Remembering Jeff Beck

Relentless Innovator of the Electric Guitar

By: Steve Nelson - Jan 13, 2023

Growing up a rock ‘n’ roll fan in the 1950s and 1960s, I have seen so many of my favorite performers leave for their final tour in the sky. In ‘59, a plane crash took Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper. In ’70 and ’71 hard living and drugs got Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison. There were many more: Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Bob Marley, Sterling Morrison of The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed, Brian Jones and Charlie Watts of the Stones.

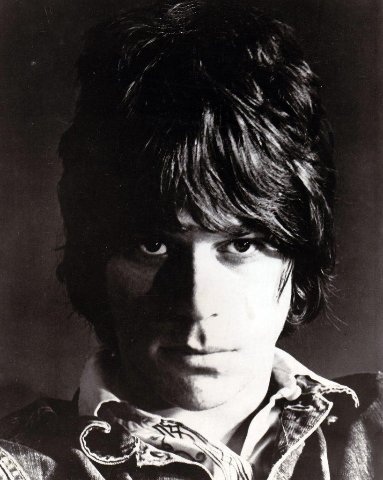

When I logged onto the home page of The New York Times website on January 11 and saw a large picture of Jeff Beck, I knew what it meant before I’d read a word. The plug had been pulled from one of the greatest electric guitar players of all time. Dead at 78 from bacterial meningitis.

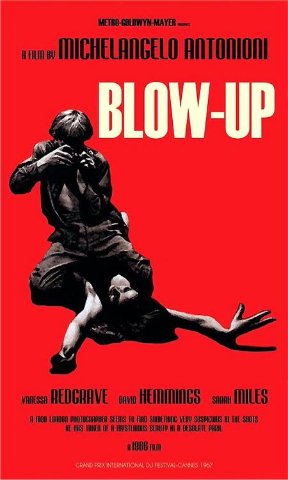

Jeff first made his mark in The Yardbirds, replacing another pretty good guitar guy, Eric Clapton. I was a big fan of the band, but I’d never seen them play, in person or otherwise. Until one day in December ’66. I was visiting New York for a few days, and while reading the Sunday Times came across a large ad for the world premiere that night of Michelangelo Antonioni’s new film, Blow-Up. I’d seen most of his films and didn’t want to miss this one. So on Monday at noon I was in the Coronet Theatre for the first showing of its theatrical run.

When the scene rolled with The Yardbirds playing in a club and Jeff Beck smashing his guitar into a cranky amplifier, I was mesmerized. When the film ended, I didn’t move and sat through it again. It was not the only film I’ve seen twice, but it was the only one I saw twice in a row. I might have stayed for a third showing if I didn’t have to leave for dinner with my parents. They never would have understood why if I didn’t make it.

By the following summer I had a new job: manager of a club called The Boston Tea Party, a psychedelic temple of rock. In seven US tours, The Yardbirds had never played Beantown, despite having a fervent fan base there. Graffiti in the Tea Party men’s room proclaimed “Beck is God.” So when their agent offered me the chance to book the band in April ’68, I jumped at it. Jeff had left the band by then, replaced on lead guitar by Jimmy Page, who’d played second fiddle to him in the version of the group in Blow-Up.

