Kara Walker Afterword

Outtakes of Giant Sugar Sphinx at Sikkema Jenkins

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 19, 2014

Afterword

Kara Walker

Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Through Jan. 17,

530 W. 22nd St., New York

sikkemajenkinsco.com

The Triangle Trade brought slaves from Africa to the Caribbean. There to cut cane made into molasses sent to New England. Then sold and processed as rum. Ship captains were refinanced returning to Africa to purchase more slaves.

The world developed an insatiable sweet tooth which today inflicts millions with obesity and diabetes. On plantations the brutal lashes of masters opened the backs of Africans laboring in the fields.

In the American south there was the oppressive dominance of King Cotton. While in the islands one may speak of a Sugar Queen and her legions of Sugar Babies. I knew them as the penny candies of my youth called by another shameful name.

The African American artist, Kara Walker, has enjoyed a career with success, prestige and numerous awards devoted to vivid, often gruesome, pornographic and grotesque images of the Ante Bellum South and more recently the ravages caused by the sugar industry and slavery.

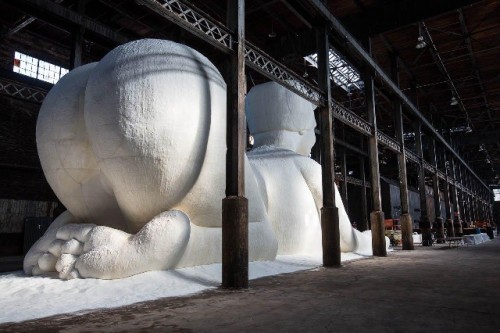

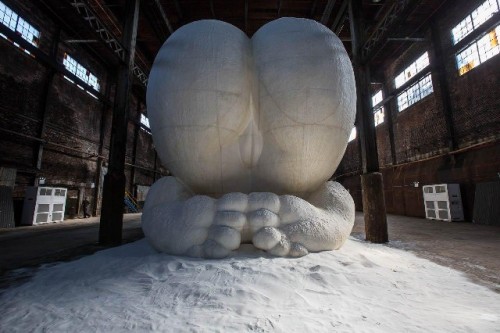

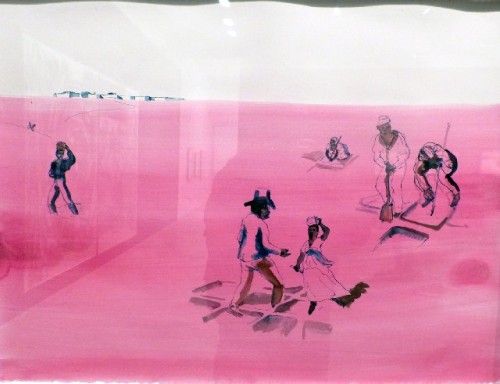

In the spring an enormous, 75-foot long carved Styrofoam sphinx covered with tons of sugar and molasses was installed in a former warehouse for Domino Sugar in the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn. The industrial setting drew throngs who cheered and sneered at this work.

The colossal, primal, prowling goddess is titled “A Subtlety.” Its wordy subtitle is “The Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World.”

