Morocco: Part Four

Merzouga and Daya El Maider

By: Zeren Earls - Dec 22, 2007

Merzouga

Deep in the great Sahara, surrounded by waves of towering dunes was our private tented campsite. Arriving here at sundown we got a glimpse of the sun as it disappeared behind the gigantic dunes. Since there was no electricity on the campgrounds, I relied on my flashlight to explore the site. My square tent was equipped with one cot, mattress and sleeping bag. By the bed was a nightstand with a candleholder and two spare candles, a lighter, a cup and enough space for my water bottle. A towel hung on a rope in the corner. I managed to locate the pillowcase we had been asked to bring and got my sleeping bag ready with the liner provided for us. A tented outhouse was in the back.

The dining tent was well supplied with beer and wine courtesy of our group. The camp staff served us soup, then couscous with meat and vegetables, followed by apples and oranges for dessert. After dinner we sat around the campfire and enjoyed the camaraderie of neighboring Tuareg nomads. The musicians played and sang for us, while some danced. As I walked back to my tent, the Saharan night sky above was a majestic open-air spectacle. Putting on several layers, including socks, I slid into my sleeping bag at 10 p.m. and blew out the candle.

To watch the sunrise, the camp staff woke us up at 5:30 a.m. for our climb to Erg Chebbi, which means "high dune" in Berber. Outside my door a basin of hot water for washing helped ease the morning chill. Waiting for us were pitchers of hot mint tea and coffee.

At a distance I noticed the striking silhouettes of a row of turbaned men against the towering backdrop of Erg Chebbi, the highest dunes in Morocco at 900 feet. As we began our climb, they approached us to see if any of us needed help. Since refusing help would deny them a tip, I smiled back at a handsome young Berber with sparkling eyes and white teeth that complemented his dark skin. Conversing in French I assured him that I would hold on to him if I needed help. About half our group made it to the top, as going uphill while sinking in the sand is a challenge. My companion held my hand during the final stretch of reaching the peak.

Watching the sunrise from the heights of a sand dune is an utterly unique experience. As the sun came up, the panoramic view changed from dark gray to a glowing backdrop of rose pink for a fantastic shadow play across the peaks and valleys of the dunes. Taking each other's photo( I in my red winter parka and lavender turban, my guide in his long jalaba and white turban, we were actors on this movie set. On our return he walked backwards as he pulled me by the ankles in a seated position. I was reminded of my childhood sled as we speeded downhill leaving tracks in the sand. At the end of this exhilarating adventure he spread out his fossils, hoping I would buy a few. Unique to the region of Erfoud, these sea fossils go back 350 billion years. Once they locate them, Berber families clean and polish the fossils for sale. I bought two, a sardine and a nautilus, making him very happy. He thanked me for helping him support his family.

Breakfast was ready upon our return. We helped ourselves from a spread of pancakes, apricot and fig jam and honey, omelet, orange juice, coffee and tea. Both the pancakes and the eggs had the deep color of saffron, favored in Berber cooking. Also, the eggs had been flavored with fresh cilantro, delicious. The outdoor setting under the clear blue sky and the warmth of the early morning sun made this breakfast all the more memorable.

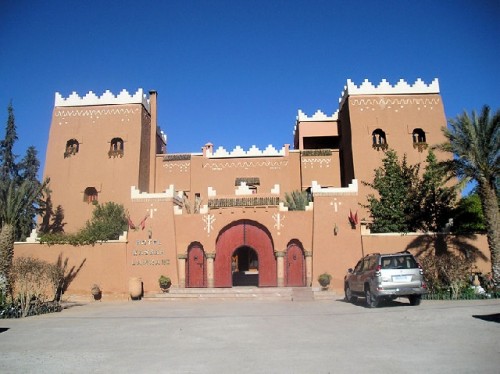

The next venture into the desert was on the back of a camel. For about an hour we rode camels that were tied together as two caravans of eight, with two herders, one in front and one in back. The stillness of the desert was wonderful, while its surface offered shadows, patterns created by wind, and animal tracks (kangaroo mouse, fox, beetle). Meeting up with our land cruisers, we headed to our second private desert camp with several noteworthy stops on the way. At the Kasbah, now a museum of Berber crafts were rugs, calligraphy, embroidery, clothing, jewelry, saddlebags and Jewish artifacts.

In Rissani we went to a ksar, where extended families live communally by sharing food, fuel, etc. This is an adobe complex with one gate to the outside, all others opening onto the fields. The community has its own rules and regulations overseen by a council of elders. Because of intermarriage among 160 families from one extended family group, the mortality rate is high. Children are promised for marriage at age seven; girls marry right after puberty. To discourage divorce, a groom receives a sacrificial goat. We visited a date Berber woman, who told us that she had had five children, but only one had survived. She did not know her son's age or her own age. She did not remember her mother, because she died very young. Her husband was sick in the hospital. Due to communal solidarity, nobody goes hungry or homeless in Morocco. Social problems will arise when solidarity disintegrates.