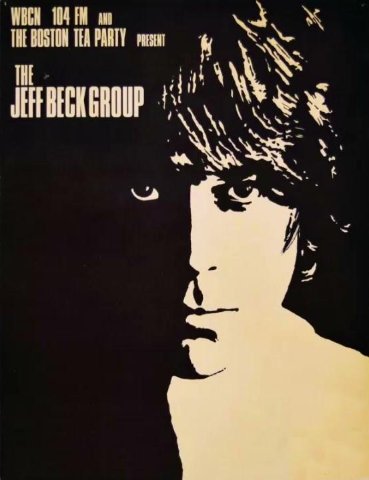

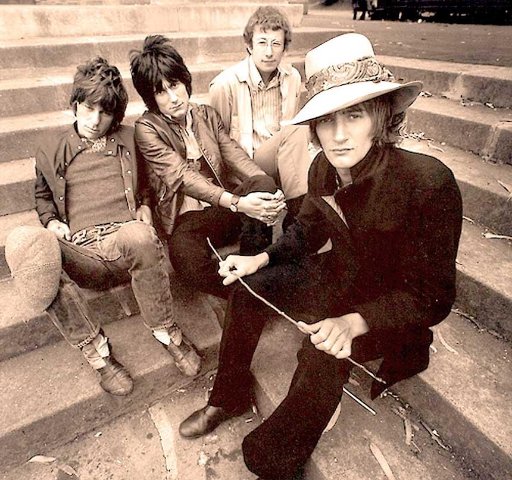

Meanwhile, Jeff had formed his own eponymous band, and on their first American tour, I booked them for four nights at the end of June. I’d been having a disagreement with the owner of the Tea Party, Ray Riepen, over my compensation. He also gave me grief over what I was paying The Jeff Beck Group: $2000. That’s right, $500 a night for Jeff Beck, Rod Stewart, Ron Wood with top session drummer Mick Waller. Are you fucking kidding me?

To promote the show I produced a handbill with a head shot of Jeff on the front – he embodied that British rock star look – with a reprint on the back of a rave review in The New York Times of the group opening for The Grateful Dead at the Fillmore East. They killed the Dead.

Wednesday night we had about half a house, OK for the middle of the week. But I knew what was to come. In the crowd were the local musicians and hip influencers who would spread the word the next day through the grapevine in Cambridge and Boston. Sure enough, the next three nights were packed beyond capacity, with people on line unable to get in.

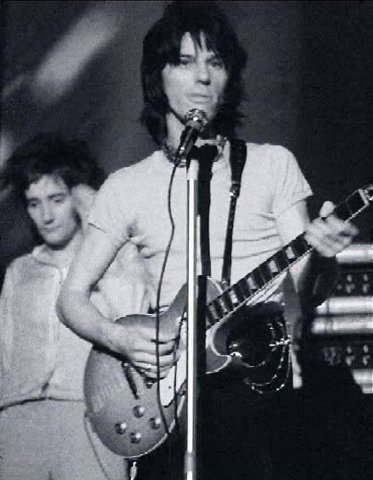

Their Tea Party shows consisted mostly of tunes from their first album due out the following month, Truth. It was a harbinger of the varied styles and influences that became Jeff’s hallmark. The opening cut was a classic Yardbirds number, “Shapes of Things.” The classic English air “Greensleeves,” the contemporary folk tune “Morning Dew,” even the show tune “Old Man River.” Electric blues, with tunes by B.B. King, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, all of whom had played the Tea Party that spring. And Jeff’s signature instrumental “Beck’s Bolero,” with Jeff’s guitar soaring above a Ravel-like beat.

I had to run the club, so I couldn’t sit around and watch the whole show, but over the course of the four days I managed to catch most of it. There was Rod Stewart growling “Ain’t Superstitious” with Jeff, Ron and Micky just whaling it. It was my last weekend as manager, having decided it was time to move on. What a way to bow out. Ain’t that the truth.

After the final show on Saturday night, the band came over to my apartment near Harvard Square. My girlfriend Barbara and I were in the process of moving, our furniture already gone. So we all lounged on cushions on the floor, sipping wine and having a conversation like we were students at Oxford. It’s the only after-show party I ever went to where no one was smoking dope. But the band was high with the success of their tour.

Long after my music biz days I became, among many other things, an inveterate writer of letters to the editor. I’ve had quite a few published in that Holy Grail for letter writers, The New York Times. In fact, I’m probably the only person ever to have two letters published in the Times on the same day. It was in a Sunday paper. One letter was in the News section. The other was in Arts, praising Jeff Beck and recalling his appearance at the Tea Party.

In the Times obit for Jeff, it cited a quote by him in Music Radar, talking about his Fender Stratocaster: “It’s a tool of great inspiration and torture at the same time. It’s forever sitting there, challenging you to find something else in it. But it is there if you really search.” So much of Sixties rock (and beyond) was about wringing new sounds from an electric guitar. No one was a more relentless and creative explorer of that wild country than Jeff Beck.

----------

Adapted in part from Steve Nelson’s memoir Gettin’ Home: An Odyssey Through The ‘60s. www.gettinhome.com