Rethinking Abstract Expressionism: Beyond the Canon

Exhibitions at Robert Miller Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 20, 2008

Beyond the Canon: Small Scale American Abstraction 1945 to 1965

Robert Miller Gallery

Curated by Amy L. Young

524 West 26th Street

New York, New York 10001

212 366 4774

November 20 through January 3

Link to Robert Miller Gallery

Modern Masters: American Abstraction at Midcentury

Organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Curated by Virginia A. Mecklenburg with a contribution by Tiffany D. Farrell

Catalogue 256 pages, illustrated

Published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with D. Giles Limited, London, 2008.

Itinerary:

Patricia and Philip Frost Art Museum; Florida International University, Miami.

November 29, 2008- March 1, 2009

Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

June 14-September 6, 2009

Dayton Art Institute, Dayton, Ohio.

October 10-January 2, 2010

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia.

November 13- February 5, 2011

Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee.

March 19 – June 19, 2011

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

October 7- January 1, 2012

Suitcase Paintings: Small Scale Abstract Expressionism

Curated by April Kingsley with essays by John Corbett, Jim Dempsey and Thomas McCormick. Organized by Georgia Museum of Art; Art Enterprises, Ltd. And TMG Projects. Published 2007. Traveled 2007-2008.

Abstract Expressionism Other Dimensions

Curated by Jeffrey Wechsler, with contributions by Sam Hunter and Irving Sandler and excerpts from writings by William Seitz and Matthew Lee Rohn. Organized and published by the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Traveled 1989-1990.

Too often terms such as Abstract Expressionism are generic with an equivalence of one size fits all. In the current research and dialogue about the movement of Post War mostly New York based artists there are intensive efforts for scholars, critics, and curators to further define and extend what is meant and covered by such a broad term. There are other terms and definitions such as Action Painting as advanced by Harold Rosenberg. The artists he championed were often pitted against those endorsed by his rival Clement Greenberg.

Between them, Greenberg and Rosenberg, as the leading critical thinkers of their era, defined the major players among what has become accepted as Abstract Expressionism. Artists included within this purview do not always seem suited to its ground rules, while other artists, because of issues of gender, race, geography and visibility are simply not included. A wider definition is conveyed by the term New York School. Or the more catholic approach of Irving Sandler who attempted to chronicle those passing through a moment in time and space as "The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism." (1982). As an officer of the seminal Artists Club he largely considered who came and went in that organization as well as artists who drank, argued and brawled at the Cedar Bar.

From the fog of war of the period has emerged a canon of its giants. They are usually male and given to work on large expanses of canvas. They may or may not conform to Greenberg's criteria of flatness and the all over canvas or the integrity of the picture plane. Greenberg as high priest and grand inquisitor was given to pronouncing who was in and out or right and wrong. In this approach the figure or aspects of representation were viewed as anathema.

Few if any critics or curators make such pronouncements today. The range of contemporary art is so diverse that such sermons from the mount would be viewed as absurd or deranged. Instead of clear and authoritarian pronouncements critical thinking today is bogged down in art speak. The more esoteric the better and the fewer who follow or understand what is being stated the more important and profound it appears. It makes one long for the punch and charisma of the writing of Greenberg and Rosenberg or the arts journalism and eye witness accounts of Sandler.

