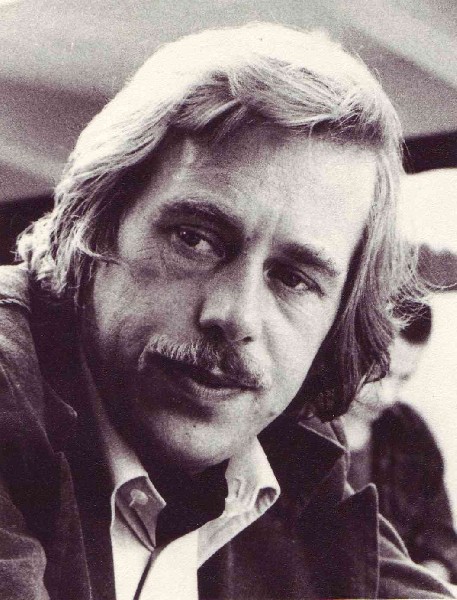

Vaclav Havel Dead At 75

Czech Playwright, Poet, Dissident Conscience and President

By: George Abbott White - Dec 18, 2011

Vaclav Havel (1936-2011) was someone I greatly admired at a distance, then meeting once in America only to realize that I had probably met him almost three decades earlier, in Prague.

It was not the playwright of absurdist dramas I encountered each time but the deeply serious writer protesting the absurdity of Soviet-imposed "normalization," the implacably idealistic leader confronting the absurdity of a nation's cynicism and resignation.

Blundering around Prague in 1972, searching for post-WWII Charles University students of Harvard's cultural historian F.O. Matthiessen, a distinguished but demoted (because Prague Spring associated) Shakespearian scholar, Zdenek Stribrny, walked me through a small theatre where, I was told years later, Havel had been present.

"Havel took a class with me on Shakespeare," Professor Stribrny said, and then with a smile, "underground, of course, and now I wonder," another smile, "whether I had given him an 'A'."

Havel's death comes as one of those things for which you believe yourself well-prepared but, when they actually occur, always come as a shock.

What is in part the shock is how long Havel survived, having lived through not only political and social harassment and physical torment in prison, not unlike the brutalized RAF pilot in the famous Czech film "Dark Blue World," but also the continuous anxiety of being an artist as well as what Conor Cruise O'Brien would call a practicing politician.

Additionally, as both friends and countrymen knew, there were the more recent physical and emotional losses, serious ones, the removal of one lung, the death of his wife Olga and his Slovak colleague in arms, Alexander Dubcek, but also, the split of the two lands in which he had come of age, Czech from Slovak, which he had been unable to prevent as the nation's new president.

Havel was too much the political philosopher to waste energy on resentment over the re-invention and rise of the old Communist Party, reframed and prosperous aparacheks in post-1989 banker's blue with pin stripes.

Understandably, his principled moralism was unable to check the sadness, even fury at the same time with the (self) elevation of soiled opportunists like Vaclav Klaus who succeeded him.

In the autumn of 1989, I remember listening to the scratchy radio transmissions with Boston emigres Heda and Pavel Kovaly. Most in the West had little idea who these brave dissident men and women were in Germany, Poland or Hungary, and chilly Stalinist Czechoslovakia just a mystery.

Then it was even more unclear why Havel was in leadership, became the spokesman. Yet Heda was reassuring, as a writer and a translator, here and there, she knew and trusted Havel. As a philosopher, Pavel respected many of the underground thinkers who had influenced him. Each assured me Havel was the real thing, the re-emeging civil society was in good hands.

Havel's plays had been opaque to me. Trust came from his "Letters to Olga"; I first read these prison writings that same fall of 1989, their message "between the lines" convinced me that here was a voice in the vein of Orwell and Camus, as well as with the personal witness of a von Moltke.

My friend at Knopf, the publisher who translated and published Havel, Bobbie Bristol, had sent me Havel's books. She was an early supporter and kept in touch with other Czech novelists and writers who had come to Canada.

So I kept trying the plays, but I kept returning to the essays and their moral center again and again, particularly, "The Power of the Powerless" and the satirical open letter, "Dear Dr Husak."

It made me want to help and so, oddly, came my tiny part in pushing forward the Czech economy in the early 90s, which led to that second meeting. Initially it was my brother pressing me to introduce Apple technology to these newly freed societies, particularly Prague. This dovetailed into Havel's visit to America, and his impressive speech to a joint session of the U.S. Congress.

It had its effect. Americans are people of the word, and the spoken word carries weight. Havel's articulate prose and his manner of delivery were gravitas incarnate. It put forgotten Czechoslovakia on the world stage and kept it there for a good long time. It announced the attempt at Central European democratic polity would have its center in Prague.

Shortly before that memorable speech, I was able to persuade Apple's CEO John Sculley (then at his apogee with the Clinton administration) to divert his Learjet to Bethlehem, PA for a meeting with "the playwright."

Havel was receiving an honorary doctorate from the Moravian College. Before the ceremonies, we found Havel and Sculley space in the former Bethlehem Steel hotel's top floor Executive Suite. They talked not only "business" but, like Havel's time with Bill Clinton, art, music, and Czech cinema!

Havel the writer eagerly embraced the new media. If Apple used my video clips for world wide HyperCard distribution thanks to specialist Jim Lengel, the chain smoking of Czech and Slovak taxi squad economic "team" used their selection of images generation interest in Washington and then Wall Street.

I imagine the pitch was: If the CEO of arguably the most creative American Silicon Valley company went out of his way (Sculley had diverted from an Apple Paris schedule) to meet with the playwright-turned-politico, perhaps you could turn a buck in those former Iron Curtain lands?

It must have had some impact, even usefulness, as a return visit took place the next year. Sculley came to Prague, and there were other meetings with Havel, this time in Prague Castle.

Apple never got the big Czech or Slovak contracts, but Havel got his Apple PowerBook each year that he was president. Apple computers did get into some Czech schools over the years and certainly, with Dr Stepan Bojar, into Prague's Charles University and its five medical schools.

For my Newton South High School's yearly vacation trips (Prague Spring), Apple was a welcoming and important early base. I have to believe all those Newton students roaming around Old Town Square brought back more than ersatz "feelings" about the "Central European Disneyland."

Hopefully, the students internalized something deeper and more long-lasting about the history, relationship and relevance of the "heart of Europe" to our own society and future.

It could well describe a small part of Vaclav Havel's legacy as well.