The Monuments Men

WWII Saga That Saved Western Cultural Icons

By: George Abbott White - Feb 07, 2014

Forget what you might have read or heard. The Monuments Men is a wonderful film worth seeing.

Recently I completed reading Pulitzer Prize winner Rick Atkinson's World War II trilogy. His last volume is The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945.

It's 450,000 well researched and written words, and while Robert Edsel's book Monuments Men shows up in Atkinson’s Selected Sources, if my memory holds I'd be surprised if there are fifty of those words about the Allied (chiefly American) attempt to identify, protect, restore, recover and return the millions of pieces of sculpture, painting, drawings and structures that collectively define our diverse human identity over the past two thousand years.

In short, this was the humanist culture the Allied Supreme Commander Dwight David Eisenhower said in a 1943 directive to troops that the Allies were fighting to defend.

From 1942 to 1945—more or less—while bombs were falling and bullets were flying, the Monuments Men protected da Vinci's Last Supper in Milan and recovered Michelangelo's David for Florence. Dozens of paintings by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Klee, Picasso, Matisse and hundreds of others on any Top One Hundred Artists list were located in the depths of one or another salt or copper mine, returned home not only to France and Belgium but to Italy and Germany as well. The magnificent Veit Stoss Altar went back to St. Mary’s Basilica in Kracow, Michelangelo's Madonna and Child to Bruge, and Catholicism's Ghent Altarpiece to, well, Ghent.

Edsel's three recent accounts of this utterly remarkable—and overlooked—MFFA effort sit on the shoulders of six decades and several dozen serious works of scholarship, not least Lynn H Nicholas' The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War.

Mr. Edsel has created a foundation to bring the heroic efforts of a few hundred men and women (really a few dozen until 1945) to general public notice, in part to prevent—or at least limit—future cultural despoliations of the kind that took place during the first weeks of the Iraq War and are happening daily in Syria.

Yet, alongside “overlooked” should be added "uninformed" and "unempathetic," and, because of those, "undervalued"—not least by those who should know better, meaning film critics of the new George Clooney film headlining Clooney, Matt Damon, Cate Blanchett, and a taxi squad of other skillful actors who portray a military anomaly of curators, art historians, artists and art conservators.

Although WWII generals like Britain's Bernard Montgomery liked to say, afterwards, that everything went "according to plan," the men and women on the ground knew otherwise. Hence, there is now more realistic accounts and films that mirror what actual soldiers appreciated as the "fog of war."

Odd then, that a film like Monuments Men which dramatizes that "fog" as it relates to a radically understaffed and institutionally marginalized program of the highest importance to our cultural heritage and future legacy, should not receive a measure of critical respect at least for the historic context recreated.

This includes the very well art directed wartime clothing, food, argot, songs and smokes. (SPAM anyone? and does anyone remember LSMFT means, Lucky Strikes Means Fine Tobacco?).

WW II, in the European "theatre" at least, was fought from Brest to the Ural Mountains, the Firth of Forth to Sicily. Moving across vast distances were millions of men and women, tens of millions of vehicles, boats, horses, airplanes and, thinking of Sochi, troops on skis.

How to reconcile surviving combat against those immense physical realities with what seemed then - and often appears so now - merely abstract concerns about "art"?

European museum directors and curators having suffered World War I's ravages first hand and aware of the devastating effects two decades of increased "firepower" would mean, actually began their damage control planning before September 1, 1939.

Across the pond their American counterparts made their case before elites in the American government before Pearl Harbor, and President Franklin Roosevelt approved the MFAA ( Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives), "program" that would become operational by 1943.

Because Clooney intended this film to be both "entertaining" and "didactic," a necessary license is taken in Monuments Men with the players, American, English, French, German and Russian, and with various key incidents and locales. FDR smokes cigarettes with an ivory holder but while Lincoln Kirstein certainly would have savored his "CARE" package of fine cheese during the Battle of the Bulge, the legendary Boston-born NYC impressario was about twice the size of Bob Balaban who adroitly "plays" him. Characters and incidents are altered, even at times combined, but not the essential WW II details, the "everydayness."

Clooney also exploits the story's several potentials. Chasing after Europe's cultural patrimony, millions of paintings, drawings, pieces of sculpture—the priceless art Nazis have stolen in the midst of fierce WW II combat—is at once a mystery, a treasure hunt, a thriller and actually several surprising miracles.

What’s been taken? Where is it hidden? Will we save it in time from the elements, war, greed, and Hitler’s so- called “Nero decree”—destroy everything if he dies?