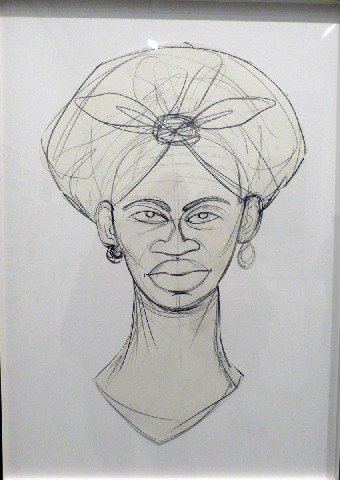

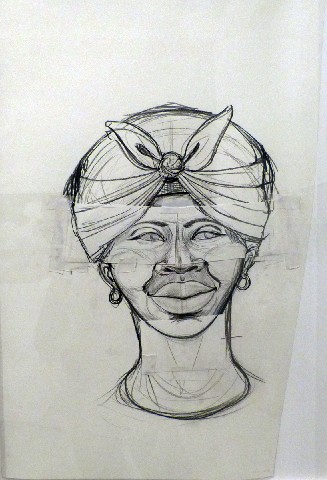

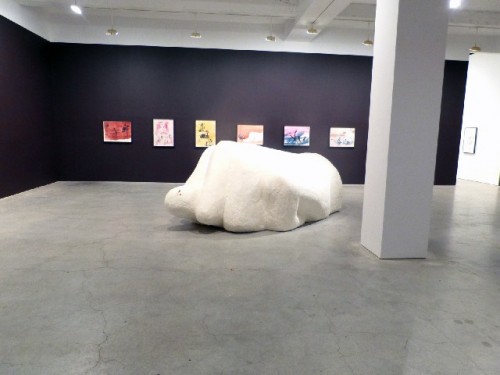

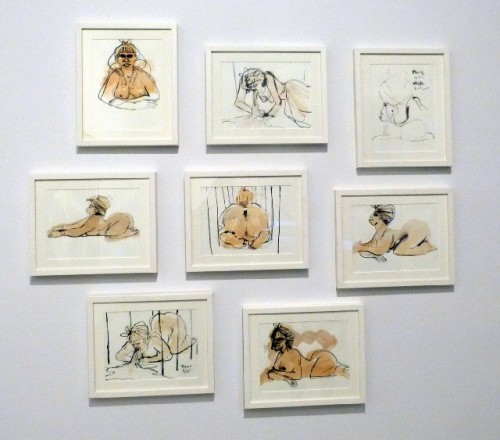

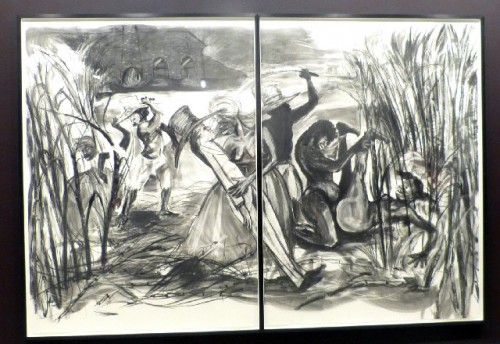

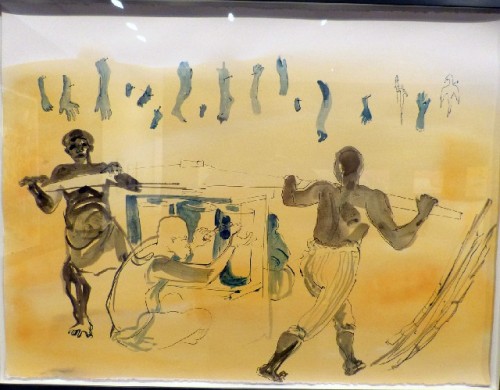

Through January 17 the Sikkema Jenkins gallery in Chelsea is showing “Afterword.” It consists of studies of the sphinx, life sized, molasses coated sculptures of slave boys with large wicker baskets for cane, and related water color drawings with sheets of hand written text.

Other than one, large scale silhouette of the Domino sculpture there are none of the cut paper collages, often of enormous scale, which established her with curators and collectors.

Oddly this exhibition of brushy works on paper brought me back to initial exposure at the Bernard Toale Gallery on Newbury Street in Boston. At the time she was finishing studies at Rhode Island School of Design where she was regarded as a prodigy. Indeed she started quite young in the studio or her father, Larry Walker, who was the chairman of the art department at the University of the Pacific.

