint to Communist collectivism and its prescribed Socialist Realist art.

On Cape Ann, the art world shift towards abstraction and nonobjective art, art that does not refer directly to a subject we can see, was the turning point when nationally important artists stopped going to Cape Ann. The final attempt to create a society of nontraditional artists was the 1948 Cape Ann Society of Modern Art, an organization formed by the merging of the Gloucester Society of Artists and the Rockport Summer Group, the latter begun in 1944.

Review of Umberto Romano exhibition.