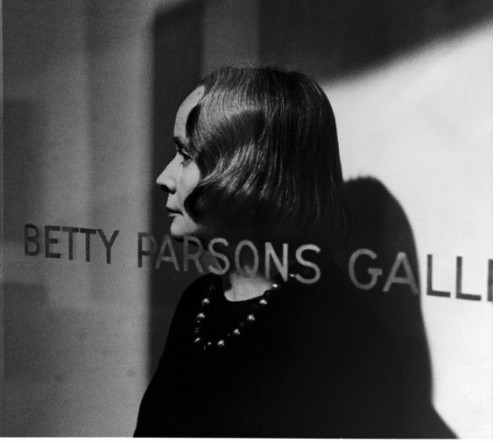

The artists whom we consider today to be abstract expressionists had some common traits. One may list and define them but we are left with work as diverse as Pollock's drips, deKooning's women, Rothko's fields of color, or the proto minimalism of Newman and Reinhardt. Where to fit the surrealist influences of Gorky and Baziotes? One may also take the approach of tracking artists who showed with Peggy Guggenheim or later Betty Parsons and eventually Sidney Janis and Martha Jackson. Or were included in seminal exhibitions such as "New Images of Man" at the Museum of Modern Art with its agenda of showing the return to the figure.

The catalogue and exhibition from the Smithsonian American Art Museum "Modern Masters: American Abstraction Midcentury" curated by Virginia Mecklenburg provides a handsome, cohesive and concise summary of the major individuals and events of the movement. Drawing from its own collections this traveling exhibition at six museums through 2012 provides a stunning and insightful resource. It is a wonderful starting point for a new generation of artists and scholars. All of the key issues, personalities and documents have been neatly compiled. Because of its great resources the catalogue, for example, was able to seek and afford permission from the archives of Life Magazine to reproduce its famous spread on Jackson Pollock "Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?" Or, a few pages later a facsimile of the article "High-Brow, Low-Brow, Middle-Brow" and the famous photograph titled "The Irascibles" which with the absence of Fritz Bultman, Hans Hoffman, and Weldon Kees, is now considered as the group portrait of the Abstract Expressionists. The photo included a single woman, Hedda Sterne, now largely obscure, but not the better known Lee Krasner and Elaine deKooning.

The Smithsonian exhibition and volume has a somewhat official and encyclopedic tone. It is not an example of ground breaking curatorial or critical effort. As much as possible it conforms to the conventional wisdom but also bends in the direction of including more women and artists of color. This appears to be more feel good tweaking than a real reexamination of the era and its issues. One test of this are lapses in relating the issues involved with the return of the figure and "New Images of Man." The 1959 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art by Peter Selz established many false positives and disconnections. The emergence of Figurative Expressionism was never adequately explored and that effort was sabotaged by the sensation of the New Realism of Johns and Rauschenberg which conflated into Pop Art.

By continuing to revert back to the Selz project and other flawed efforts the important story of Figurative Expressionism has not been adequately covered. While Mecklenburg includes Emilio Cruz, an African American artist who showed with Martha Jackson, it is disappointing that the text mentions but does not illustrated or include in the exhibition the far more important and influential work of another African American artist, Bob Thompson, who also showed with Jackson. The other leading Figurative Expressionist artists- Lester Johnson, Jan Muller, Tony Vevers, George Segal, Jay Milder and others who showed with the seminal Sun Gallery in Provincetown- are not mentioned. The West Coast figurative expressionist artists David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, Elmer Bischoff, Paul Wonner and Nathan Oliviera are rightly considered but Joan Brown is not. Early Leon Golub in Chicago and Hyman Bloom in Boston are major omissions from the discussion of Figurative Expressionism.

In the telling and retelling of art history there is an emphasis on the familiar. Often, the work and estates of particular artists are forgotten or mismanaged. The heirs as non artists are often clueless about how to deal with their legacy. The book on abstract expressionism, or later, figurative expressionism, is closed to new members unless there is some driving force. Often this is dictated by the market. If prices hold their own or increase in value there is motivation to dig deeper for fresh material. A strong market in abstract expressionism, for example, encourages research and discovery.

