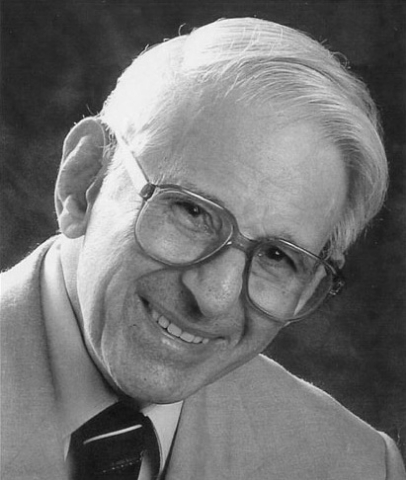

James Cohn All American Composer

Rich Brew of National, Folk, and Classical

By: Djurdjija Vucinic - Mar 17, 2017

Joe Rosen, a crucial patron of the arts in New York City, often introduces the work of a composer who should be better known, James Cohn.

James Cohn is a composer who creates his own discursive network. Late romanticism had a truncated development, yet Cohn shaped this "musical era" in a personal sensibility. He mixes late romanticism and modernism.

Like some of the best-known national composers, he uses beautiful melodic invention. Like Bartok and Dvorak, Cohn has plucked melodies from America’s folk music, adding distinctly modern disharmony, and yet capturing the rhythms, for instance, of the West. Cowboy Srut gets that swagger perfectly. The harmonica suggests "Yellow Rose of Texas" in Campfire. The Prairie Sunset is given a fuller treatment, set as the sun does in the land of the big sky. Circuses are a more universal image, but Cohn's circus marches recall the soon to be defunct Ringling Brothers’ Elephants thundering and delicate trapeze swings as well.

In his Concertos, Cohn is clearly inspired by the treasure trove of folk songs. For instance, his Concerto for trumpet and the Orchestra was inspired by American jazz. He offers rich challenges for the trumpet soloist in melodies we associate with classic jazz.

The soloist as protagonist has a long significant entrance in precise rhythm to bring out a melodic theme created from chord arpeggios. After his statement, Cohn introduces pizzicato strings which immediately soften the flow and change the color of the sound. The music is building the narrative in the opposition to the co-dependent orchestra and soloist. They are compact and unique.

Cohn plays with the orchestra and the soloist in arpeggio sections. The first movement can easily trigger pictures of a generic opera setting. The opening is an overture with pictures and landscapes. The composer is a master of atmospheric expression based on stabile harmonic setting.

A recognizable motif in the trumpet solo is the nucleus of the movement. The protagonist goes through the transformation, he listens and questions. In the second movement the composer switches settings and styles, yet he's always aware of the bond within the "classic" form. This sound texture and the melody are vivid and picturesque. The variations give this piece an airy feeling. You might be glimpsing a view around a corner which reveals itself gradually until the whole image is exposed. The following movement opens with a glorious clear trumpet supported by the orchestra cheering him and finalizing this journey.

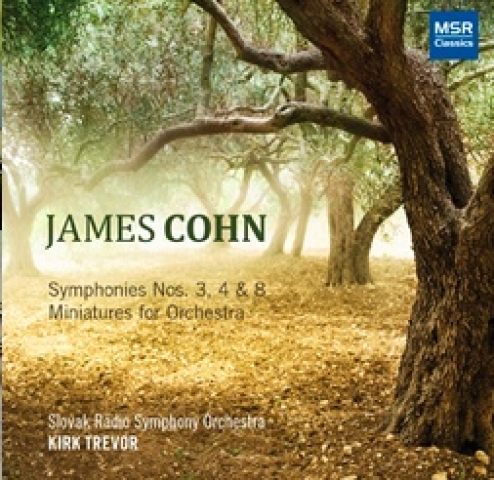

James Cohn established early in his composing the traditional orchestra setup in 1955 with his Third symphony. His orchestra creations create a clear, curious and potent energy. He has shaped this "musical era" into a marvelous personal sensibility.

Cohn's work is not nostalgic, but very present. It is often humorous in a way that Shostakovich is: Humorous with a touch of irony. He is buoyant but can also lay bare textural strands and the essence of a mood.

Does being accessible disqualify as a contemporary composer? Hardly. But a composer's dictum that music is to amuse may put critics off. The Cohn Quartet No. 3, premiered in 2015, is jaunty and melodic, as much as the composer's work is. Yet it is also musically complex, and stimulates the contemporary ear.

His Piano Concerto has a catchy and pointedly shaped motive of the opening piano theme. The theme is then offered as variations by the orchestra. This builds the movement’s narrative and reveals the whole spectrum of the theme’s nucleus. This unwrapping process brings us to an emerging fugatto in the middle of the movement, while the growing bravura exposition in the piano leads into the full orchestra.

He once again changes the sound picture. In breaking out of a neo baroque corner, he transforms the musical line into a very expressive wide romantic melody. He is determined to give his piano concerto a lyrical, Rachmaninoff-like signature.

More likely he is referring to many composers. Intense, pulsating feeling throughout this movement is influenced by the theme transposition through instrumental sections which creates the perpetual mobile effect. The music communicates with the listener and is very alive.

The Movement-Moderato-takes us through a pastoral experience. We hear Pan’s flute, innocence in the piano, a naive forest tinged with some doubt. That newly created pastoral environment is brought to life by reinterpretation of a pastoral topic as well as moving behind its surface, as some of the great post romantic and modernist composers did.

The third movement is in a form of a Tango. The gracious and leisurely style floats weightlessly, the entire symphonic orchestra is dancing a tango (bassoon, percussion section, brass) with the protagonist, the piano. Cohn’s solos always fascinate. The work is very emotional, spry, determined and young. His protagonist is young musically.

Cohn, an underexposed composer, deserves a close look, which promises to be a pleasant one. The composer succeeds in amusing, but not at the expense of serious music making.

In 887 the seductive story telling, wry observation and stage craft that calls on technical innovation and magic are there. The evening is all the more touching because it is Le Page's family story.