Frontline Filmmaker David Sutherland

18 Million Viewers for The Farmer’s Wife

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 09, 2020

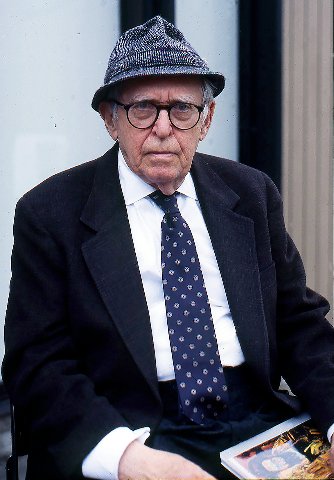

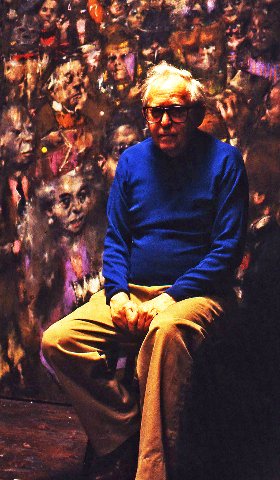

Through the end of February, the Museum of Fine Arts is presenting the special exhibition “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Fine and Death.” As teenagers he and Jack Levine were given unique tutoring by Harold Zimmerman, a teacher in Jewish settlement houses, and Harvard professor, Denman Ross.

With the German immigrant artist, Karl Zerbe who taught at the Museum School, the trio comprised the first generation of Boston Expressionists. They in turn inspired later generations working in aspects of figuration that are unique to painting in Boston.

After mustering out of the army in 1946 Levine moved to New York where he married the artist Ruth Gikow. He remained proud of his Boston roots and was an avid fan of the Red Sox. Bloom turned inward, ever more visionary and reclusive.

