Alarm Will Sound at Carnegie Hall

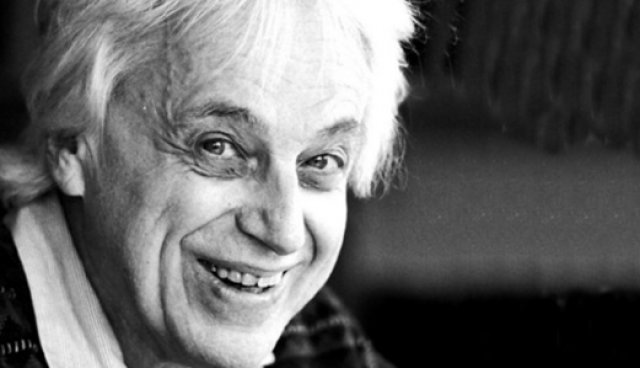

A Portrait of György Ligeti

By: Susan Hall - Mar 17, 2018

Alarm Will Sound

Alan Pierson, Artistic Director, Conductor, and Co-Host

Nadia Sirota, Viola and Co-Host

John Orfe, Piano

Steven Beck, Harpsichord

Zankel Hall

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

March 16, 2018

Alan Pierson of Alarm Will Sound invites us to a salon he conducts with Nadia Sirota. Tonight’s subject would be György Ligeti, the Hungarian composer who many people heard for the first time as they watched Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Nailing the composer’s name is the first subject. It is not George, but rather a juicy ‘j” and a gurgling “r”. These are not sounds or textures you hear in the composer’s music. Yet this complex, humorous name, like his often teased ‘lickety split,” bring smiles like his surprising music does.

We immediately join in the spirit of the evening. Our musical experience is going to be embedded in words, in a discussion of the man who has created this sequence of often thickly textured notes. How did they come to be?

Nadia Sirota repeats the evening’s mantra over and over. This music "should not have been created." Why? Ligeti’s life was always on the line, literally. It is difficult for an American to understand his living circumstances. A career as a scientist was taken away because he was a Jew. His father and brother were killed in the camps. He survived by accident. At first an enthusiast for Russian communism, he fled Budapest on a mail train, hidden under bags of correspondence with his wife.

His sound scape was inspired by radio programs which the Russians tried to block. Ligeti would go up his roof with radio in hand, and listen to the upper registers of broadcast music. The lower range was successfully cut off. Sounds of rockets in the air mixed with Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Three compositions were heard in their entirety. Continuum, a short composition, about which Ligeti said: “I thought to myself, what about composing a piece that would be a paradoxically continuous sound, […] but that would have to consist of innumerable thin slices of salami? A harpsichord has an easy touch; it can be played very fast, almost fast enough to reach the level of continuum […]. As the string is plucked by the plectrum, apart from the tone you also hear quite a loud noise. The entire process is a series of sound impulses in rapid succession which create the impression of continuous sound.” Steven Beck gave this plucked, rapid impression on the harpsichord.

The mathematics of fractals and chaos theory is one starting point in understanding the colorful and arresting Piano Concerto. Mixed in are individual and distinctive folk traditions of Africa, Indonesia and Eastern Europe. John Orfe at the piano almost miraculously brought forth the piece's many parts. Alan Pierson conducting held the beats of the chamber orchestra together.

The Chamber Concerto which concluded the program starts in the familiar territory of texture. As canons are unwoven in the last movement, melody and harmony return to the composer’s palette.

Lighting in Zankel Hall was dramatic. As we listened to music, our seats were in the dark, spots on the stage picking out musicians. When light was being cast broadly by words, the stage and hall were bright. During a performance of part of Ligeti's Poème symphonique for metronome, we could see old-fashioned metronomes held on high. During a performance Alan Gilbert conducted for select audience members, the metronomes did not wind down as they are directed to do. Yet you could understand why the Dutch TV broadcast of the Poème was switched from a world premier to a soccer game. The Ligeti we have some to know this evening must have laughed out loud.

Many people first heard Ligeti in Stanley Kubrick’s movies. Who can forget Ligeti's Lux Aeterna, the second movement of his Requiem and an electronically altered form of his Aventures? Kubrick’s use of classical music was breathtakingly original: the “stargate” sequence near the end—nothing more than a mosaic of brilliant colors rushing past—would have been completely ineffective without Ligeti’s dazzling sounds.

Although Kubrick's music was first used by Kubrick without permission, in Kubrick, Ligeti recognized "a willingness to explore and take risks, a tireless concern for detail and obsessive pursuit of perfection similar to his own.” When Eyes Wide Shut premiered in Germany, Ligeti accompanied Kubrick’s widow.

Ligeti wanted to develop a very thick polyphonic web. “I call it micropolyphony, because you cannot hear the individual voices. I wanted a new kind of musical color.”

Thomas Adès describes the essential quality that he hears in György Ligeti's music as the heat-death of the universe. It is sobering music to be sure, but also joyful. It is a pleasure to listen to Ligeti, the composer who survived beyond all probability. Near death experience helped him kick up his heels and write whatever he heard and thought. There is a joy in his mere survival. We were given a taste of it by Alarm Will Sound at Zankel.