Pina a BIFF Benefit at Beacon Cinema

Stunning 3D Film by Wim Wenders

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 03, 2012

Pina: Dance, Dance, Otherwise We Are Lost

Directed by: Wim Wenders

Choreography: Pina Bausch

Producer: Gian-Piero Ringel

Stereography: Alain Derobe

3D Supervisor: François Garnier

Artistic Consultants: Peter Pabst, Dominique Mercy, Robert Sturm

Co-producer: Claudie Ossard, Chris Bolzli

3D Producer: Erwin M. Schmidt

Executive Producer: Jeremy Thomas

Editing: Wolfgang Bergmann, Dieter Schneider, Gabriele Heuser

Produced by: Neue Road Movies (Berlin)

Co-produced by: Eurowide (Paris)

In collaboration with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, ZDF,

ZDF theaterkanal und ARTE

In one of the most remarkable confluences of our time the foremost German film director, Wim Wenders, used the still nascent technology of 3D to create a sublime film Pina: Dance, Dance, Otherwise We Are Lost a tribute to the legacy of the innovative German dancer and choreographer Phillipina “Pina” Bausch (1940-2009).

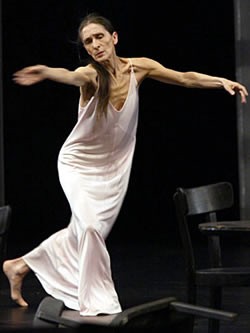

Wenders is know for narrative films, as well as quirky documentaries. The visually stunning and totally absorbing Pina reaches far beyond our received notions of a documentary film. Bausch, who died five days after being diagnosed with cancer, and shortly before filming commenced, is seen only as a slender sliver. There is a brief, vintage, black and white segment of a solo dance and the barest of utterance.

In a “documentary,” particularly of a deceased individual, it is the norm to have talking heads, generally experts in the field, providing segments of information. Here that is confined to short head shots of dancers speaking a number of languages with subtitles seemingly floating in space.

Bausch was noted for her reticence. We learn, particularly from the younger dancers, that they struggled with their craft and yearned for guidance. She worked intimately with individual dancers to build her choreography but never “explained” her concepts. They clung to her sparing comments such as “Surprise me” or “Be more crazy.”

Indeed.

Taking his approach from Bausch in this cutting edge film, which redefines how to treat contemporary dance, Wenders has nothing to say. Actually by the end of the almost two hour film we learn little or nothing about Bausch but have been completely immersed in her riveting, galvanic, emotionally draining work. Wenders has reduced his signature style to a loving eye that allows us to see and feel the dance in a remarkably different manner. This is the greatest and rarest of collaborations between two extraordinary artists, a filmmaker and choreographer.

Audiences have come to expect the Live in HD productions that transform opera and theatre productions to the silver screen. Wenders, however, has gone beyond filming a proscenium production. With his ingenious approach he has created a cinematic art form that is more than a documentation of staged dance. This entails moving some of the dance from theatres to natural and urban environments. Resultantly we experience an extended aspect of contemporary dance that goes beyond what we see in a theatre.

Last night, in the dead of winter, during the “off season” there was a benefit screening at the Beacon Cinema in Pittsfield for the Berkshire International Film Festival (BIFF). Demand for tickets was such that artistic director, Kelley Vickery, presented it on two screens. A feature of the event was a post screening commentary and discussion with Ella Baff, the artistic director of the renowned Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. As Baff informed us, although she was frequently invited, Bausch only appeared at Pillow once, in a duet, in the 1960s.

With the generous support of the German government Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch was known for very large, complex and expensive productions. In the United States her most frequent venue was The Brooklyn Academy of Music.

When contemporary choreographers pass on, such as Bausch and Merce Cunningham, the companies disband. We were fortunate to see Cunningham’s company at Pillow during the weekend when he died. The company subsequently toured for two years with final performances in New York. The Alvin Ailey Company continued under new leadership, now going through a second generation since his death. In the case of Bausch her work is sustained through this superb film.

The film combined excerpts of epic productions such as her interpretation of Stravinsky’s masterpiece for dance Le Sacre du Printemps and complete or edited short pieces including a number of solo pieces and duets.

In all of the work it appeared that the dancers, individually as well as ensembles, were the source for the choreography. She is described as having remarkable ability to see into individuals and to extract their unique passions and special abilities. It was an inside out process and the dance was as effective as, or limited to, the emotional depth, training and execution of that individual.

The dancers she worked with, in some instances for decades, were far more varied in age, body type, and ethnicity than is the norm. Other than Le Sacre du Printemps there was little reference to classical ballet with its consistency of body type and discipline.

Unique movements, dramatic narratives, and surprise were signifiers of her style. She freely conflated many elements and traditions of dance including mime, vaudeville and deconstructions of the chorus line. Underscoring the seemingly limitless invention of the dance was a great diversity of music. I was surprised to recognize the jazz masterpiece “West End Blues” which Louis Armstrong recorded with his Hot Five in 1928. Bausch used it for a titubating line dance with complex arm, hand and finger movements for the full company. It started the film and was then reprieved in one segment as a shot from a distance along a quarry edge.

Often her dances were inspired by the inventive use of props and elements of nature. In one of her signature pieces Café Muller (with music by Henry Purcell) the dance is set in a large room with a clutter of chairs. As the dancers advance one of them clears a path by sharply knocking over and thrusting aside individual chairs. In another work set for stage there is a large boulder and a cascade of water. As the dance developed the water was scooped up in buckets and hurled about. In 3D it appeared that it drenched the audience.

One of the paradigms of physical comedy is to do something, then a variation, followed by more and more variations. One such sequence entailed an embracing couple. A man emerges and rearranges them aggressively. He lifts the woman into the arms of the other man. She is then dropped to the floor. The sequence was repeated ever more rapidly as the audience roared in laughter.

Frankly, I found the audience reaction distracting. I did not experience it as comedy but rather as theatre of the absurd. I identify that aspect of Bausch’s work as related to the expressionist angst of Bertolt Brecht, the French post surrealism of Jean Genet, and the existential deadpan of Samuel Beckett.

Yes, they can make us laugh, and Bausch channels the vaudeville of Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot, or the Lucky speech, but it is always a guilty pleasure. I never quite know if laughter is the correct response to absurd conundrums. Hearing all that cackling just seemed so bourgeois. I just wanted to retreat into self and hunker down with an awesomely daunting aesthetic experience. The film got into my guts and bones.

Then again, critics aren’t quite like other people.