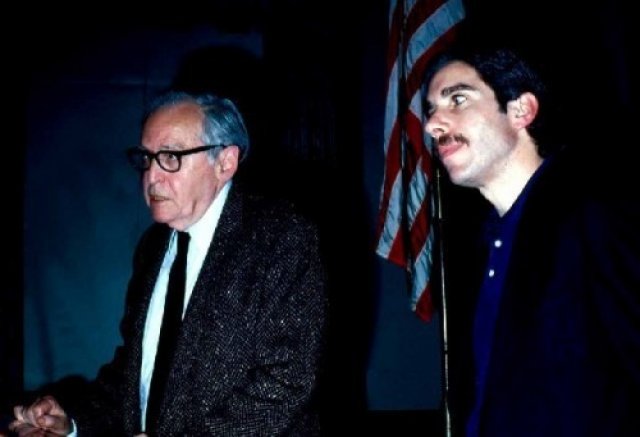

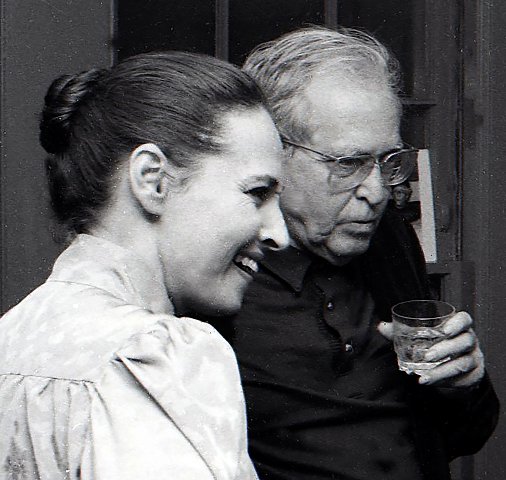

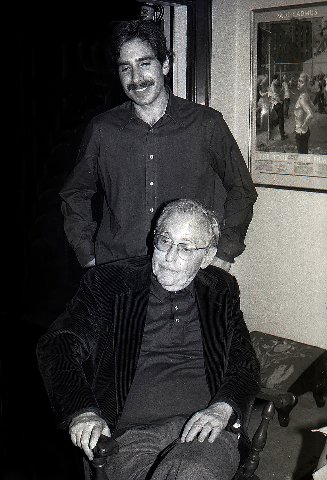

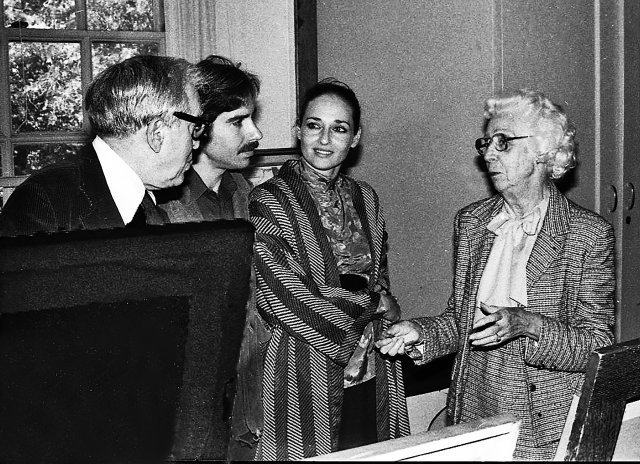

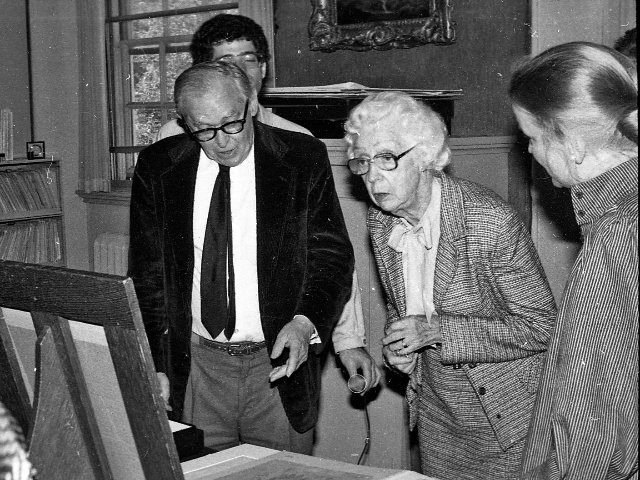

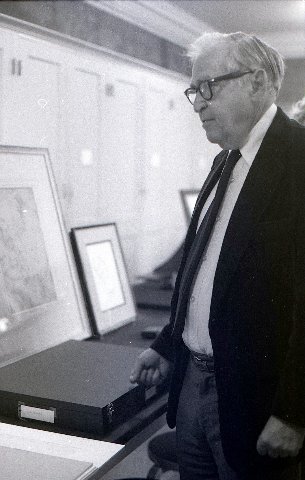

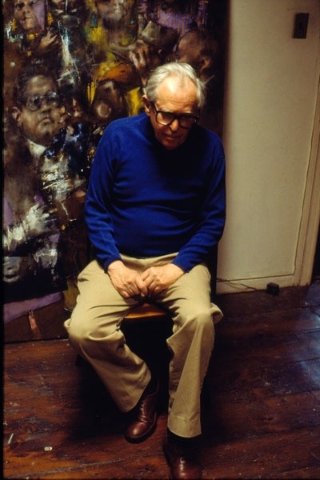

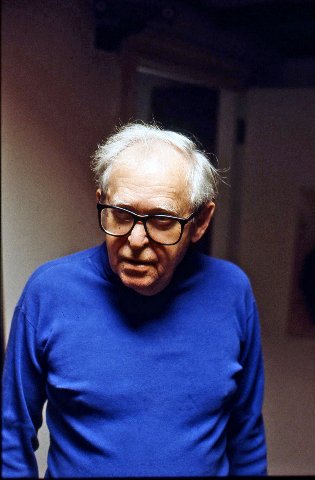

After a laspse of decades Levine and Bloom were reunited several times when filmmaker David Sutherland was filming “Feast of Pure Reason” which was released in 1986. I spent a lot of time with Levine and met Bloom when David, and his then wife Nancy, were working on the project.

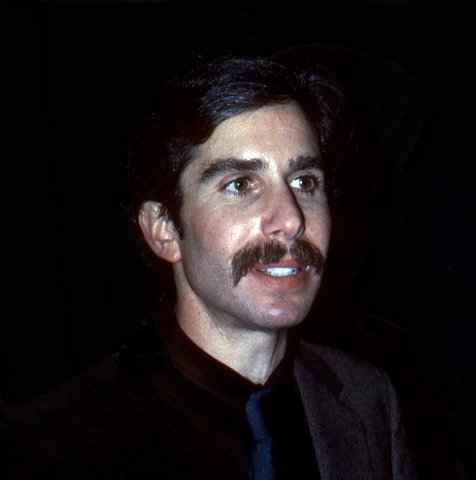

The irascible Levine, noted for his mordant political imagery, didn’t like critics but tolerated my presence. He sat for an interview which I recently published. With amusing hindsight Sutherland told me that Jack liked me because I am Italian. Though he didn’t like that I am a critic.

After films on the artists Levine and Paul Cadmus (“Paul Cadmus: Enfant Terrible at 80”) Sutherland developed long form documentaries for Frontline on PBS. His first “The Farmer’s Wife,” shown on three consecutive nights, was a hit with 18 million viewers.

We connected recently to discuss his work and unique approach. With several films averaging five years each to make, over the past 20 years, he has created 21 hours of film. As he stated, you’re an old man by the time you finish these projects.

Charles Giuliano Do you still live in Newton?

David Sutherland No. In the last year I’ve moved three times. Since I lived in Newton I’ve moved five or six times. It’s been a long road. Now we are living in downtown Natick. We’ve been here for about two months.

My mailing address is the same. I’ve had that mailing address for about 30 years because I have a studio in Waltham. It’s near where I used to live and right on the way of how I get there. It’s right off Route 9. It’s very convenient and cuts through the hills.

CG And Morgan?

DS I’m a grandfather. He has two kids. My daughter Lee has a son. She’s been in San Francisco for twenty years. I was just out there visiting her.

The other update is I had a hip replacement several months ago and I’m walking three to four miles a day. I found the right person to do it and worked hard. I was walking about four hours after the operation.

CG How old are you?

DS In my early 70’s.

CG I’ve got a decade on you.

DS From what I read you’re everywhere. I read your stuff but am always running late on whatever I’m doing. I’m still in touch with Linda Poras and I help her daughter as executive producer on a couple of her films. We stay in touch.

I almost came out to see you in Western Mass. That was six months ago that I wrote to you. I used to go there fairly often.

All the stuff about (Hyman) Bloom it was just yesterday when you sent me one of those pictures. It seems like another age. Occasionally I’ve heard from Aponovichs (artists James and Beth Johannson). But I haven’t seen them in years.

CG For me your narrative begins with the story of when the tire store burned down. After that it was don’t tread on me.

DS It’s still very relevant. Even my dealings with Frontline at WGBH came through Peter McGhee the head of programming who was a fan of the Cadmus and Levine films and he introduced me to David Fanning the executive producer of Frontline when I was working on “The Farmer’s Wife.” You could say that film was sort of an arranged marriage with Frontline that has lasted a long time. And I met Peter through Rebecca Eaton, the Exec Producer of Masterpiece Theater, who used to buy tires from me. I am still close friends with Peter and in touch with Rebecca. A lot of people from those days were really important to me. You as well in many, many ways. I haven’t heard from Jack’s (Levine) daughter in a while.

I had a retrospective at MoMA in 2007 or 2008. They showed fifteen hours of my work. Levine was in the audience and he was pretty old then. (1915-2010) He had a chest cold at the time but told me that he liked the film even better now.

There was a show at the Benton Museum and Bloom had some work there.

(The William Benton Museum of Art is located on the University of Connecticut's main campus in Storrs, Connecticut.)

They showed the Levine film and had some Bloom work on display there. I went there with the Linda Poras. I thought you were there but I misremember. Those days and the barbecue, I remember vividly.

I vividly remember your photography show in the South End (Akin Gallery). That was the last time I saw you.

CG As I recall your first film was “Nancy Skating” which you showed to me.

DS That was one of my early films. I made a film called “The Princess Who Couldn’t Stop Eating.” It was a fairy tale that Nancy wrote. That was a short clip and she was a very good roller-skater.

I remember being in your amazing basement Cambridge apartment.

(University Road noted for my legendary Alice Cooper party.)

CG Have you seen the Bloom show at the MFA? (“Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death” curated by Erica E. Hirshler)

DS I haven’t for a couple of reasons. I finished a film in April and was out of town. There were engagements I had to be at and then I was in California. I traveled quite a bit then we moved. Then with the hip surgery I wasn’t mobile for a while. I haven’t seen it but it’s still there. Correct?

