WBCN and the American Revolution

Bill Lichtenstein Discusses His Documentary Film

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 03, 2019

In 2006 Bill Lichtenstein was interviewed by the Boston Herald. He discussed a film project and asked for readers to contact him if they had tapes of broadcasts, photos and other documents. That resulted in what he describes as the first open sourced film.

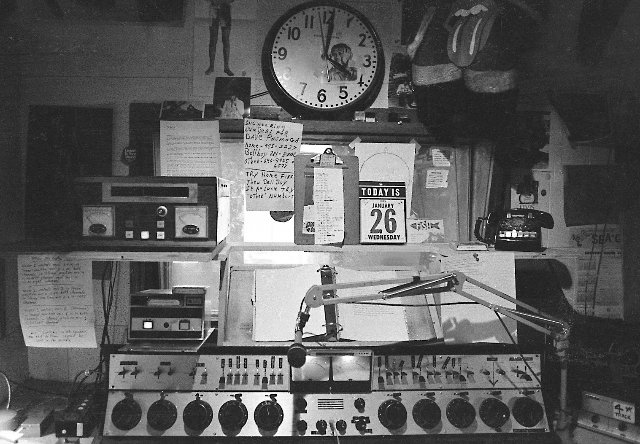

It is usual to start with material to create a documentary film. In this instance there was no archive related to WBCN. Now there is an extensive one. The idea existed before the material to illustrate it.

We wish to thank Lichtenstein for making available stills that accompany this article. Additional images were provided through the archive of the University of Massachusetts. In particular we are grateful to the estates of Jeff Albertson and Peter Simon for their vintage photographs.

Charles Giuliano What’s happening with the launch of the film, WBCN and the American Revolution, in the next few weeks?

Bill Lichtenstein There’s a sneak preview screening of the film at the DC Film Festival on March 7. It will be followed with a panel and questions with Sam Kopper and perhaps someone from NPR. On March 9 the film plays at the Cinequest Film Festival in San Jose. It will play again on the 12th and 13th. There are plans for a Boston launch in April.

CG You said that the film was wrapped last night. What did that entail?

BL You could compare it to Photoshop but the film was done with an editing program. There are limited desktop capabilities regarding imagery and sound. You then take a film into a studio for color correction to make it look great and for sound mix. On a desktop system you can fade things in or out and do a certain amount of noise reduction with old broadcasts. In a full recording studio you can really work with the sound.

We spent about three weeks then outputting it which was last night. You have to watch it, see that it’s OK, then send it out.

CG Start to finish how long has this film taken?

BL Fifty years. I started collecting stuff when I was there. (Starting in 1970 when he was fourteen.) When we started the project there were no WBCN archives. A substantial amount of material we started with was what I had collected while at the station. At that point it was my own collecting of stuff.

In the 1980s I was working with another producer about doing a documentary on Phil Ochs. The project dragged on for years. We were working with his sister. His brother was Michael Ochs the famous archivist. He was working with another producer and the family decided that they would go with that project. It came to an end for us but the idea of it was on my mind.

In the midst of the Iraq War, Post 9/11, George Bush and a lot of National Security issues what emerged was why more artists, musicians and people weren’t speaking up. What was going on?

Bruce Springsteen did a benefit for John Kerry and was accused of being too political. In our day if you did a benefit for a democrat for president you would be accused of selling out.

So there was an idea to tell that story which Phil Ochs personified. In the 2000s another thing was an explosion of archival material coming on line. With Napster all these songs I had forgotten about were suddenly available again.

(Shawn and John Fanning, along with Sean Parker, launched Napster in 1999 as a peer-to-peer file sharing network. The software application was easy to use with a free account. The service provided easy access for millions of internet users to a large amount of free audio files. Approximately 80 million users were registered on its network. It was shut down in 2001.)

Archival material seemingly lost to the ages suddenly reappeared. One was a photo of Danny Schechter (WBCN news director) the day Daniel Ellsberg turned himself in. The photo appeared on line of Schechter standing there with a microphone. There was a tape of Bruce Springsteen’s first interview which I heard at the time.

Something happened and the tape disappeared from WBCN. It was in the Maxanne's (Sartori) stash in the production room and it was stolen. The tape we used at the station was ten inch reels and they run out after 30 minutes. It recorded the interview but at the end a recording of “Blinded by the Light” the tape ran out.

