Song for 2001:A Space Odyssey, Just Released

52 years later

By: Jessica Robinson - Jan 13, 2021

Mike Kaplan is a producer, documentary director, actor, award-winning poster designer and marketing strategist. He is known for producing The Whales of August, (Lilian Gish’s last film.) A Clockwork Orange, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead, Robert Altman’s Short Cuts and more.

In addition, he is a collector of historic movie posters that have been exhibited in Museums from Los Angeles to Jacob’s Pillow.

He is also a songwriter.

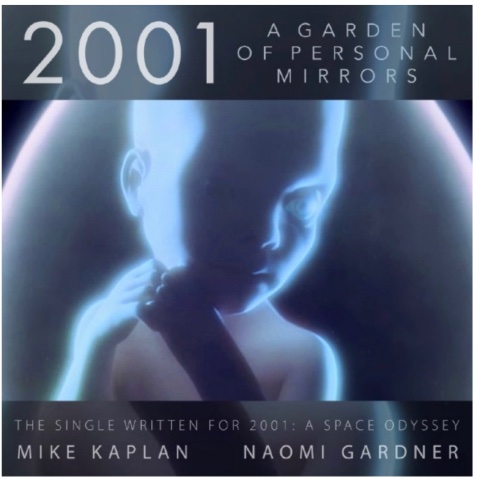

On October 30th, 2020, Wave Theory Records digitally released, for the first time ever, 2001: A Garden of Personal Mirrors, composed by Mike Kaplan for the groundbreaking, 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

1968 was a tumultuous year. It was the year of the Prague Spring, of student protests over the Vietnam War; it was the year that ushered in sexual promiscuity and recreational drugs and witnessed the assassinations of both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. It was the year that Apollo 8 orbited the moon.

It was also the year that 2001:A Space Odyssey opened….. to a sea of criticism.

Pauline Kael wrote, “it’s monumentally unimaginative.” The New Republic called it “a film that is so dull it even dulls our interest in the technical ingenuity.” Renata Adler, in The New York Times, wrote: “somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring…and the uncompromising slowness of the movie makes it hard to sit through.” John Simon called it “a regrettable failure.” Arthur Schlesinger deemed it “morally pretentious, intellectually obscure and out of control.” Steven Hunter, in The Washington Post, wrote: “maybe it’s just that I wasn’t high this time when I watched it.”

In other words, in 1968 the critics weren’t getting it.

Fifty-two years later 2001 A Space Odyssey is considered one of the major artistic works of the 20th century. It’s a film that has been ingrained in popular culture. Everyone has heard of the villainous computer HAL, and recognizes Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra” playing over its most memorable scenes.

The movie has won 16 awards, including the Oscar for Best Visual Effects. Not bad for a film that Rock Hudson walked out of exclaiming, “What is this bullshit?”

2001: A Space Odyssey is long (2h 44m,) has very little dialogue and no traditional musical score. It attempts to tell the entire story of the evolution of humankind, from primitive ape to artificial intelligence and the future of mankind’s place in the universe.

The soundtrack is totally iconic, filled with classical music that was initially meant to be ‘temporary.’

In the early stages of production, Kubrick did commission a score from Hollywood composer Alex North, who had composed the score for Spartacus. North was thrilled because he knew there were 40 minutes of dialogue in a two-and-a-half-hour film. He thought “that means I have a blank canvas to write anything I want.” But Kubrick wanted to keep the temporary tracks. He’d fallen in love with the classical music.

North said he could replace those tracks with material that would be similar in mood or spirit. It didn’t work out that way. He could not compete with the greatest composers in history.

North did record his score. And had a nervous breakdown doing it due to all the pressure. During the recording sessions he had to be wheeled into the studio laying in a hospital bed with muscle spasms in his back.

A lot of people thought his score was good.

Kubrick did not.

North only found out when he attended the premiere in New York. Not one piece of his music had been used. What they ended up using, was Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” extracts from Gyorgy Ligeti’s requiem: “Lux Aeterna” and “Atmospheres” and Johann Strauss’s “The Blue Danube Waltz.”

But the story doesn’t end with North. Ligeti, too, was shocked when he first saw the movie. His music was used, without his permission! (He did ultimately receive royalties, and his name in the credits, which made him a world-famous composer.)

Back to Mike Kaplan’s odyssey.

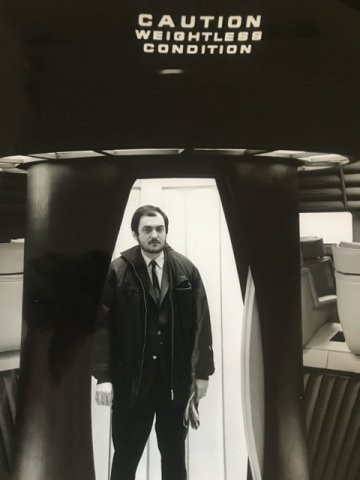

Kaplan was, in those days, the resident longhair in MGM’s publicity department. On the back of the bad publicity 2001 was getting, it was Kaplan’s job to work with the befuddled reviewers and try to explain what they were missing. They weren’t getting “this metaphysical drama that showed the beauty of space, the terror of science, the mystery of mankind was being completely misunderstood,” says Kaplan.