CG Through the end of February.

DS So I am planning to see it. I see that Stella Bloom is still alive from your pictures.

CG Those images were taken a long time ago during Hyman’s opening at the Brockton Art Museum.

When you were filming with Jack how often did you see Bloom?

DS About three times. When Jack came to Boston he had business with the printer Herb Fox. He went to the North Shore several times. When he flew in the first time, he wanted to meet with me. I had met him in New York. He took me to see Herb Fox. I had a 2 PM appointment because my tire store burned down. I had to sign up for unemployment. He waited in the line with me in Newton Corner. Because he was on the dole with the WPA he liked that experience very much. It was weird.

That’s all I saw of Hyman. I remember you interviewing Hyman at that barbecue.

CG I spoke with Hyman a couple of times but I wouldn’t call it an interview.

(Stella discussed visiting them in New Hampshire but with conditions. I could not tape record or be allowed to take notes. I didn’t see the point of that. Plus, he was noted for not showing work in the studio. I knew Dorothy Thompson who visited numerous times. Back home she summarized what they had discussed. She wrote about Bloom and was curator of the Brockton show. With the Sutherlands we had dinner with the Thompsons during which I gave her a copy of my scathing Patriot Ledger review of the DeCordova Museum’s botched Boston Expressionism exhibition.)

But I did interview Levine. In the past few years, as a part of legacy projects, I have been dumpster diving through files of documents, slides and negatives. I’m scanning, tweaking and printings creating portfolios for several museums.

In the Levine file I found the transcribed text of a Levine interview. At the time it was research for a feature in Art New England. I typed out the interview and recently posted it to Berkshire Fine Arts. Decades later it holds up and has interesting insights.

DS I read it several times.

CG Jack discussed how the film came out of an aborted book project.

DS The book project with Jack was not how I hooked up with him. Did he say that?

CG Yes.

DS It wasn’t through Arnold Skolnick who did the book on Cadmus, (1904-1999) “Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude.” Jack knew him. After the Cadmus film I was interested in doing another WPA artist. (“Paul Cadmus: Enfant Terrible at 80,” 1986, 60 minutes.)

Tess Cederholm, the fine arts curator for the Boston Public Library, was the executive producer on my Levine film. I was looking at former WPA artists. I interviewed Balcolm Greene even though his work wasn’t what I was looking for.

(I took a train to East Hampton in the 1960s to have lunch with him. I was curating a portfolio of lithographs on Biblical themes for The United Church of Christ. Ultimately, he was not included in the project. We were also looking at WPA era artists.)

I had a list of other possible artists. A lot of WPA artists got in touch with me. I have a lot of footage of these artists. I went to Seattle and have a ton of footage on Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000). It’s on Super 8 and I would make it available to you.

Tess and I want to Seattle twice. Each time we were there for a week. We filmed him and Gwen his wife. They talked about color because she was light skinned and he was dark skinned.

Who was the famous social historian? I met with him and Jacob in Harlem when they talked about the Harlem Renaissance. I hooked up with him through Tess and Terry Dintenfass (gallerists). I knew her very well through Jack.

Tess knew the gallery Jack was involved with. I’m trying to remember.

CG Kennedy Gallery.

DS They had a falling out. He was from Detroit. I didn’t have any problems with them and there were several events. But I never met him (Levine) through a book. There was talk of doing a book but that was through Kennedy Gallery. It didn’t come through me. The only one I knew was Slolnick who did the Cadmus book. He has a company called Imago Design. I still have some of those Cadmus posters if you want one.

CG Would you have done a Bloom film?

(At the MFA Astrid and I attended a screening of the Bloom documentary “The Beauty of All Things.”)

DS I liked Bloom’s mood. When I did the Cadmus film he was a great subject. I story boarded both the Cadmus and Levine films. They were the subjects of documentaries playing themselves. They were docudramas. I had those skills so I could write a film and storyboard it.

Like the opening scene of the Levine film in Fenway Park. I knew the art historian Milton Brown (1911-1988). I had met him several times. So when they were sitting there watching the Red Sox they were talking about Old Master paintings. They were comparing painters to pitchers.

I knew that story because Levine had told me. For that scene in Fenway Park I knew what they were going to talk about. They sort of switched parts in the film. They weren’t following lines. They sort of got things switched up and I would let things roll.

When I did the Cadmus film, even though it was very successful and got on prime time television at 9 PM, it wasn’t part of a series. I wanted to do another art film because I felt I could be bolder in my work. It wasn’t because of Cadmus it was because of me. I just thought I could do a better job. I was looking for a radically different personality. I met all these WPA artists and Levine was exactly what I was looking for.

Aesthetically, Cadmus is a prettier film but Levine was the perfect film for me to do. I did everything that I could possibly do right. When he was talking about his wife, I had women on the set because I knew he would be emotional. (The artist Ruth Gikow, 1915-1982) He would be embarrassed to really let it out in front of the bunch of men.

There were a lot of moments like that, to use his term, when I was at the top of my game.

The major funding of the Levine film was from NEH the National Endowment for the Humanities. Tess was responsible for most of that. She did the grant writing. We got hooked up with somebody at George Mason University who was an expert on the WPA. I got no money from the arts for that film. It was all humanities grants for Levine.

Cadmus funding was all from collectors. Any art money for Levine came from NY. They didn’t like his art but they liked his politics. I got no Boston money. It was all New York and a little from Connecticut and the humanities grant from the NEH.

We wrote another grant for a Jacob Lawrence film. He agreed to do it. I saw him three times total. Twice in Seattle and once in New York.

(I also met with Lawrence in NY and signed him for the United Church of Christ portfolio. He had just returned from Africa. Later he was invited by Mitchell Siporin to be a visiting artist at Brandeis University. But I was living in NY at the time. When I was an undergraduate Siporin had Levine lecture to us about his work. For a time, I was making paintings inspired by Levine and still have one hanging in our loft.)

I used to sketch in Super 8 or videotape. Then I would go back with a crew and storyboards. That’s what I did with Levine.

Lawrence was desperate to be the subject of a film. He was a great artist. Atlanta Public Television got him to commit to do a one-hour film. When he did it, not that he burned me, but I didn’t want to do a film that somebody else was already doing. Basically, they did a half hour film and he was interested in being shot again. But I didn’t want to do it. I wasn’t mad; I just didn’t want to do it. I didn’t have a lot of money. Morgan was going to school.