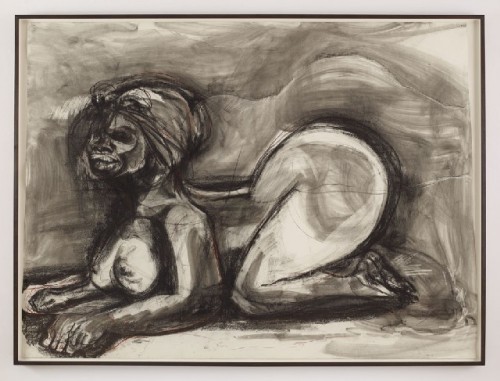

On first exposure the crude, expressionist wash drawings, then and now, had a freshness, energy and in your face confrontation. In the 1990s she was out front of the dialogues and debates provoked by the gruesome realism of the recent Academy Award winning film Twelve Years a Slave.

You don’t want to get caught on the wrong end of that conversation. One has to factor an intimidation element as a contributor to her accolades. Among her awards has been a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1997 at the age of just 28. Being declared a genius can be daunting for one so young. “To joke about it isn’t necessarily to dismiss it,” Walker said, “but it is to acknowledge the complete folly of that whole notion.”

As I learned during her lecture at Williams College a couple of years ago, Walker tends to be inarticulate, muddled and entangled by the Gordion Knot when attempting to articulate her ideas before an audience. Unlike her sugar sphinx Walker is no oracle.

While white liberal critics have mostly praised Walker for her imagery the renowned African American artist and elder spokesperson, Betty Saar, in 1997 at the moment of being declared a genius did not give her younger colleague a free pass. Saar launched a letter-writing campaign against Walker’s work. She objected to negative stereotypes of blacks as both victims and aggressors that catered to the expectations of whites. Saar expressed “a sense of betrayal at the hands of a black artist who obviously hated being black.”

Be that as it may with this latest, ambitious, monumental project sponsored by Creative Time Walker is enjoying the sweet smell of success. For me the difficulty of the Sikkema Jenkins exhibition has more to do with the quality rather than the content of the work. She doesn’t paint very well. The drawn studies for the sphinx are more firm and compelling than a suite of aqueous narratives of the slave driven sugar industry.

What seemed fresh and expressionist when she emerged in those early Boston shows, now, at mid-career, strikes me as crude and inept. The middle period of the giant cutout installations were flat, graphic and masked her inability to create compelling chiaroscuro or finessed rendering with the brush. This latest exhibition reveals no development of watercolor technique since the 1990s.

This was most evident in an homage to Turner’s masterpiece in the Museum of Fine Arts "The Slave Ship." It is a painting which I looked at and taught over decades. One never tires of its flaming sky, masts set against a storm at sea, chains and hands sinking below the waves with giant fish feeding on the human ballast thrown over the side.

The harrowing and galvanic 1840 painting by England’s then greatest master, J.M.W. Turner, was a part of the debate that ended slavery in Great Britain. That wouldn't happen in America until the Civil War some twenty years later.

In the work on view in the gallery, which alters Turner’s composition into a panorama on paper, her approach mimics the master’s but in an embarrassingly slapdash manner that draws attention to her ineptitude. That singular work has been deconstructed as an instantly recognized simplistic signifier of her agenda. Perhaps I am harsh but the work of Turner is more sacred to me than that of Walker.

Behind a curtain one enters a room with a video of the Domino installation. Watching long enough to catch the drift I failed to find any insights. The film was mostly about the many and diverse crowds that came to view the piece. It zooms in on emotionally entranced adults and attractive teenaged girls taking selfies.

So, thanks a lot, people liked the show; which is more or less what one concludes about its sidebar in Chelsea.

Okay back to the subject matter. Of course it is important and a terrible part of our history, identity and fucked up political legacy. For that, yes, thanks Ms. Walker for bringing it to our attention.

From here, however, we must suck it up with a far deeper, nuanced, painful, introspective examination. Yet again that action is being played out in the streets of American cities. Not, my friends in museums and art galleries. It’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

Perhaps it is time for Walker to fast forward her work into the here and now. At mid-career, will she one day emerge as an elder statesman? The sphinx piece is a step in that direction. It remains to be seen whether it is the right move. Bigger is not always better.