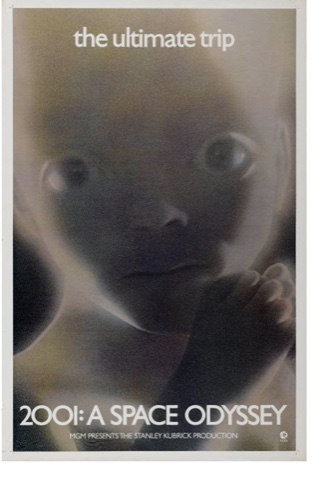

It was, at that time, the most expensive film in MGM’s history (the budget was 12 million dollars, equivalent to 150 million today.)The future of the company rested with the success of 2001. The film’s budget, coupled with the slew of terrible reviews, could have destroyed the studio. But it did not. Mike Kaplan had an idea — to create a marketing campaign, using the slogan “The Ultimate Trip” with the somewhat creepy, baby-faced image of the Star Child, a floating fetus birthed in a glowing placental orb seen at the end of the movie.

The marketing campaign dominated every newspaper page worldwide. It was such a marketing success that even BMW began using “The Ultimate” slogan for their campaign: “The Ultimate Driving Machine.” “That campaign was the turnaround. It sealed 2001’s fate as a cultural phenomenon,” says Kaplan.

Having gained Kubrick’s confidence and respect, Kaplan was spending most days in the War Room on the 26th floor of MGM, continually brainstorming and strategizing about how to creatively maximize 2001’s evolving cultural impact. “The film was the center of my life,” says Kaplan.

The 26th floor conference room was Kubrick’s headquarters — a cousin to the War Room in Dr. Strangelove-with multiple phone lines and enough wall space to hold the dozens of clipboards of every review and article and 2001 ad, in chronological order, whenver they appeared worldwide. Kubrick studied these, intensely, on a daily basis.

One day Kaplan attended a meeting with Kubrick and MGM Records, whose president, Mort Nasatir, was pitching a song, hoping it would be released as a single to tie-in with the film‘s marketing campaign. “The song was maudlin, a terrible fit for the film,” says Kaplan.

Kubrick turned down the proposed song and then, unexpectedly, turned to Kaplan. “Changing tones, he looked at me with his piercing eyes that held you transfixed: ‘I hear you write music. Why don’t you write something?’

“Stanley never asked a question without a purpose. I was shaken — first that he knew about my music, which was a very private hobby, and secondly, that he thought I’d be capable of writing something appropriate.”

“I mumbled, ‘I don’t know what I could do. I lean towards standards.’

His penetrating gaze didn’t flinch. That was Kubrick’s ‘your answer’s not good enough.’

Kaplan quickly realized Kubrick was making a serious request. “I knew it would have to be original, conveying the film’s spirit of symphonic, operatic, transforming structure. Impossible. Out of my league.”

He accepted the challenge.

Kaplan spent the following weeks composing the song. “The song that seemed closest to what I strived for was MacArthur Park, Jim Webb’s abstract, fully orchestrated ballad, performed by actor Richard Harris. It was seven minutes long and broke all the rules for what could be a popular success.”

When he felt he had achieved his goal, Kaplan decided to have it professionally mixed. He invited the singer, Naomi Gardner, to record it, while he accompanied her on piano.

Kaplan then went to Kubrick’s rented home on Long Island to demonstrate his new composition. He was both nervous and filled with excitement.

The only thing Kubrick could provide for the demonstration was an old, crude, antique Victrola. The recording was barely audible on the small stereo speakers. The needle was scratchy. The sound was tinny. A disaster.

Kubrick rejected the song. Kaplan was “crushed.”

Kaplan continued his role in marketing, and went on to work with Kubrick on his follow-up masterpiece, A Clockwork Orange.

During the next four years, from the original release of 2001, through its relaunch a year later with Kaplan’s brilliant, “Ultimate Trip”/Starchild campaign, followed by the release of A Clockwork Orange, they spoke and strategized film distribution daily. They remained in close contact until Kubrick’s death in 1999.

Back to the song.

2001 is infamous among film music aficionados for the way that Kubrick abandoned Alex North’s original score in favor of innovative use of pre-recorded classical pieces that have become synonymous with the movie.

Wave Theory Records’ decision to release “The Single” adds yet another chapter to 2001’s unique relationship with music. Sung by Naomi Gardner, with Kaplan at the piano, 2001: A Garden of Personal Mirrors continues the film’s musical legend.

After listening to A Garden of Personal Mirrors, Arthur Hamilton, composer and lyricist of such greats as “Cry Me A River” wrote to Kaplan: “Your creative connection to that historic film guarantees it a place in the world. It need not be compared to any other song from any other era. It’s from another time and another world, and it should be respected as such. Also, it extends Stanley Kubrick’s reach into the future. And yours.”

Listen to the song here.