A guy called me from the class of ’63 at Yale. It was their 25th reunion and that’s when I started doing cinéma-vérité. He was coming to Boston and got my name through PBS. The Levine film was very popular on PBS. I did a film called “Halftime: Five Yale Men at Mid Life” (1989).

CG I interviewed you at the time and wrote a review for The Tab.

DS After the art films I wanted to do something that was more cinéma-vérité. The Yale film was 90 minutes and that got me interested in doing more long form documentaries. That film turned out to be a summer hit on PBS.

Then I started doing long films like “The Farmer’s Wife” which had 18 million viewers. “Country Boys” also took five years to make. The audience for “Country Boys” was 15 million. “Kind Hearted Woman” was also a five- or six-hour film. “The Farmer’s Wife” is in negotiation to be renewed and is still popular. If you go to the Frontline site “Country Boys” is still playing as well as “Kind Hearted Woman.” The last one I did is only two hours “Marcos Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” (2019 Frontline).

After “The Farmer’s Wife” it got easier for me to get funding in co-productions with Frontline. I got a reputation that I could do cinéma-vérité.

“Farmer’s Wife” was a breakthrough for doing that kind of film. I got very interested in closeups where I could hear breathing and sighs from a hundred yards away. I started to define my work as being a portraitist.

I’m not a journalist and have only been a journalist on one film “Kind Hearted Woman.” (Frontline, Independent Lens; Premiere Date: April 1, 2013; Length: 300 minutes.) That was a story about abuse on the reservations. Then her daughter gets abused by her ex-husband while the film was going on. We didn’t know that and then it came out and they went to court. She’s running to Canada to escape the tribe. That’s still on line.

So that changed me. The only other foray I did into making art films was a period when I used to do two films at the same time when I was younger and they weren’t as long. There was a film I did for the National Gallery of Art called “Feast of the Gods” (1990, thirty minutes) which you can see on my website. I did that in Italy.

CG That was the Bellini painting? (Giovanni Bellini and Titian 1514 to 1529)

DS That’s exactly right. I filmed it in Venice and Ferrara. I didn’t write the script. Pat Hills liked the film and showed it to her classes. She also used the Levine film.

When I was away on location, they were supposed to use the Lawrence footage at Harvard. I couldn’t find it because it was in storage. I have it now but nobody then could access the footage.

The guy who met me in Harlem was the social historian Kenneth Clark. I don’t mean the British art historian. He met me with Jacob in Harlem and they talked about the Harlem Renaissance. I shot footage of that.

To answer your question. Other than “Feast of the Gods,” where I needed extra money because I was doing another film, I did that job for the National Gallery of Art. It was interesting and I had the skills to do it. I had Joe Seamans who was cinematographer for the Levine and Cadmus films.

Just to be complete I did a film on the WPA artist William C. Palmer (1989 sixty minutes). He had been with Midtown Gallery and I did it through D. C. Moore Gallery. It was on PBS sporadically in towns here and there but not with a national broadcast.

So, when I think about it, I did do a lot of art films. The National Gallery film came to me through another filmmaker who knew that I did art films.

CG For many reasons there is now more interest in Jacob Lawrence than most other WPA era artists. Would you consider pulling together the material you have?

DS It was sketching footage so it is not up to broadcast quality. Historically, for somebody like you. There was a show at the Met about Jacob Lawrence and I tried to contact the curator because I thought they would be interested in some of the footage. I know he has a gallery in Seattle or did. I had been in touch with them but not in years. Terry Dintenfass represented him and I knew Bridget Moore from D.C. Moore Gallery. She used to be Cadmus’s gallerist and then Levine who she still represents. She is a friend and I talk to her perhaps once a year. It used to be Midtown/ Payson Gallery. When Cadmus left Midtown Gallery and Levine went with D. C. Moore.

Essentially, the footage I am telling you about wouldn’t be broadcastable. But archivally it’s beyond a dissertation. You have the two of them sitting there talking about living in Louisiana and skin color. She’s light, he’s dark, and the WPA. They’re talking in a really closeup personal way. Lawrence was amazing. Nobody has footage like this. I’ve seen the Atlanta piece.

The footage is not something that I could present. Somebody could transfer it and show clips. In that context it would be fascinating.

CG What about Pat Hills who wrote a book on Lawrence?

DS I contacted her a couple of years ago. But she was moving to NY (Brooklyn) and hasn’t gotten back to me.

Who is the guy at Harvard who had all that stuff happen to him? I did a film on Melissa Franklin the first tenured woman in physics at Harvard. She’s Canadian and friends with a guy who is a black social historian who I met at her place.

CG Do you mean Cornell West or Henry Gates?

DS Yes, Gates. He’s the one at Harvard that wanted the footage that I couldn’t put my hands on at the time. He got in touch with me through Pat Hills and she was pissed at me. But I was out of town and couldn’t help them.

Then I was going to give the footage to that African American place in Roxbury.

CG Do you mean Barry Gaither and the National Center for African American Artists?

DS When I called them it sounded like the place was going under. Then I spoke with Virginia Mecklenburg (senior curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum). About eight years ago she showed Levine and Cadmus back to back at the Smithsonian. It wasn’t my idea. They contacted me about doing it. That was a huge event. For film it was packed. I believe it was connected to a celebration of the WPA.

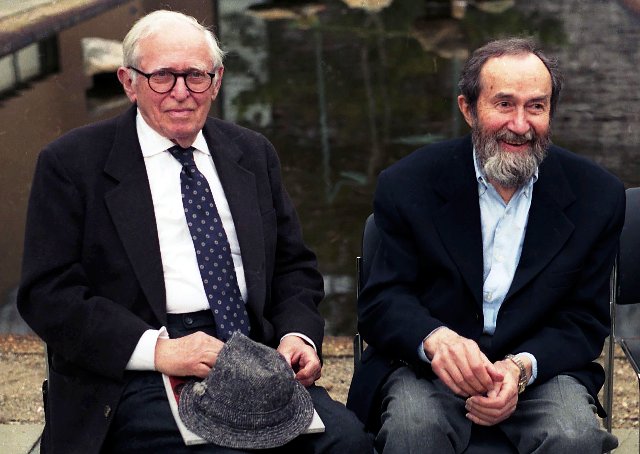

CG Let’s get back to Bloom. There’s enormous interest now that the MFA has finally done a show. It’s a turning point that the museum has finally recognized one of the Jewish artists of Boston. That said they are only interested in Bloom and not in Levine. How is that possible as they were so intimately connected with an unique common education through Harold Zimmerman and Denman Ross when they were teenagers. Borrowed from Harvard the exhibition has juvenilia by Bloom but none by Levine although they were working side-by-side. The Fogg Art Museum had a number of drawings by both of them. They were being taught to draw from memory and imagination.