Suddenly it’s on line but stops after a minute and a half which tells me that it was derivative of the actual tape.

Because of those two things I began to think that you could do a film about how media could create social change using archival material that was out there. At the time there was no archive of WBCN or the counterculture of Boston. The material was scattered.

(The David Bieber archive, now some 600,000 items, was then in storage and not accessible. That material has been transferred to an industrial space in Norwood where it is being unpacked and catalogued.)

In 2006 The Herald did a piece in which they discussed my plan to do a documentary film on WBCN. In the article it stated that if anyone had related material to send it to me. That’s what kicked it off.

We collected archival material for a few years as that’s what we needed to drive the story. For most documentaries you tell a story and then use images to put up on the screen. This was the opposite. We had to find what material was there and then how to tell the story.

It was like archaeology. If we found the toe of the dinosaur then maybe bones from the foot are here. We would find something like a tape of Patti Smith at Paul’s Mall. Then we would try to find if there were any photos. We began to cluster sound and pictures around particular events.

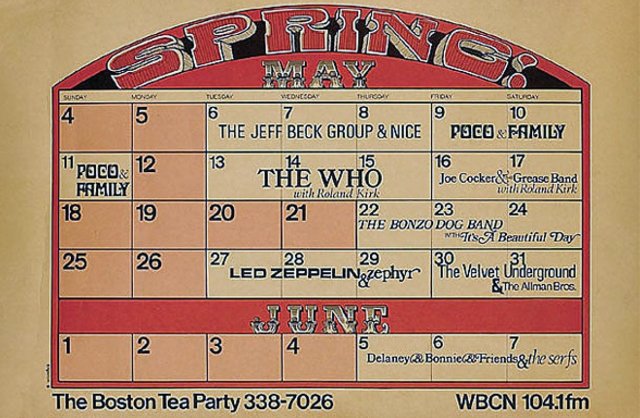

What ended up in the film was what we had the best archival material for. From the Tea Party we used The Velvet Underground and Led Zeppelin because we had the material for them.

In 2010 we started doing interviews and raised money in 2012. We continued to raise money and shoot through 2016. So 2006 to 2010 was pre-production. When we got money shooting was four years from 2012 to 2016. We started editing in 2017. This past year and a half has just flown.

CG It ended last night.

BL At the end of last year we had a rough cut and something we could show. It was in pretty good shape a couple of months ago. We showed it to some people and everyone liked it. We’ve been finishing up since.

CG What’s the potential audience?

BL There’s two clear target audiences. There are people who remember the era. WBCN is set against the story of how we went from peace, love and LSD in San Francisco in 1967, hippies on Boston Common in ’67, where the message was peace and love will save everything. How did we get from there to Nixon’s resignation (August 9, 1974), and everything in between? There was Vietnam, Watergate, Kent State, and the whole story of the 1960s that this is set against. The film touches on the important cultural aspects that impacted WBCN.

CG It is ironic that right now we are taking about Nixon on a day when Michael Cohen, Trump’s former private attorney and fixer like John Dean decades ago, is testifying before Congress.

BL The film has gotten a strong positive response from young people. They are struggling with how you use media to create a social, political and cultural change. They are struck by how much was accomplished during that period.

We focus on the fact, for example, that there were no women on the air at WBCN. There was a protest about it which resulted in Maxanne (Sartori) coming to town. We have a tape of Jerry Williams of WBZ saying on air in 1970 that women don’t belong on the radio. He said that they don’t have the voice for it and try to sound authoritative. It’s just not appropriate. A woman called in and said “If I have the radio on I want to listen to a man’s voice. If I want to hear a woman rattle on and on I can call one of my girlfriends.”

As a result of the protest women were given Bread and Roses a weekly, one hour slot. As part of it they read from a 1970s, New York Times obituary which is in the film. It’s about a 17-year-old Barnard student who died of a heroin overdose. The obituary quotes her high school principal as saying essentially, she was young, talented and, if she were a boy, you would say she had a bright future ahead of her.

Young people are surprised at how bad it was not that long ago and what it took to change it. WBCN taking the lead and putting women on the air helped to change things. They also love the bands of that era. It’s a universal story.

CG Let’s talk about the 1960s. A thousand days into Camelot President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. The Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964 pulling America out of months of mourning. Their final tour ended in 1966. In 1967 there was the Summer of Love. WBCN went on the air in 1968. That summer Dave Wilson, Sandi Mandeville and I published Avatar. In Chicago there were riots during the Democratic National Convention. When people talk about the 1960s they really mean starting late and continuing into the 1970s. The counterculture fell off the cliff by the 1980s.

