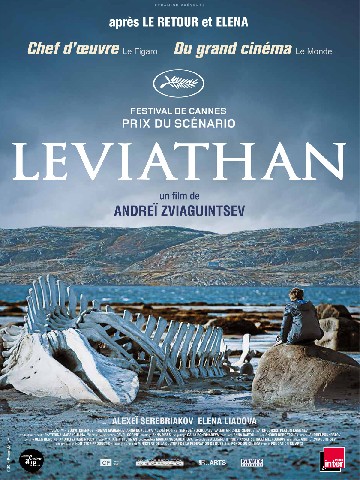

Leviathan by Director Andrei Zvyagintsev

Oscar Nominated Foreign Film

By: Christopher Johnson - Jan 16, 2015

“Leviathan” presents a set of performances locked together with precise cinematography but also delivers a film about something very small and personal, that lingers dangerously close to being insignificant.

Through the film, Andrei Zvyagintsev salvages the story of Kolia, a farmer who is to be evicted from his land by the Barents Sea, as well as his wife, Lilya, and his brother, Dmitri, a lawyer who is trying to help him. The evicter is a ruthless mayor, Vadim, who cares only about pursuing the larger interests of the region in building a communications center on this plot of land.

The producer, Alexander Rodnyansky, has said: “It deals with some of the most important social issues of contemporary Russia while never becoming an artist’s sermon or a public statement; it is a story of love and tragedy experienced by ordinary people.”

Zvyagintsev has a way of stepping back from his films even though he himself had a lot of artistic influence on the film. As in “The Return” and “Elena”, the viewer feels more with one character who is against another protagonist who they often love but feel resentment for at the same time.

Rodnyansky and Zvyagintsev himself have said that the film is a retelling of the Book of Job but it is not definite which character suffers more, Lilya, Kolia, their son, or their relatives. They all seem to suffer. Kolia is the one who completely denies a god. Taken as allegory, the film would show just a classic scenario of a political oppressor being an evil god while the people suffer but the film is much more nuanced than that.

It is a masterfully harsh criticism aimed directly at contemporary Russia. This is the first film by Zvyagintsev to criticize the political powers but the other critical idea that pervades his films is the oppression and status of women. Lilya is in a place where she is so powerless that she has very few options.

The film has a wonderful score by Philip Glass that is used in a keenly uncinematic way that fits the somber, dim lighting and blue-gray color scale. With this film, it is possible to take any still and stare at it, not necessarily finding anything new as time passes but just being in wonder at the composition and the range of colors possible in the blue-gray spectrum.

Very few films have come out like this one in recent years that separate the ethical and artistic issues so succinctly yet combine them at the right moments. Zvyagintsev merits more appreciation and with a Golden Globe foreign language film on Sunday and a possible Oscar, it seems as though his best work so far will get more recognition despite the wishes of Russian officials.