By the time the Monuments Men land on Omaha Beach July 1944 in the film, we're more than a month into the Allies' Normandy Invasion, but, as Edsel said at Harvard's JFK School forum recently, "If it looked like the Bad Guys had lost, it was by no means clear the Good Guys were winning."

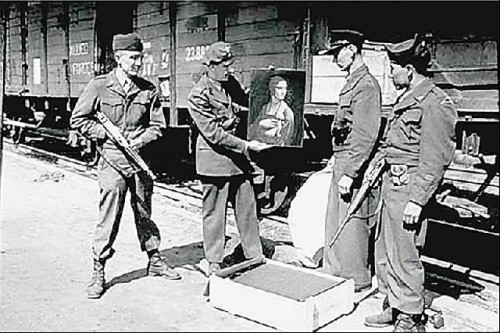

In only one of many deft foreshadowings, the debris of D-Day is everywhere and the beach is still, very still. We sense it will be a long, hard—and often tragic—road to discovery in Goring's box cars and deep below in Austrian and German salt mines.

Clooney as resolute and plain spoken Lt. Frank Stokes, resembling a highly respected but little known Fogg Art Museum conservator (George Stout), is tasked with assembling an artistic Band of Brothers who will protect and recover stuff from Bayeux to Berchtesgaden.

They can’t be young or very in shape; experience is vital, and during an imagined dialogue with FDR, the President tells Stokes, " All the young artists have already volunteered or been drafted."

The art world is a village, so to this restorer not destroyer's recruitment has both the playful yet serious qualities of a pick-up basketball game with friends.

Clooney persuades an up-and-coming Met curator he knows Lt. James Granger (Matt Damon) to be his Paris connection, and then taps a Chicago skyscraper architect, Sgt. Richard Campbell (Bill Murray) and a rotund monumental sculptor, Sgt. Walter Garfield (John Goodman). A knowing but deeply flawed British art historian, Major Donald Jeffries (Hugh Bonneville of Downton Abbey) and a patriotic French graphic design professor, Lt. Jean Claude Clermont (Jean Dujardin) are joined by a New York City Ballet producer/art historian , Pvt. Preston Savitz (Bob Balaban, mentioned earlier) and, almost by chance, a real Pfc, Sam Epstein, driver and jack-of-all trades from Newark who happens to be a recent German-Jewish refugee fluent in German from Karlsruhe (Dimitri Leonidas).

A quarter of the film will pass before we meet Monuments Men’s Paris-based heroine, Claire Simone (Cate Blanchett), seemingly dowdy but an inwardly fiery moral and intellectual figure who risks death daily as a Resistance member tracking looted art from within the Jeu de Paume, the Nazis’ museum storage site.

Simone, quite wisely, trusts no one, least Granger initially, and though her tone softens her gestures, tart observations, wonderfully managed body and facial gestures remind us she is no one’s fool. If she is the film’s “love object,” Blanchett may become fond of Damon but loves only France, and France’s art.

Clooney’s “cool” as the band’s leader means constantly biding his time, constantly forced to act on inadequate knowledge. He is equal parts smouldering and patriotic. He is more than tritely plain spoken. Times are, as he says to a colleague after another's death, "tough," and the simple eloquence of those desperate days is not easily imagined nor, as mentioned earlier, appreciated today.

How Monuments Men works is part of the pleasure of viewing and learning something important that we never knew along the way—although accomplishing the task of making the film happen (as well as acting in it) must have been, for Clooney, a little like putting the Queen Mary into half a walnut shell.

Begin with the fact there are 5 million objects in play, 1400 Nazi sites in which to store them, 300+ Monument Men (and women) at restoration and repatriation work until 1952, and hundreds of Nazi war criminals, large and small (also associated with this unimaginable looting) to be apprehended, interrogated, tried, incarcerated, shot or hung.

Monuments Men moves this big story in slightly less than two hours by focusing on the ways in which the seven very accomplished and attractive characters in the team attempt to learn the location of the stolen art, getting to know one another as they apply and blend their particular knowledge and skills in and forward of the shifting front lines.

Although Monuments Men’s opening has a dramatic clip of Milan’s citizens dealing with the rubble surrounding deVinci’s Last Supper in the frenzied aftermath of an Allied bombing, neither preservation nor the work of another Monuments Men group in Italy is—or reasonably can be—developed.

Like half a dozen other powerful, moving set pieces, they go off like landmines in our unconscious as we reconsider the film’s various meanings.