BL In this film the 1960s began with the Summer of Love. At least the story begins then. Its manifestation in Boston was hippies on Boston Common and their clash with Boston’s aristocracy and police.

Right after Kevin White was elected (as Mayor) there were hippies camping on Boston Common. In the wake of Summer of Love they were coming in large numbers by the summer of 1968. There were people on Beacon Hill saying get these kids off Boston Common. They were arresting kids and beating them. It’s in the film and for me that’s where it starts. Ray (Riepen) opened the Tea Party and it went from there.

At the end of the film Charles Laquidara says “I think the 1960s ended when radio became not underground but commercial.” Nixon resigned so that’s how it’s framed. Nixon is the protagonist that this whole thing is set against.

The film presents the role that WBCN played in opposing Nixon by supporting the Moratorium on the Common and the anti FBI efforts that were going on in that period. Boston was a hot bed of opposition and WBCN was a major part of that.

The story has not been told of the role that Boston had in taking it from peace, love and LSD to a politicized anti-war mode. WBCN was very clear in helping to create social change.

CG In what sense was Boston different from San Francisco?

BL The heyday of San Francisco was the launch of the counterculture in 1967 with Summer of Love and all those great bands. There was a free speech movement out there but I think the argument can be made that the epicenter of the counterculture, in 1968, shifted from San Francisco to Boston. Cultural manifestations continued in New York but they became commercial in fashion, style and the mainstream of America.

Fringe stuff became part of the mainstream. New York, in commercializing them was not as dangerous, threatening and radical. San Francisco passed the torch to Boston. The argument of the film is that it developed in Boston. I don’t want to say that it was more, less, or better than in San Francisco. But it’s surely the story that’s not been told. When you see the end of our film you say, wow, I didn’t know all that stuff. There was a whole body of things that went on here that was important to the 1960s.

The great untold story is the reticence of Boston/ New England to celebrate its own history.

When Ray Riepen came to Cambridge to attend Harvard Law School (a graduate program), because of him, there was The Boston Tea Party, WBCN, and The Phoenix. He had a vision of creating a newspaper like the Village Voice.

If you play a It’s a Wonderful Life game, had he not been born, had he not come to Boston, had he not been accepted at Harvard Law School, what would have been different in the world? Imagine the difference in the 1960s had there never been a Boston Tea Party, never been a WBCN, and never been a Phoenix. Think of the impact that had down the line on all the bands, and the writers.

In my mind Riepen is the most important person in the culture of the 1960s. People have suggested that Riepen would be like Bill Graham if Bill Graham had owned the Fillmore, a major radio station, and the Village Voice all at the same time. Which he didn’t.

Who was on a par with Riepen; Abbie Hoffman, Bill Graham? Riepen’s impact on the 1960s was enormous. All of us who have gotten into this field owe it to Ray and the film makes that case. Yet Ray doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. Very few people know who he is and I don’t know why.

My theory is that there is a Calvinist, New England we don’t blow our own horn kind of thing. But there hasn’t been anyone here, like Graham did in San Francisco, to compel that. If you go to the East Village there are books and walking tours. Guides point out that’s where Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl. That’s where they sold the first copy of Evergreen Review or where The Velvet Underground performed. Boston has never done that and I don’t know why. There’s such an important history here that’s never been fully told. That was a part of the mission of the film. We have the actual sights and sounds and stories from people who were there. When you see it you can decide where the story falls in terms of historical importance. I have not pinned down why, as you say, that this history has not resulted in exhibitions and books. It should all be common knowledge and just isn’t.

CG How does Ray Riepen emerge?

BL He’s a central character in the film.

CG Curiously at the height of seemingly dominating aspects of the Boston youth market, with a rock club, radio station, and newspaper he sold these interests and left town.

BL It’s not something we can get into so I can’t comment on that. But I can say that the history of business is full of brilliant innovators who started things they didn’t stick with. Rolling something out, sustaining it over time, and bringing it to fruition is another skill. Ray’s greatest skill was dreaming up world changing things. As he told me he was less interested once it was up and running.