Give me your impressions of them when you went with Jack to visit Hyman. You say there were three occasions. Did you visit the studio in New Hampshire?

DS I once did. I never really spoke to Bloom as an interview. If I meet two people I’m much better one-on-one. He spoke in such a mellow manner that Jack always seemed subdued with him. Of all the people I met with Jack, and I met many of them, he could be irascible. He could be very outspoken or totally charming. With Bloom Jack would come down and be at Bloom’s level. They would both be very mellow. Jack had great regard for him.

I was blown away by Bloom’s work. I saw a lot of it at the Benton Museum. They had drawings. Also, I saw Bloom’s work at the Danforth Museum.

CG That was the Katherine French exhibition of rabbis.

DS It’s like everything you’ve written about Bloom. He was really brilliant. His social issues stuff I never got to the core of it. If I read about Bloom it’s an insight to me. I’m not qualified to talk about him because we never spoke on an intense one-on-one level. He liked the film and was very courteous. They spoke a bit about Zimmerman but Denman Ross was different. Jack used to say that his color schemes and theories of painting were “as complicated as the eye of a fly.” That’s a direct quote as I’ll never forget that.

Jack basically stopped drawing. You know that? He would draw in oil (on canvas) as you see in the film. He would sketch. Agnes Mongan said that too.

(Agnes Mongan, 1905-1996, was curator of drawing and served as director of Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum.)

He would never sketch and leave drawings around because (when he was young) they sold all of them without him knowing. So, Jack would never draw after that. I have a fish or something that he once drew. He was eating fish. What I’m basically saying is that Bloom’s feelings about them (Zimmerman and Ross) were very similar but different.

It seems to me that Bloom could have been as difficult as Jack. Perhaps more so. It seemed that he had an unbendable will. Is that accurate?

CG Very accurate.

DS You could sense that about him. He was very powerful.

CG Bloom was passive aggressive.

DS That’s very accurate. I was never uptight around him. Being with them was so interesting to me. I once wanted to film them together because I saw how Jack was with him. Jack was a real fan of Bloom and thought he was a great artist. He also really, really liked him. You could see that and it was genuine.

If I had done a film on Bloom, and I don’t think he would have been interested, my approach would have been very different from all the other films. I’m not sure what it would have been. Of all the WPA artists that I met, and there were many, Bloom was a whole different trip. It’s like if you were around during the Renaissance, and ran into one of those people. Bloom was from another planet.

That’s how I saw him and he had a great mood. I’m not saying he was easy but he had very strong vibes.

CG Is it true that they had not been together since Jack left Boston, after mustering out of the army, and moved to New York in 1946? What role did Stella (Bloom) play in bringing them together?

DS She played a huge role. Jack really liked her. He thought she was really nice and brought out the best of Bloom. She got along with Jack so that was the bridge. If Bloom was living alone, and I don’t know his history before Stella, but if Jack and Hyman were on their own, I don’t think they would ever have gotten together. It happened because of her.

Levine had come to Boston to see Herb Fox and I was there at least three times. He had seen Bloom once. I think he had an invitation because he had been in touch with her or looked up Hyman. I don’t remember how it happened. I wasn’t around. It happened from New York. He wasn’t with me when they set up that meeting.

I remember that they said that they had not seen each other since 1946. That came up. I don’t remember 1946 but I remember that Jack told me in the car that they hadn’t seen each other. I think I remember you saying that and you were there when it came up.

Was Bloom at the DeCordova’s Boston Expressionists show?

(“Expressionism in Boston: 1945-1985” curated by Pamela Allara, Lincoln, MA: DeCordova and Dana Museum and Park, 1986)

CG No and I don’t remember Jack being there. Bloom didn’t attend openings. But he did at Brockton for the Dorothy Thompson exhibition. Jack came from New York so I got rare photos of them together. I don’t know if there are images of them together as teenagers.

Do you have insights as to why there is interest in Bloom but none for Levine?

DS I remember talking about that with Kennedy Gallery’s Martha Fleishman who took over running the gallery from her father. I had conversations about that with Milton Brown and Tess Cederholm. It was sort of like a lot of people thought that Jack alienated a lot of people.

But that’s not a strong enough reason because you can say that about a lot of people. Jack used to say that people didn’t like his Judaica. Bloom did that series with rabbis. But I don’t think that was the reason. A part of that is how Jack is regarded in Boston vs. New York. Jack’s work is in the Whitney, Met, Brooklyn and MoMA. A lot the museums got paintings for nothing through the WPA. MoMA has a lot of his work.

CG They have three paintings.

DS The Whitney has “Gangster’s Funeral.” There are several museums in Connecticut that have his work. His work is in a lot of major collections because we filmed it. There’s one in Tel Aviv. Kennedy Gallery did a good job of placing his work. But he went out of style fast. In the long run some people just think that Bloom is a better artist. It’s a matter of taste. In his mind Jack became out of style. And maybe he was. I don’t know who owns “Daley’s Gesture” (1968) but he was doing that for Time Magazine. It’s the one where Mayor Daley cuts off the mikes. His work ended up in Chicago. There are several works in the Benton Museum. His work is in a lot of museums.

CG But not adequately represented at the MFA in his home town. The Danforth Museum has a mandate to show and collect Boston Expressionism, but other than works on paper, they do not own a painting.

The question is which museum in Boston would be willing to do a major show of Levine’s work. Pat Hills told me that there were plans for a show at the Boston University Art Gallery but that the project fell through.

DS The Hirschhorn Museum owns three pieces.

CG When I talked to Jack there was the sense that he didn’t have a lot of money. Other than prints, he sold at best perhaps one painting a year through Kennedy Gallery. They even discouraged him from doing large editions of prints. That was part of why he left the gallery.

