Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT

Celebrating a Remarkable Legacy

By: Zeren Earls - Dec 21, 2011

On December 8, ACT – the program in Art, Culture, and Technology at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning – paid tribute to artist and educator György Kepes, founder of the CAVS, and to its Fellows, who continued the Kepes legacy of “art on a civic scale.” Building on this legacy, the ACT program envisages artistic leadership initiating change through a critically transformative view of the world, with a civic responsibility to enrich cultural dialogue.

The program took place in the ACT Cube at the Wiesner building. Ute Meta Bauer, ACT Associate Professor and head of the program, welcomed the guests and introduced Márton Orosz, the first György Kepes Fellow for Advanced Studies and Transdisciplinary Research in Art, Culture, and Technology. Orosz is writing a monograph on Kepes, who founded the CAVS in 1967 as an artist fellowship program, in order to advance “cooperative projects aimed at the creation of monumental scale environmental forms,” while fostering the “individual creative pursuits” of the artists involved.

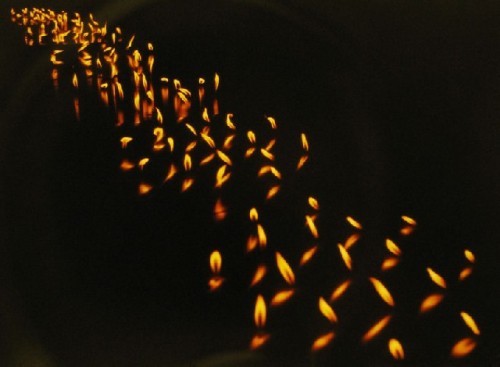

My late husband Paul Earls, a composer, was both contributor to and beneficiary of this program. Invited by Kepes in 1970, he joined the CAVS, looking for a visually engaging analog to his electronic music. With the resources available to him at MIT, he developed multicolor laser projections to accompany his music, ultimately leading to exhibitions and large-scale events during his 25-year tenure, which also encompassed numerous collaborative works with other Fellows. One example, conceived by Kepes, is Flame Orchard, in which a large box emitted gas flames dancing to Paul’s electronic music.

Another collaborative work by Paul, Dr. Allan Hobson, and several visual artists was Dreamstage, a multicolor portrait of the sleeping brain, which was created within the context of Kepes’s prophetic vision that “the separation of art and science in our minds is no longer useful and will not bear close scrutiny.” The catalogue of the exhibition at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center included excerpts from Kepes’s book, The New Landscape, with the author’s permission.

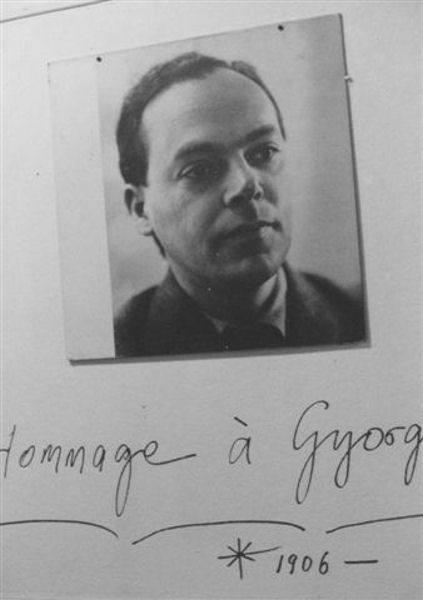

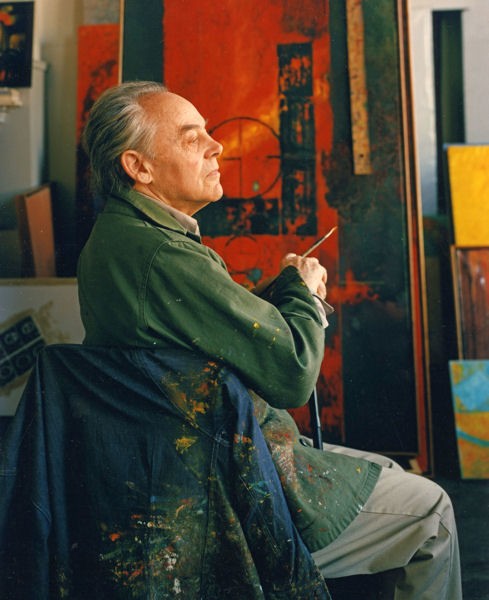

Orosz’s presentation was a summary of Kepes’s multifaceted accomplishments as painter, photographer, and graphic and light artist, in addition to his pioneering explorations in the use of science and technology toward a new visual language and civic-scale art. Kepes, born in Hungary in 1906, arrived in Chicago in 1937 upon the invitation of László Moholy-Nagy to head the Light and Color Department of the New Bauhaus. He joined the MIT faculty in 1946 as professor of visual design in pursuit of his belief in the interconnection of art, science, and technology. He established the Society of Liberal Arts, thus initiating discussions on modern art at MIT. While his Vision + Value publications championed a single integrative process of visual education, his proposed civic projects heralded a new creative fusion, emphasizing the role and function of visual design as a form of social engagement in urban environments.