We talked a little bit about tensions at WBCN that don’t make it into the film. He said “I got WBCN up and running but by then I was already onto the Phoenix.” He wasn’t focused on WBCN any more. He started the Tea Party and when that was up he was off to WBCN. As soon as that was running he was off to The Phoenix. But, he was owner and operator of each of those. People expected him to be the person in charge.

I know very little of the tension at The Phoenix but I know it was there. So that’s why eventually he left town. If it had been his intention to run an empire he could have hired different people to run things but that would have been a different approach. His primary interest was the entrepreneurial aspect.

He went to LA and tried to replicate WBCN there but it was more difficult because it didn’t have a built in youth audience. It was a much more diverse city. WBCN worked in Boston because of the nature of Boston. LA was a very different scene and the lack of young people meant it didn’t work there.

CG For the time, despite his Midwestern, straight, lawyer persona, curiously Riepen was visionary, and progressive to the point of radical/ Avatareque. He was a dream maker. In the zeitgeist there were many doing all kinds of things. There were startups, publications, art galleries, clubs, bands, and entrepreneurs of which few survived.

If you look at the spectrum of what started in and around 1968 there is an interesting pattern. Leadership morphed from visionaries to hip capitalists. When his contract to run the Tea Party expired Steve Nelson left over a salary dispute. He was replaced by Don Law who ultimately was a businessman. He had none of the flair and community outreach of Bill Graham. The same might be said of publisher Steve Mindich. T. Mitchell Hastings sold WBCN and eventually the station was more focused on making money. Other stations sliced off aspects of its style and charisma.

By the mid 1980s what had been the radical counterculture was all about the bottom line.

BL At WBCN it was the announcers who decided what ads ran and not the advertising and sales staff. We weren’t interested in ratings we just wanted to do good radio. Turning down advertising DJ Jim Parry says in the film “Are you insane?”

Ray says we get a call from some media buyer and they are acting like they are doing us a favor. And we had to tell them, no, the jingle is too ugly for our radio station. There’s a story in the film which shows how radical he was.

He hired Bo Burlingham to be news director. He was in the Weathermen until the New York townhouse blew up. (They were making bombs.) That created the Weather Underground. He stayed above ground and around that time he and his wife Lisa decided that they wanted out. He met Ray and Charles and they hired him as news director.

His second day on the job he was indicted with twelve other Weathermen for a plot to bomb federal buildings around the country. Bo went to tell Riepen.

Ray told him, look, I’m running a federally licensed business. I don’t think I can have someone indicted for blowing up federal buildings on my payroll. But I own a paper called The Phoenix and if you want you can write for them. You could tell that Ray was proud of the fact that, although he couldn’t keep Bo at WBCN, he could get him a job at The Phoenix. Ray was very radical and not a hip capitalist in my mind.

In the film Jim Parry describes him aptly. “Ray was what we needed. He had an understanding of the counterculture but with the mind of an entrepreneur. He had this vision and it was my way or the highway.” He was consistent politically, culturally and socially with what was going on. It wasn’t like he saw a chance to exploit it for money.

CG There is the famous story of Ray calling the station and telling a DJ not to play drum solos. Then Charles Laquidara followed with a show of drum solos. To what extent did Ray interfere with aesthetic decisions?

BL I think not. Ray loved the idea of doing these things. He was not involved in the aesthetic decisions of the station in any way that I knew or saw. I think he was at a party with some people and called in a request.

CG Do you explore the relationships between Riepen and Jessie Benton? They knew each other from Kansas and Jessie wanted help to get divorced in order to marry Mel Lyman.

BL Only in the sense that it led to him taking over a lease that resulted in creating The Boston Tea Party. Jessie called and asked if he could help negotiate a lease on a building. She said she was working with Andy Warhol and Jonas Mekas. They got a Ford Foundation grant to open a Filmmaker’s Coop. Ray met with the owner who said “I have three people looking at the property. If you want it you have to sign the lease right now.”

He wrote a check for $5,000, signed the lease, and called Jessie. She said “Oh, I just heard from the Ford Foundation and there is no money.” Other than declare bankruptcy Ray said “Why not open a rock club.”

CG Steve Nelson tells the story of being hired to manage the club three months after it was founded. By then Riepen had bought out a partner David Hahn who was an MIT graduate and entrepreneur dealing in Army surplus.

There was serendipity as the acts that appeared at the club were also heard on WBCN. Back then kids could hear Led Zeppelin for $2.50. Discuss the transition to when hip capitalists saw the potential and top bands moved from clubs to stadiums. Now tickets for concerts sell for hundreds if not thousands of dollars.