The visit to the fossil factory was fascinating. From a quarry in the mountains large blocks of marble are excavated. At the factory they are sliced using a cutting machine with a diamond blade imported from Italy. At the rate of one cm. an hour, it takes ten days to slice a block, revealing the embedded fossils, which are 350 billion years old. After washing, the fossils are chiseled out and polished, first with an abrasive stone, then by hand with sand paper and finally by buffing. The showroom featured beautiful marble tables with embedded fossils, along with small objects such as plates. Individual fossils were on sale as well. I bought a trilobite (three-lobed beetle), and one called a "desert rose" because of its pinkish color formed by underground gypsum deposits.

Daya El Maider

We arrived at our second private tented campsite, our home for the next two nights, deep in the sand dunes near Daya El Maidar. The tents were arranged similarly to those at the first site, except that there were shower facilities. After happily washing off our dust, we assembled for a cooking lesson from the chef. We watched him prepare chicken tajine, spreading a marinade of olive oil mixed with cumin, paprika, ginger and saffron under the skin and then cutting up the vegetables for the slow stove-top braising of this dish. A lemon pickled in vinegar, salt and water, and olives are added in the final fifteen minutes. The succulence of tajines is due to the cooking pot, also called "tajine", which has a heavy, shallow glazed dish at the bottom with a conical lid unglazed inside. As the steam rises, the clay absorbs much of it, thus reducing the amount of cooking juices.

In the morning we took a walk to the tent of an Imazighen, which means " free men" in Berber, and brought staples( sugar, coffee, chickpeas and lentils) as gifts. The women in our group presented the gifts to the widow we visited. A mother of five children, three of whom she had delivered alone, she received us with her oldest son, age fifteen. Veiled and dressed in black, she was spinning wool. A silver fibula necklace crossed her chest indicating she was married, as opposed to those worn on one side by single women. She was shy and looked down, even after the men in our group left. In a nearby tent we visited a woman with two little children, who were helping her card wool.

Outside men sold fossils; women sold crafts: dolls, beads and tie-dyed scarves fringed with bright colored yarns and sequins. Imazighen nomads live for the day, rather than worrying about tomorrow. The objects of their daily life speak of a culture rich in beauty and spirituality. Their tents are made of wool from young camels, less than ten years old. Narrow strips woven on handlooms and sewn together, become watertight with the swelling of the knots when it rains. Due to the scarcity of water in the environment the ablutions are done using sand. The most common health problem is lung disease because of dust inhaled. Major sand storms occur during the fifth and ninth months of the year.

Returning to our campsite we crossed a vast bumpy stretch of land. On the right were the dunes in varying colors of ochre and rust, casting shadows as the sunlight hit the peaks and valleys. On the left was rocky terrain, with patches of greenery indicating water. We stopped at the top of the dune nearest our camp to admire the spectacle of the lower dunes. Knowing that the Sahara stretches 2600 miles across Morocco, Algiers, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt and Jordan, I felt the magnetic pull of their majesty.

Back at camp, Aziz gave a lecture on the basics of Islam, which mean submission to God as manifested through the gestures of prayer. The five pillars of Islam are: proclamation of one God; five daily prayers(sunset, night, sunrise, noon, afternoon) each with a message; zakat or giving 2.5% of cash assets to the poor; Ramadan, a month of fasting from dawn to sunset to understand the hunger of the poor; and Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca to clear oneself of sins. The mosque is the house of God. An Imam is a theologian, who knows all sixty chapters of the Koran by rote and leads prayers. Of the one billion Moslems, 18% are Shiites, followers of Ali, Mohamed's son in law; the rest are Sunnis.

Before dinner Aziz led another walk into the dunes, carved by the winds into crescent or round shapes, where we each picked a spot to meditate. The sand's wind-rippled surface was hypnotic, a welcome solitude amidst our fast-paced adventure. We spent our final evening watching the brilliant stars in the night sky. In the morning our staff of eight Berber men, who had taken excellent care of us at both camps, played tambourines and danced for us as they merrily sent us on our way. Departing on foot, we crossed the desert plain and stopped at a Berber cemetery to learn about funeral customs.

A Berber grave is one-meter deep, and 20 cm. wide. The body is wrapped in a white shroud with the head turned to the right, then covered with dirt. Two stones, one at the head, one at the foot, mark the grave, with bigger ones reserved for the chief and his son. Customarily rosewater is sprinkled over the grave. Women do not attend burials, but stay home for three days. They wear mourning clothes for four months, and cannot remarry for three.

Driving by mud houses, date palms and barefooted children waving at us, we arrived at the farm of an extended Berber family. We walked through wheat fields, learning about henna plants and alfalfa grown as animal feed. We tasted fava beans among the familiar carrots, onions and turnips. These self-sufficient farmers also made dairy products.

Farm children attended a one-room schoolhouse built by four Berber families in 2003. Their teacher, Halit, a 24 year-old man, met us at the door and had the students greet us in Arabic. The mud schoolhouse had one door and two windows, which provided natural light, plus a blackboard in between. Students, three per desk, sat by grade from left to right in two rows. We squeezed in with the children at their desks, as there was not much room to stand. All the children were six years or older, with the older girls wearing headscarves. Nine of them were already in third grade studying math, science, reading, writing, Islam, art, physical education and first-year French. They sang Un petit chat for us, and we sang Old MacDonald had a Farm for them.