DS He owned a house near the Village. It was a red brick house with a couple of floors. There was an apartment downstairs which he rented to a well-known woman sportscaster. He was comfortable with pensions and social security. His house was paid for and he got rent. So, he was pleased with where he was at. I can’t say that he was wealthy but he had no financial problems.

CG You liked his late work like “Sinatra in Vegas.”

DS It was not that I liked every piece. I was trying to get a likeness. His personality. It’s even the same in “The Farmer’s Wife.” If you have met the people, the protagonist, how accurate do you find it? Meaning their mood. I’m always trying to capture their soul particularly in their later work. I captured their mood including Cadmus. I just thought I could have done better work.

I divided it into their careers, them with other people, placing how I saw them historically, but I ran it by them. In the art films I have what I call homes.

If you see them on a diving board it’s stands that I put up in the Gardner Museum. I had a platform for him to be in front of Titian’s “Rape of Europa” talking about the painting. The viewer might not know the painting but it was among his favorites. When you see him wearing a suit in front of that he’s going to talk to you in a certain voice.

That’s what I was going after. Each place, Jack in Fenway Park, it’s him with another person. If he’s an art historian he’s sitting in front of Titian’s “Rape of Europa.” If he’s painting, he’s in his studio. Gradually, all three homes in the film weave together. Elliptically, until at the end he’s touching up the painting (portrait of his daughter) which you saw at the start of the film.

If he’s in the studio painting a portrait of his daughter then you are going to be aware of him as Jack the painter.

CG Why did you not include any footage with Agnes Mongan? Of the time I spent with you a highlight was the day we were at the Fogg looking at the early Bloom and Levine drawings.

DS That and the story with Denman Ross. I thought they were great. Sometimes when making cuts in a film including that material made it too lopsided about his early career. I’m trying to do a portrait of him, the person, and the life. Historically. I had to deal with the Judaica; the social issue paintings. He had three different types of paintings.

Whether right of wrong, when it came to the early career, I made the choice to condense it. Mongan’s footage was rather stiff. She was fascinating but stiff on camera. He was very reverent to her. The footage was interesting but didn’t hold up to the rest of the film.

I had the same problem with the Cadmus film. He was Lincoln Kirstein’s brother in law. He brought over Balanchine and started the New York City Ballet. When they tried to sell the ballet to America, they had this thing called The Ballet Caravan. They did a lot of plays when Balanchine came over. They did scenes from America and Cadmus painted a lot of them. The footage was fascinating and it would have added dimension because Cadmus painted a lot of the sets. But it weighed down on the story and I discussed that with him.

I didn’t ask for their approval but when it came to cutting it down either it didn’t work the way that the rest of the footage did or it slowed it down. My films are usually fairly ponderous as some people say. I’m not saying that I think they are. They didn’t work (Mongan and Kirstein). In the Cadmus film I still regret that I didn’t use The Ballet Caravan. But I understand that decision.

In the Levine film what you said about Agnes Mongan is right. What she said about him was fascinating. But the two of them together didn’t hold your interest. She wasn’t very comfortable with the process. She was very welcoming to us. But she was stiff on camera and maybe that was my shortcoming.

The Cadmus film was originally 64 minutes. The TV version was 59. Which do I like better? The TV cut. The egg tempera paintings scenes were great. One of them played in the window of a NY store. It was a scene of him with an egg yolk in his hand which they looped.

CG Was it Tiffany?

DS No but he did do some Tiffany eggs. I also had a great scene with Malcolm Forbes who gave him money but I didn’t use it.

CG How much footage was there with Agnes Mongan?

DS I don’t still have the footage. There was probably about twenty minutes. With Mongan I would have gone back and filmed it but we felt it didn’t hold up. It’s just how she was with Jack.

CG So it was just a sketch.

DS That’s exactly right. Just to let you know. Did I find it interesting? I found it fascinating. If I was doing more of a feature film, those scenes with Milton Brown, what happened was to be able to integrate. If it was a more traditional documentary I could have just cut from Levine to Mongan talking about his work. But I didn’t do the film in that style.

CG To digress, there is the large phenomenon and issue of the Boston Expressionists, who they influenced, and their role in the history of 20th century art. There were Jack and Hyman as a pair and Karl Zerbe who emigrated from Germany as an adult. It is unclear what relationship they had to Zerbe, particularly as Jack left Boston in 1946. So is the assumption that they were the Boston Expressionists even accurate?

Bloom evolved as a visionary and Levine pursued social commentary. Neither of which entails expressionism other than in the broadest terms. It may better be applied to Zerbe who evolved from it in Germany. Early Bloom is linked to the emergence of abstract expressionism. He was admired by de Kooning and Pollock but did not conform to the agenda of the New York School. Zerbe directed the programming of the Museum School.

The next generation included Arthur Polonsky, my teacher at Brandeis. Henry Schwartz taught at the Museum School and David Aronson became head of the School of Fine Arts at Boston University. Philip Guston commuted from NY to teach there and influenced Jon Imber and others. Gerry Bergstein came from New York but became a part of this tradition at the Museum School. That was the thesis of the DeCordova show but Pam Allara got a lot of things wrong.

DS I went with Jack to BU meeting with Aronson, who he admired, and other faculty.

CG I was there that day. The MFA displays a sculpture and painting by Aronson as well as Levine (a minor work), Bloom, Zerbe and Guston.

DS Aronson came to several Levine events. I believe he had a daughter whose husband was a musician at Berklee (College of Music). Jack’s daughter Suzanna went to BU art school. Jack liked Aronson a lot.

CG A question is why the MFA has ignored an important chapter in 20th century Boston art. The argument is based on historic issues of anti-Semitism and racism. That has become a hot button issue for the museum and is fueling motivation for change.

The Bloom show is an isolated and arguably strategic measure. Nothing appears to be on the table for other Boston artists they taught and influenced, individually, or as an overview. If Jack and Hyman evolved as virtual twins how can the MFA show one yet ignore the other? It promotes lopsided, revisionist art history. What of their long shadow over generations of Boston artists?

DS I hear what you’re saying but stylistically they are so different. It could be with certain people at the time, and I can’t say it for today, it could be anti-Semitism. Jack blamed it on stylistic change. He was out of style. From what I heard from him he never framed it as being anti-Semitic.