Kepes retired in 1974, leaving the directorship of the CAVS to Otto Piene, one of six first-generation Fellows at the Center. Under Piene, the CAVS changed direction, adding sky art to the collaborative projects, in addition to expanding their international scope. One such project was Centerbeam, created in 1977 for Documenta 6, in Kassel, Germany. Following Orosz’s lecture, the audience enjoyed a screening of a newly restored 13-minute documentary of Centerbeam, a 16-mm color film co-directed by late MIT Professor Richard Leacock and CAVS Fellow Jon Rubin.

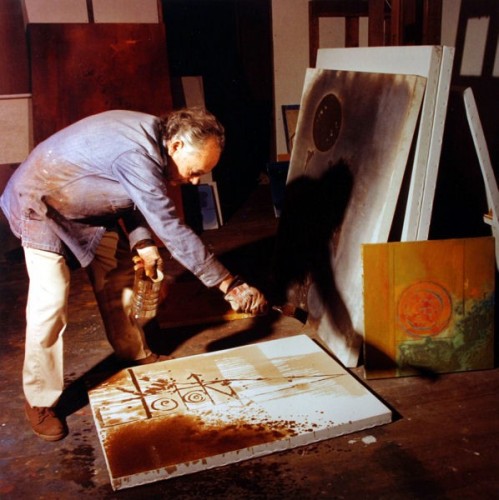

Conceived by Lowry Burgess, Centerbeam was an outdoor sculpture combining a 144-foot-long water prism, holography (Harriet Casdin-Silver), an argon-neon line encased in a glass tube (Alejandro Sina), an ice line (Carl Nesjar), and laser projections (Paul Earls) on steam clouds (Joan Brigham), along with poetry by Mark Mandel. Aldo Tambellini engaged people by having a live feed into monitors where they could see themselves as they viewed the piece. Artists Marc Palumbo and Bill Cadogan assembled the different units of this technically complex work. Kepes was invited to participate in the project by submitting an image to be redrawn in laser light and projected onto steam. The image he chose was that of an envelope, entitled To Whom It May Concern after a painting by the same name.

Moderated by João Ribas, curator of the List Visual Arts Center at MIT, a panel discussion on Centerbeam followed with the collaborating artists, who are still around. Piene explained that Burgess’s concept had been one of three ideas proposed, including one of his own, and had received enthusiastic support from the Fellows, who wished to participate in Documenta. Brigham mentioned how the sculpture had been tested in the back alley of the CAVS, attracting many passers-by to the multimedia spectacle and signaling that the artists “were onto something.” Elizabeth Goldring, an ACT fellow, who was then project director of Centerbeam, described the public reaction in Kassel, where people had wondered “whether this was art,” although attracted to the sculpture day and night, as its appearance had varied with the changing environment.

In the summer of the following year, 1978, Centerbeam was installed on the National Mall near the Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Again the sculpture attracted large crowds, who wondered what it was. This time a performance element was added to the spectacle during the final three days to mark its closing. Paul Earls’s Opera Icarus, based on the Greek myth of a boy who wanted to fly, was adapted for the outdoor performance. The late John Fleagle, who sang the part of Daedalus, was lifted to the sky by Piene’s inflatable helium tubes; the Columbus Boys Choir of Princeton sang the part of Icarus, accompanied on the harp by my son, Selim. A most unusual performance on the Mall.

Back in Boston I was directing First Night, the city’s New Year’s Eve celebration, which featured many environmental projects. Kepes, although retired, remained a close friend and neighbor. Over a drink at his house, he complimented my efforts in altering the public’s workaday perception of the cityscape, and invited me to his studio to choose a painting as a gift. Appreciative of his generosity, I asked why he did not have any of his work where he lived; “I don’t like to look at myself,” he replied. The only works of art in his house were Persian miniature paintings, of which he was particularly fond. The featured elements of his sparsely yet beautifully furnished living room were four Breuer chairs and a screen created by flower arrangements in vases of different heights on a low bench. I visited Kepes’s studio to choose my gift – a large oil on canvas in blue, enriched with fine sand from Cape Cod and captioned Braille Rainbow. The painting is still a treasure in my living room.

In recognition of Kepes’s passion for civic-scale art, I invited him to design a poster for First Night 1984. By holding a sparkler in front of a large-format Polaroid camera, he created an image of light, symbolic of the fireworks that ended the celebration. During my tenure (1980- 1994), many CAVS Fellows – Mitch Benoff, Joan Brigham, Lowry Burgess, Mira Cantor, Harriet Casdin-Silver, Paul Earls, Jon Goldman, Michio Ihara, Chris Janney, Ragnhild Karlström, Laura Knott, Otto Piene, John Powell, Seth Riskin, Bill Seamans, and Ellen Sebring – created works which transformed the city’s streets, shop windows, barren walls, plazas, and parks, enriching the First Night celebration with their unique synthesis of art, technology, and the environment. Likewise, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s first outdoor installation in the city, The Homeless Project, projected on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on the Boston Common before Wodiczko followed Piene as director of the CAVS, left the public with indelible images as they returned home from First Night.

ACT has inherited an extraordinarily rich legacy from the CAVS. The Visions and Projections program celebrated this legacy, ending with a reception for the audience. To this observer, the event appeared to be a reunion of Fellows and friends, along with a few students by the looks of those in attendance. Missing were a larger number of students, who have much to learn from this legacy of environmental art that germinated at MIT.