BL By 1974, acts that appeared at the Tea Party were selling out Boston Garden. That’s the third act of the film when WBCN ends up on top of the Prudential Building. An anti- establishment station was struggling to hold onto its values from the top of the Pru.

CG What I am hearing is how the counterculture slid down the slippery slop to the mainstream and commercialism. The cultural landscape of Boston morphed from radical/ visionary to commercial.

BL I’m not sure it goes that far. We tell the story in a factual way that’s respectful of the people at the station while acknowledging what was going on. You can draw your own conclusion. There is a time line. Nixon resigned in 1974. When we moved to the Prudential there were more demands and management started airing national ads. Some felt they couldn’t hold onto their core values because of that. Things that were fringe were rapidly becoming part of the mainstream culture. We leave it to the audience to connect the dots rather than make a statement. It was a combination of things.

If the public maintained its radical commitment it might have been a different story.

As a student in 1973 I did a sociology paper when the Real Paper was sold on the theme of has it sold out? I called Andy Kopkind and asked what happened? He said “A bunch of us got together and decided that having a little comfort wasn’t counter revolutionary.”

CG What was your role at WBCN?

BL I started at fourteen on the Listener Line. I was finishing a shift and Danny Schechter, then in the first months as news director, asked me if I could do him a favor. He gave me a tape recorder and told me to go up the street a couple of blocks to police headquarters. He said “There’s a protest there over the killing of this guy Fred Hampton. Push the red button and just say to people ‘why are you here?’ then listen through it and pick out a cut and bring it to me.” Very soon I was producing stories for him. They were successful enough that Norm Winer (program director) offered me a shift. It was on Saturday night which I did until I was eighteen. Then I went to Brown but would come back during the summer.

Al Perry later told me what happened. There was a staff meeting and Charles Laquidara was going on and on about high school kids. I said “If you want to get them to listen you have to reach out to them.” Al said to Norm “We should give that kid a show.” I went on under the pseudonym of “Little Bill.”

CG If you visit Boston today nothing looks the same. Everything that meant so much to us, rock clubs, WBCN, alternative press no longer exists. Even physically, with so much development, the skyline is different. The counterculture proved to be unsustainable which is a factor in why there has been so little critical attention paid to the era. Out of sight and out of mind.

In the past few years there has been a change. Books like Carter Alan’s Radio Free Boston: The Rise and Fall of WBCNand Ryan Walsh’s Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 and other books have sold well. There is your soon to be released film. The book I am working on now has a bibliography of 32 titles. With aging primary sources there is some urgency to tell this story. There is a motive to record our history as well as provide a legacy for future generations. Can you discuss why there is a growing interest in looking back at Boston?

BL Much was accomplished during that period including driving two sitting presidents out of office (Johnson and Nixon). The departure of Johnson is in the film. We helped to end an unpopular war. During that time there was the first highlighting of the importance of ecology. There was the struggle for equality for African Americans, women, gay and lesbian people. That entailed a dramatic identification of problems and a shift to issues that continue to be significant social problems; including now a criminal president in the White House. These issues have sustained themselves.

For young people today there is a desire to make the world a better place. With social media they have a set of tools we never had. There is an inevitable look back asking several key questions. Using typewriters and corded phones how did so much get done in a relatively short period of time? From the arrival of hippies on Boston Common, to Nixon’s resignation, was just seven years. If you look at pictures of young people participating in the Love Ins they have short hair and are dressed in a tweedy, preppy manner. In 1967 the style hadn’t yet evolved. In a year or two it exploded and in seven years all this stuff happened. Another question is what role did media play in these events?

Borrowing a line for Apple, “Today it’s never been easier to be heard or more difficult to communicate.” With technology of the time WBCN reached some 150,000. A kid walking down the street today can post to You Tube and reach a half billion people instantly.

Protest in those days wasn’t just showing up for a demonstration on Boston Common or calling a Congressman. The whole culture played a role in the change.

I was talking with John Scagliotti about WBCN’s role in the change to gay issues and he said that they had covered them. In 1973 there was the first gay protest in Greenwich Village. In Washington Square Park a number of competing groups were literally about to have fist fights. Bette Midler, who was home listening, literally raced to the park and performed. That changed the whole tone of the rally. John says that, and we have it in the film. WBCN always led with the culture. Covering the first Gay Pride protest we focused on Bette Midler.