He was still a Red Sox fan as you know. He loved the Gardner Museum. Every time he came to Boston he wanted to go there. He liked artists like (John Singer) Sargent. He liked a lot of artists. He didn’t like abstract expressionism. By and large he liked being from Boston even though he became a New Yorker. He was very proud of his Boston roots. But there was nothing for him here and maybe for a lot of reasons that was the case. Going into the army, and then moving, a lot of things just worked out better for him in NY.

At the same time, it’s true that there has been absolutely no interest in his work. Except for the DeCordova when they had that show. There were some art historians there that really liked his work. By and large, Tess Cederholm would say the same thing, there was not a lot of interest in his work in Boston. I couldn’t raise five cents in Boston when I was doing the Levine film.

CG Is there any interest in Levine today?

DS I’m out of touch. I read about and go to shows. More out of town than here but in general there’s still interest in Levine in New York. I have the Levine film on Vimeo. I still hear from people who are interested in his work. It’s at a lower but not lowest point. When I did the film there was still interest in him. That’s since waned but I’m more out of touch.

CG Levine is perceived as part of the 1930s social realist movement when in fact he is of the next generation. He was a WPA artists during that era but very young. Because of the “Triumph of American Art” and the ascendancy of abstraction expressionism, and the New York School in the post war era, both regionalism and social realism came to be regarded as provincial and reactionary. There was a shift to the avant-garde as “America Stole the Idea of Modern Art.” (Irving Sandler and Serge Guilbaut) That left Levine out in the cold with Bloom regarded, for a time, as more progressive. Then Bloom appears to have self-selected out of the mainstream.

DS You’re right that, of all of those artists, there has been the most interest in Jacob Lawrence. He had a relationship with the jazz bass player Milt Hinton (1910-2000). By coincidence I shot footage of Hinton. I was going to do a film on him and I have great footage which I can’t show. I have him talking about being in Chicago when he played with Cab Calloway. It’s amazing footage and Gates would love it. At the same time, they ended up having a show together in Connecticut. Milt Hinton and Jacob Lawrence, can you believe that?

CG Hinton is now well known as a major jazz photographer. As a musician he had access and insight to fellow jazz artists.

(Hinton and David G. Berger co-wrote “Bass Line: The Stories and Photographs of Milt Hinton,” Temple University Press, 1988, and with the addition of Holly Maxson, the three co-wrote “OverTime: The Jazz Photographs of Milt Hinton,” Pomegranate Art Books, 1991 and “Playing the Changes: Milt Hinton's Life in Stories and Photographs,” Vanderbilt University.)

DS I’m sitting on the footage and it’s costing me a fortune. It’s all air cooled. Is the broadcastable? I don’t have the rights. With Lawrence I do have rights. The footage I have, and what they say on camera, is very usable. But it would be more for scenes of someone doing a film on them. They could use clips but there is not enough material for me to do a film in my style. What I am saying is that it is very valuable material.

To answer your other question, I haven’t seen any interest. Although I am out of that world but do follow him (Levine) on the web. You can watch the film on Vimeo which I never had until three years ago.

What I am saying is that your take on it is pretty accurate. I have heard of no new Levine shows, anything, even group shows. I’m on enough social art sites and from letters I have received from people who are interested in Levine. They may be art students or somebody from a period who knows the work. Or some graduate student. But by and large I have heard nothing. But I’ve been very aware of interest in Jacob Lawrence.

CG Did you make the wrong choice?

DS I chose subjects that interest me. One might say that films I have made are about people who are not that famous. “The Farmer’s Wife” “Country Boys” about two boys from Appalachia. Why do them? Why do a Native American woman? The issues come out of the person. For Levine it was the issues he was painting. The social message. The work showed a certain story. Then it changed. Some of the stuff I was less interested in, but became more interested in, was the Judaica. You asked me about his later work. (“Sinatra in Vegas”) I didn’t always like it. When I look at his mezzotints and the late prints, I was amazed at how good they were.

(A Levine edition of small prints was created as gifts to people who supported the film. I am proud to own one.)

I didn’t appreciate them as much at first. It’s like when I look at Bloom’s drawings, not that I know them well, but I’m pretty blown away.

The reasons why I chose my subject matter would not be by popular demand. Which has probably hurt my career. I’m being honest.

CG Back in the day, before you transitioned into long form Frontline documentaries, you told me that you wanted to do dramatic feature films.

DS That’s a really good point. “The Farmer’s Wife,” which had 18 million viewers became one of the major hits on PBS. It went on the night that the Clinton tapes were released. It had no major sponsors. It went up against network sitcom premieres and Monday Night Football. By the third night it was the biggest thing on television. It was three nights in a row and had 18 million viewers.

After that I got some possibilities. I turned down a chance to do a commercial film for a major international company. I was burned out and didn’t want to do it. I could have made a quarter million dollars for a twenty-minute film. I’ve done stupid things. It wasn’t just because of genetic engineering of crops.

I was brought out to Hollywood and had an agent. Then I got a grant to do a film in Eastern Kentucky “Country Boys.” These films (“Farmer’s Wife”) took five years each. “Country Boys” took seven.

In the last 20 years I have done 21 hours of film. Six with “Country Boys” and six and a half with “Farmer’s Wife.” Five hours for “Kind Hearted Woman.” I did two hours on this last one. (“Marcos Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”) They’re long form documentaries. By the time you finish them off you’re an old man. All of a sudden, it’s 20 years later.

I wanted to do film noir. I optioned a couple of pieces and had an agent representing me. I optioned a Joyce Carol Oates short story. I started to realize that what I did on “The Farmer’s Wife” touched so many people. I thought I could do great film noir. With what I was doing, these up close portraits. Like a farm family, will they stay married? Giving you a sense of what it was to live in the ‘90s. With “Country Boys” the hopes and dreams of two boys during the last three years of high school. I’m doing a portrait of America. I realized that right or wrong, and I don’t regret it. Because my career didn’t take off until I was forty years old. I thought that I was doing something special. I chose not to do it. (make a feature film) I did have a chance to do a feature but gave it up to make “Country Boys.” I thought it would be more special. And I know I could have done a really good film noir. A film like John Dahl’s “The Last Seductions” or “Red Rock West.” That was the type of film I wanted to do.

With “The Farmer’s Wife” I followed it for three years until she turned thirty. I started the film when Juanita was about 26. So that was four years. “Country Boys” took longer. I had four subjects which became two. “Kind Hearted Woman” the woman ended up shooting herself.