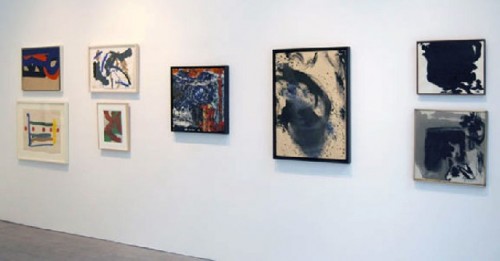

The exhibition curated by Amy L. Young for the Robert Miller Gallery "Beyond the Canon: Small Scale American Abstraction 1945-1965" is a good example of this phenomenon. There are 60 artists in the large exhibition which fills the space of the gallery. Referring to a check list with thumbnail images it was challenging to find and identify work by well known artists like Gorky, Krasner, and de Kooning as well as unfamiliar artists. One work in particular had me riveted as well as stumped. Elements looked terribly familiar. It proved to be a painting by Alfred Leslie when he was a Third Generation Abstract Expressionist before he went over to the dark side of figurative realism. Little of Leslie's early work survived a fire that destroyed his studio. There were many such stumpers and surprises in a lively and fascinating new take on seemingly familiar terrain.

On many levels this was a museum level exhibition with many tangents for further research. It is unfortunate that there was no catalogue for the project. Young discussed with us how the exhibition came together with just three months of lead time. It drew entirely on New York galleries, museums, and private collections. In the process of organizing the exhibition there were many discoveries and connections all of which, because of deadlines and logistics, did not make it into the show.

Young stated that Robert Miller Gallery has an ongoing commitment to presenting abstract expressionist artists so she was drawing upon well established sources. She also stated that the exhibition "Suitcase Paintings: Small Scale Abstract Expressionism" curated by April Kingsley, had been a source of inspiration for the Miller exhibition. Young was generous in providing catalogues of the Kingsley show organized for the Georgia Museum of Art which traveled in 2007-2008 as well as the publication for the traveling exhibition "Abstract Expressionism Other Dimensions" (1989-1990) curated by Jeffrey Wechsler (contributions by Sam Hunter and Irving Sandler, and excerpts of writings by William Seitz and Matthew Lee Rohn) for Rutgers University.

One paradigm of Abstract Expressionism was the death of easel painting. Greenberg made much of the fact that Pollock rolled out canvas on the floor of the East Hampton studio and worked above, around, and from all edges of the support. It was this mural scaled work by Pollock and his peers which played into Sandler's thesis of the "Triumph of American Painting" or the Marxist theories of Serge Guilbaut's, much debated and ridiculed, "How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art." These accounts largely focus on the machismo of epic scaled paintings that captured the global spotlight and shifted the locus of the international avant-garde from Paris to New York. Much of this is summarized in the Smithsonian exhibition and catalogue. In that sense it conveys the conventional wisdom.

The point of the Miller (Young)/ Kingsley/ Wechsler projects is to firmly demonstrate that even the leading artists of the loosely configured movement often worked on an intimate scale with no less compelling results. It is at the heart of the Ellen G. Landau claim of authenticity in the "Pollock Matters" exhibition and catalogue for the McMullen Museum of Boston College. Part of the Landau thesis is that it is plausible that Pollock may have created a series of small and experimental works.

The important concern is that the canon created by Greenberg and Rosenberg and other "first generation" critics, curators, collectors and dealers is due for reconsideration. This is an ongoing process as well as something of a growth industry for young scholars presenting papers at the annual meetings of the College Art Association. There are yet to be discovered troves of material in the estates of lesser known artists particularly women and individuals of color.

There are many forces driving the engine of research and discovery. The motive may be race and gender or sexual preference. Or increasing the value of an estate. But as galleries, curators, and critics put their shoulders to the wheel let us hope that the most significant agenda is to find and promote compelling work. There are many interesting artists who never got what they deserved the first time around. We see that all the time as the art world is known for being elitist and trendy. There is a constant turning over of the compost heap of contemporary art. In the current economic crisis an entire generation of emerging artists is due to slip into oblivion. In some ways this is a welcome phenomenon. As the tides pound the beach there is a cleansing process. But as these exhibitions and publications reveal the tea leaves get sifted and reinterpreted. It is always rewarding when important work resurfaces.