People looking for social change the lesson of that era is that it’s not just signing a petition. It was really the whole culture and its music. It’s the artists like the guy who created the famous clenched fist that you see on posters. It was created by Harvey Hacker an architectural grad student at Harvard's Graduate School of Design. It was used in the Harvard Strike. The confluence of all those elements is an important lesson.

For young people watching the film it shows how we did it with object lessons for today. As an intern said to me “Tell me again how you guys got rid of Nixon?” There is a natural tendency to want to look back. What was the influence of Abbie Hoffman, Angela Davis and Herbert Marcuse?

CG They were all at Brandeis during my undergraduate years. I heard Marcuse, Eugene Debs, James Baldwin, Eleanor Roosevelt, Alan Watts, Max Lerner, Irving Howe, Abe Maslow. They all spoke to us. It was a part of our radical education. Abbie was a senior, along with Martin Peretz, when I was a freshman. I knew Angela from having coffee in the snack bar with my friend Evan Stark. You mentioned that Norm Weiner went to Brandeis.

BL After Kent State we have a clip of Walter Cronkite announcing a national student strike but the focus was on Boston. He states that 240 schools are on strike. Brandeis was the national center for organization. The first Moratorium started in Boston.

There were people like Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn. We all know about that inherently. But the story has not adequately been told of their impact on the 1960s. What happened in Boston filtered out nationally. As Danny (Schechter) says in the film “Boston was a battleground.” We didn’t have room in the film but Daniel Ellsberg was in Harvard Square at 3 AM Xeroxing the Pentagon Papers.

CG What kind of obstacles did you have to overcome in order to make this film? Approaching potential donors one might imagine skepticism.

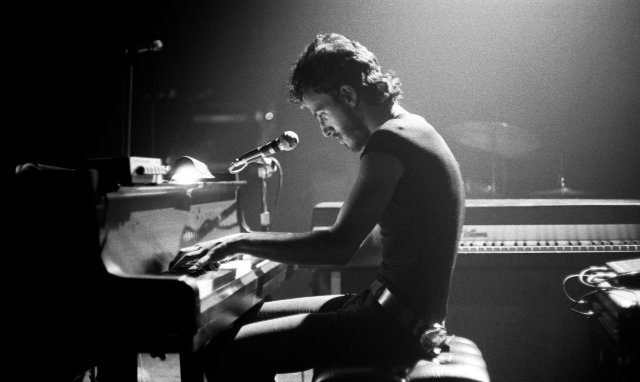

BL I listened to tapes that we started to find like the first Bruce Springsteen radio interview with Maxanne Sartori on WBCN. Or the night that Patti Smith, performing at Paul’s Mall in a remote broadcast, unleashed obscenities on air.

Or the morning when the FBI busted in the door of the commune Danny Schechter was living in to bust Bill Zimmerman. Danny had a tape recorder running. When they asked if he was a resident of the house, and an individual on their list, he responded that he was a reporter covering the bust. That took chutzpah as he may have been in pajamas and a bath robe at the time.

You may have heard this stuff live but not for all these years.

Layered on that I went to Florida and met with Jeff Albertson’s widow who is since deceased. I was looking for photos from that era. She said “Whatever I have you’re welcome to. I haven’t opened this closet for a year since he passed away.” There was a stack of boxes from floor to ceiling. It was all negatives. There were between 50,000 to 70,000 negatives. There were some contact sheets. He started shooting for the BU News, then the Phoenix and Globe. He had a photographic history of the era.

We called around but the cost was prohibitive. It was fifty cents or a dollar a scan times 50,000. We struck a deal (with Robert Cox archivist for the library of) University of Massachusetts, Amherst. They would acquire them, digitize them, and make them available back to us.

http://credo.library.umass.edu/search?q=*&fq=FacetCollectionID:muph057

Peter Simon said “I’m interested in doing the same thing. I have all these prints and negatives and they should be in an archive.” He has since passed away.

http://credo.library.umass.edu/search?q=*&fq=FacetCollectionID:muph009

So we were finding amazing material as well as all of these vintage photographs. Let me give you an example.

Ray Riepen was doing well with the Tea Party. He found out that someone was opening a competing club Crosstown Bus. Long in advance they had booked The Doors. Out of nowhere “Light My Fire” became the number one song in America. They were buying TV commercials which nobody had ever seen. Their goal was to put the Tea Party out of business.