(Robin Charboneau was a 32-year-old divorced, single mother and Oglala Sioux woman living on North Dakota’s Spirit Lake Reservation. The film follows her over three years as she struggles to raise two children, further her education, and heal from the wounds of sexual abuse she suffered as a child.)

There’s a lot of speculation and it could have been done by someone else. That film took five years.

CG When you’re on location for that long how do you sustain yourself? It seems like such a disruption of your personal life.

DS We used to live/ work together and later on not. When I did “The Farmer’s Wife” we stayed out there once for three or four months. The people in this one town Bladen, Nebraska, when we were out there, never thought we would finish the film. They used to refer to us as “the idiots.”

(Bladen is a village in Webster County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 237 in the 2010 census.)

Before the film came out Senator Bob Kerrey, who was involved with Deborah Winger, and Senator Chuck Hagel the republican, introduced the film in Congress. Juanita Buschkoetter (“The Farmer’s Wife”) was there to testify regarding the state of farming in America. There were 700 to 800 people in the Watergate hearing room. The senators said to me that “The people of Bladen, Nebraska want you to know that you can run as a democrat or republican, either way, we will endorse you for Mayor. The town will endorse you to run for Mayor.” I was that popular.

For this last show I was flying to Omaha, Nebraska. I hadn’t been there for years. The last time I was there was at the press club. I’m flying out and at a gate in Chicago. You take international flights going to Omaha. I don’t think there are any direct ones from Boston. In Chicago I’m boarding a small plane. People are saying goodbye to friends. I was talking with some of my crew who came to have lunch with me. Somebody said “Where are you from with that accent?” I have a strong Boston accent but not like the Kennedys. I said “Where do you think I’m from?” They said “I don’t know.” I said “I’m from Boston” and they started to laugh. I said you can laugh all you want but I’ll have you know that I could have been Mayor of Bladen, Nebraska.

I was talking with Juanita just before Christmas. I keep in touch with her and just about all of them.

What’s I’m basically saying is that the time spent on those films was a lot. So yes, it’s trying. It wasn’t so much just being out there. Sometimes you hit a film or two where there is trouble. Or you’re too tired and things fall apart.

CG So that’s what happened.

DS Even with the success of those films you don’t get a fat head. The other thing that’s been hard for me, and I probably told you this, is that I’m dyslexic and I didn’t know it until later.

In the second grade we moved and I had almost lost my hearing. Where I lived near Newton Center, in the elementary school they taught reading by memorization. When I moved to the south side of Newton, which was all farm land at the time, I missed six months of school with illness and almost went deaf. These are the formative years. At my new school they taught by sounding out. The teacher didn’t believe me and I ended up wearing the dunce cap. That definitely had an effect on me. I was a shy kid but rebellious. It impacted by looking at yourself in the mirror in front of the class and how do you look. It was one of those cone head ones and I still vividly remember that. I didn’t look in the mirror until I was 40, by which time, I must have blocked it out. You look like a fool. It’s either denial or inured. There are certain things like that.

There are periods when you have to get through hard times.

CG For me the time you spent in rural American recalls the Walker Evans/ James Agee collaboration which started as an assignment for Fortune Magazine and evolved into the book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” (1941).

DS I read it and was fans of them both. Someone told me later that when making “The Farmer’s Wife” I had lived with 52 families until I found the right one. You’ve got to be a low-grade moron to do that. I’m not comparing my work with James Agee or Walker Evans but when I read their experiences living with farmers and all that stuff I felt, I can’t compete with you with my art, but some of my stuff is pretty good. But I feel pretty good about spending time with you (farmers) and following a subject. I was fortunate to even find a subject. In “The Farmer’s Wife” I found two subjects. It was raining and I stayed on the Buschkoetter farm and dropped the other subject. Which, on paper, was a much better story. But it wasn’t a better story in real life. That’s a true story. 52 farms and still I can’t believe it.

CG What’s next?

DS Nothing. I just finished a film. Had my hip replaced and have a couple of ideas that I might be interested in. I’m trying to figure it out and am about to go out on a scouting trip.

CG Are you solvent?

DS I’m ok. I’m not a member of the director’s guild but I got some advice. The later films became so talky. I had done a film that I should have gotten a writing credit for. But I wasn’t a member of the writer’s guild. So, I couldn’t take writer’s credit. After that I joined the writer’s guild. I was allowed to join. I worked in Hollywood as a foreign film critic. It’s a long story. I ended up being a member of the writer’s guild. I was doing long form and the more hours that you write, which is not why I made them long, I get some kind of pension from the writer’s guild. But I’ve never been a member of the directors’ guild.

You’re a writer. The stuff you sent me (Bloom review and Levine interview) I read two or three times. I really liked what you wrote. I always liked your writing. No, seriously, that’s why I followed you when I realized what you were writing about. I’ve always been a fan. I wish I could have helped more with Bloom but I’m not going to lie about it. And Stella had a role in that dynamic. Jack played to women more.

CG You were so generous in allowing me access on that project. Hanging out with you guys I got to snuggle up to Jack here and there. But right from the get-go he made it clear that he had no use for critics.

DS He didn’t like critics but you had one thing going for you. I knew this from him. You were Italian.

CG What does that got to do with it?

DS He loved the Renaissance and Italy. He knew you knew something about that. You know, he was very irascible. That’s an understatement. But he did like you. I’m letting you know that posthumously. But, you’re right, he didn’t like that you were a critic. He did like you, or I would have said to you that he didn’t, if you follow what I’m saying. You should know that. And I know that you weren’t the biggest fan of all of his work. I’m not saying this to be overly nice. But I’m giving you an accurate depiction.

CG I appreciate that but our commonality is that we have never made the right career moves. I’ve spent my life backing the wrong horse. We have gone with our gut and heart. That means pursuing passion and what challenges us rather than what will play well for readers and audiences. Which is why the success of “Farmer’s Wife,” with its hardships and sacrifices, is all the more remarkable. We have resisted the easy path of doing portraits and projects about people who are already famous. This dialogue is manifestation of that. It’s also apparent in the transparency, depth and honesty of what we have discussed. It has taken a lifetime of work and commitment to have this conversation.

We back the dark horse because that story has more to say about the run for the roses.

Interview with Jack Levine.

Review of MFA exhibition Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death.