Barenboim Reveals Bruckner at Carnegie Hall

Berlin Staastskapelle Berlin Uncover the Keys

By: Susan Hall - Jan 28, 2017

Bruckner Symphony Cycle

Staatskapelle Berlin

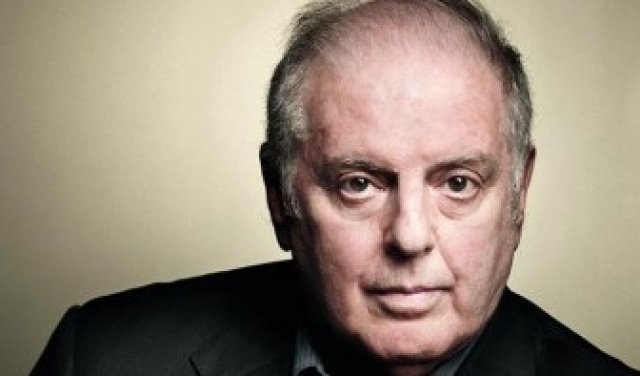

Conducted by Daniel Barenboim

Soloists Wolfram Brandt, Violin

Yulia Deynea, Viola

Carnegie Hall

January 27, 2017

Bruckner's Seventh Symphony brought him acclaim. To get away from the barbs of a merciless critic, he persuaded conductor Arthur Nikisch to open in Leipsig, far from the offending pen. The premier was greeted with fifteen minutes of applause. The Seventh is often called Bruckner's most accessible work. Barenboim conducting shows its subtleties and complexities.

Barenboim has anchored his presentation of Bruckner's symphonies in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose birthday was celebrated with his Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola. The beautiful violin performance by Wolfram Brandt was matched by Yuia Deynea on the darker-toned viola. Setting the musical evening with a supreme melodist who is fond of key play prepares us for the Bruckner which will follow.

Bruckner may have found his God early, but in his music, he searched and searched. This journey makes his compositions compelling. In the Seventh Symphony, the composer is on a constant search for key. Daniel Barenboim allows his orchestra to take the journey under his guidance, but also with a sense of personal urgency in solos and sections. Very early on we hear portions of the 22 bar main theme, a very long one by any standards, on the clarinet and flute. The theme is already inverted, a favorite technique of Bruckner's. Soft trombones calm.

The muffled drum rolls on timpani have a myriad of qualities, sometimes so distant that they can be barely heard, at others, the felt at the end of the mallets move so rapidly tha you imagine two rabbits mating.

Double basses pluck and strum with often desperate urgency. The grand tuba and the smaller Wagner tubas express a textural role but also honor the man Bruckner called ‘the master.' The composer had seen Wagner a few weeks before the master‘s death and the Coda to the gorgeous Adagio movement was a memorial to him. The Wagner tubas, so called because Wagner used them, were on prominent display. Although this was conceived as funeral music, Barenboim draws out its majesty, an appropriate tribute to the master.

At times Bruckner shows the composer toying with rhythm. Two plus three are questioning rhythms and make the music deliciously disconcerting. So too are the struggles to leave a minor key and fail and to provide unexpected keys in one section where the melody has lodged. Since the time of Bach, major has not necessarily been brighter than minor, and the obverse is also made clear in Bruckner.

Barenboim well understands the intricacies of Bruckner’s mind and the composer's musical style. Notes that should belong to one key and yet feel like another are let alone. There is no anxiety waiting for a conclusion. Barenboim can be urgent, joyful and playful, but the pace always feels leisurely. It is as though we the audience is being given an opportunity to hear and feel our own way through Bruckner. It is not always easy, but with the Berlin Staatskapelle as guide, it is a journey full of pleasureful agony and rapt satisfaction at Carnegie Hall.