One Evening:Two Works at Komische Oper, Berlin

J. Weinberger and G. Verdi

By: Angelika Jansen - Feb 15, 2020

Die Komische Oper, Berlin, presents:

Fruehlingsstuerme (Spring Storms) by J. Weinberger and La Traviata by G. Verdi

It is always a time for heightened expectations when one goes to any performance at the Komische Oper, Berlin. It will not necessarily be enjoyable for everybody but it will definitely always be provocative. This was proven to me again when attending two vastly different shows, a new production of the long forgotten operetta Fruehlingsstuerme (Spring Storms) by Jaromir Weinberger and the globally beloved opera La Traviata by Guiseppe Verdi.

Fruehlingsstuerme is the code word for a fictitious Russian military offensive led by General Katschalow (Stefan Kurt) in the Russian Japanese war of 1904 in Manschuria. Turbulence and intrigue abound as the beautiful Lydia Pawlowska (Vera-Lotte Boecker) discovers a Chinese servant to be Ito, A Japanese General (Tansel Akzeybek), spying on the Russians. Lydia loves Ito and wants to free him when he is apprehended. To do so she needs to seduce the general Katschalow to find the code word. She decides to hold a big festivity where she is sure to reach her goal. However, the love-struck Katschalow keeps enough of his senses and gives Lydia a false password – and all goes wrong. Sometimes later, during peace negotiations, the messy situations conclude in happy endings or reasonable settlements for all involved parties.

Barry Kosky, head of the Komische Oper, has directed and resurrected the operetta that originally opened in January1933. It is the last work by the Jewish composer Weinberger that was produced in Germany. He had become famous with his opera Schwanda in 1927. When Fruehlingsstuerme opened, even though Germany's famous opera singer, Richard Tauber, drew crowds, the Nazis forbade the operetta after a short two month run because of its Jewish composer. Weinberger fled the country soon after.

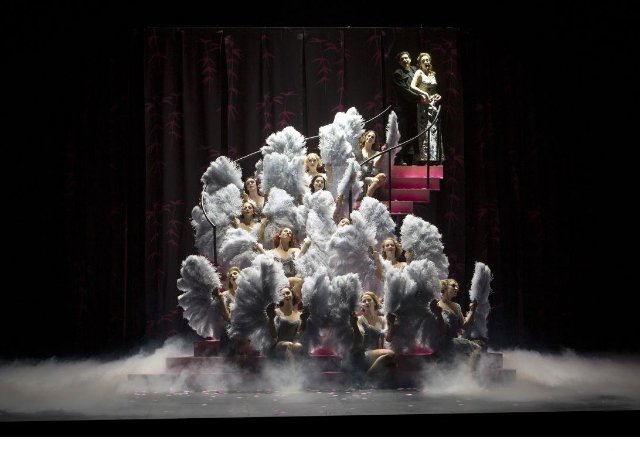

Kosky resurrected the operetta and produced it under the musical direction of Jordan de Souza. The stage settings and lighting by Klaus Gruenberg were stark but very effective. He used a box construction that opened or closed and rotated as the scenes switched. The choreography by Otto Pichler provided many comical turns, dangerously close to slapstick. It really spruced up the somewhat dated score, and made the evening into an enjoyable tour the force. Especially the big dance number, close to intermission, surprised with its over-indulgence. The dancers played with huge feather fans and used the setting of a glamorous descending staircase, as in a vaudeville show with red rose petals falling from above. It was quite a scene and quite over-the-top.

Not at all in danger of being suspected as tongue-in-cheek was the performance of Verdi's most famous opera La Traviata. Jordan de Sousa, again as musical director, helped Nicola Raab succeed in having the singers shine. Surprisingly old-fashioned it seemed as the wonderful arias were brought to prominence on stage. It really turned into a setting of arias within the opera.

Only at the Komische Oper could it happen to integrate a 19th Century concept of staging arias first and then arrange the action around the singers and be rejuvenated. Vera-Lotte Boecker succeeded in both. She sang her Violetta Valry with a delicate soprano and she also convinced as the dying courtesan. Her lover, Alfredo Germont, sung by Marco Ciaponi was appropriate. The wonderfully strong baritone, Guenter Papendell, as Alfredo's father, Giorgio Germont, who brutally forced Violetta to leave his son dominated the second act. Yes, the singers did shine, but the overall stage settings by Madeleine Boyd felt disjointed, as they seemed torn between a contemporary and a conservative approach. Period costumes were interchanged with modern outfits. Cell phones and computer screens were constantly attended to by people in 19th Century outfits, film sequences with Greta Garbo as Violetta ran as a back-drop on a torn curtain. A naked couple that copulated on a long table must have been added as being symbolistic for a decadent society, otherwise there was no other need for such a gesture. The stage itself represented a factory with an industrial window covering the back that stopped onlookers from entering the space.

Both works had their pros and cons. But, whatever the Komische Oper shows, it is worth an attendance since surprises and interesting interpretations are definitely in-store. Besides, foreigners are not at a loss. Simultaneous translations can be followed. Thus, anybody who is curious about new ways in looking at operas and operettas should not miss a visit to the Komische Oper in Berlin.