Andy Warhol had just been on the cover of Life Magazine. Ray called him and said “I’ve been playing the Velvet Underground here for weeks. You owe me. I’m asking you. Bring a camera and I don’t even care if there’s film in it. Be up here next weekend I need you.”

Ray printed handbills. I just saw one on line and I swear it was selling for $10,000. It read “Be a Part of What’s Happening. Be in Andy Warhol’s Next Movie.” They handed them out all over town. That night (Friday, August 11, 1967) that the Doors were at Crosstown Bus there was a line of women around the block to get into The Tea Party. Apparently, Crosstown Bus did not even sell out.

Andy was there shooting and shooting. In 2011, when I interviewed Ray, he said that Warhol didn’t have film in the camera. A couple of years later the film was discovered with raw footage of what he shot that night of the Velvet Underground. We licensed the film. Last night when I was watching it, amazingly, it occurred to me that he was editing it in the camera. It looks like psychedelic movie footage you’ve seen a million times. There’s a flash then a quick cut. But he was doing it in the camera as he was shooting.

In the film, a few moments later, Steve Nelson references “Sergeant Pepper” then Peter Simon talks about “A Day in the Life.” There’s a short clip of a Beatles film which they made to go along with the song. It hit me that the style of out of focus, in focus, quick cut, a close shot of someone’s face, all of what we equate with 1960s avant-garde filmmaking began with Andy. This was an example of that from The Tea Party. I would argue that you can’t find anything like it before that.

When I saw the material and Warhol footage I knew that there was a film here. In Boston there was a sense that this will be a film about WBCN. Nationally, there was a feeling of who cares about a radio station in one city. That’s what we had to contend with. As a result we did it completely independently. It was not bought ahead of time by somebody like HBO. So we had to raise all the money independently.

The archives, all of my time and that of others, were not paid for. They were all donated. In the case of archives people made them available. We got help along the way from many, many people. The final cash outlay for the film will be around $350,000. That seems like not a lot for a serious documentary film.

But the value of Peter Simon and Jeff Albertson’s photos alone, if we had to license them, would be well over seven figures. You will appreciate that the film has been done in the WBCN way. You put the word out and hope someone will come along and help. We had a Kickstarter campaign that nearly a thousand people contributed to. People sharing their archives was hugely important.

Most documentary films start because there is material and you are going to make a film about it. Our starting point was let’s make a film about a radio station for which there are no tapes. Maybe we can find them.

When I started in 2006 Charles Laquidra told me “I don’t even know how to share a photo on the internet.” In the Herald story in 2006 we called this “The first open source documentary.” If you look on Wikepedia it says that we were the first. It was a novel way of making a movie.

During those seven years you can list the events. There was the Boston Common Moratorium. Abbie spoke and got everyone riled up. They went and trashed Harvard Square. Another landmark was when The Grateful Dead played BU.

CG I covered that gig for the Boston Herald Traveler. Later I hung out with them in the Green Room of the Tea Party then on Lansdowne Street. There was an easy access to bands that no longer exists.

BL There were a lot of people at key events with cameras. Our hope is to create a critical mass of material from that era, particularly in this region, and to create cross references. If someone reads something you wrote, for example, they might ask if there are photographs to look up? At U. Mass Amherst chances are you can find a photo of that event. Jeff probably has a photo of you in there somewhere. The hope is to contribute to a critical mass of ideas, film, audio, words and images. Everything I have is going to U. Mass Amherst. Cliff Garboden’s papers went to Northeastern but U. Mass has his photos. They also have Ray Mungo’s papers, Liberation News Service, and a world class folk archive with Club 47 and Joan Baez. (She attended BU for six weeks.) The hope is not just to have it in boxes but to put it online.

CG What is the prelaunch buzz for the film?

BL There’s a huge interest in Boston. We ask for comments after previews and someone wrote “Perhaps the first true film about the 1960s.”

CG Having worked on this project since 2006 how has it changed you?

BL When I first talked about it with Charles Laquidara he was skeptical. But he said “There hasn’t been a day that’s gone by without someone saying to me that something that I said or did on the air changed my life.” That to me was the box that opened to make this film. Not just what the station put out but the impact it had. We were a part of the resistance. As station manager Al Perry put it “If we give in to these people we’re finished.”