If the team and their suspenseful accomplishment of the endpoint retrieval task is one narrative, the cumulative visual and emotional effect of two other collective elements are others. The first involves three objects, two major and one minor.

The Ghent Altarpiece has “disappeared.” Also called the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb of God, it is composed of 12 wooden panels, principally “executed and completed” by Jan van Eyck between 1430-1432. Representing a dramatic transition from Medieval to a new “unidealized human representation,” the many and varied figures are absolutely stunning in their realistic art. As Clooney shows slides of it to FDR, he tells the President the masterpiece is central to Catholicism’s understanding of itself.

Often the Monuments Men are seen working in pairs, many times however they crisscross the battle zones of Northern Europe alone. Dividing up half way into the film, Hugh Bonneville cycles in the damp darkness into Bruges to secure Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child. The only sculpture of the artist to leave Italy in his lifetime, the positioning of the Virgin and her Child are different, significantly so, from other representations and similarities have been drawn to the Pieta.

In the course of helping the Church of Our Lady’s priests protect the piece, the marble surface seems to come alive to this errant son; by candlelight Bonneville then composes a poignant note to his Father as a kind of confession and asking for forgiveness.

Young Dimitri Leonidas, aka, Sam Epstein (Harry Ettinger in real life) quickly evolves from driver to colleague. It’s Leonidas who tells Clooney that before leaving Karlsruhe immediately after his Bar Mitzvah in 1938, he nevertheless knew of the Rembrandt Self-Portrait (1650). Like other German Jews however, he was not allowed to view it.

Within the mine, Damon directs Leonidas to a picture which proves to be the Rembrandt. "Say Hello to your neighbor," Damon tells him. Satisfaction, yet like many moments in the film, is fleeting and often bitterly ironic. Alerting the team to a storeroom that proves to be nothing less than the gold reserves of the Nazi state, Leonidas is also shown a barrel of gold pieces. Puzzling. Then Damon’s character identifies the pieces to Leonidas as fillings “from teeth.”

Five distinct sites have a cumulative power in the film, funneling our thoughts and intensifying our feelings. Like numerous luminous visuals (e.g., the biplane’s flight over Paris; several “stolen” views of Vermeer’s Astronomer; Bill Murray, painfully looking his age in the Ardennes officers’ shower, “frozen” in time listening to his daughter’s haunting 45 recording of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” jump cut with an anonymous soldier silently dying from a chest wound; and Cate Blanchett’s face upon being told of her brother Peter’s murder by the Paris SS) their weight is considerable while at the same time light as chiffon.

Paris, the Siegen Salt Mine in Westphalia, the Merkers Potassium Mine, Neuschwanstein Castle near Swangau, and the Alt Aussee Salt Mine in Austria are hefty, appropriately brutal counterweights to the stolen art they conceal. Luring the viewer in, doubts accumulate whether you—or the art—can or will ever get out.

Certainly the case in several circumstances, where faulty or no ventilation, aging bracing and taxed elevators heighten the dangers of mines and other booby-traps, timed demolition by disgruntled Wehrmacht or fanatical SS.

Art imitates life late in the film where Damon finds himself standing on a fairly large landmine, requiring some delicate instant “engineering” by his architect colleagues.

Increasingly shadowed by deception, dissembling, bureaucratic misinformation and the kind of careless—and lethal—dangers attending the end of things, the balance beam of optimism/pessimism tips back and forth until The Monuments Men’s very end.

Not unlike the Allied soldiers killed and maimed up to and even beyond VE Day May 1945. A jarring—but ideologically accurate, in a way—note bookends the film. As the Monuments Men close in on, among thousands of others, the Ghent Altarpiece and Madonna and Child in the Alt Aussee, banging shut the crates echoing the film’s opening, Russian troops race to the same Austrian spot to close shut the “spheres of influence” deal Churchill and Stalin sketched in Moscow.

There is the apt dramatization of the Monuments Men "program" ("They mean us to fail,"), limitations of personnel (few), communication (scrounged and fitful), and mobility (haphazard and unassigned) all the while peppered by, well, bombs and bullets — directed at men in their fourth and fifth and even sixth decades who have been involved in discerning authorship, curating exhibitions, lifting nothing heavier than pencils or picture frames for their previous adult lives.

This film is fictionalized history at its best. The Monuments Men celebrates the triumph of a few untypical, even quite unique, brave soldiers who literally saved our Western Cultural heritage.