Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress

The Boston Lyric Opera Production is Stylish and Sexy

By: David Bonetti - Mar 22, 2017

“The Rake’s Progress”

Music by Igor Stravinsky

Text by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman

Boston Lyric Opera

Boston Lyric Opera Ochestra

Boston Lyric Opera Chorus

Emerson/Cutler Majestic Theatre

March 12, 15, 17, 19

Conductor: David Angus

Stage Director: Allegra Libonati

Set Designer: Julia Noulin-Mérat

Costume Designers: John Conklin and Neil Fortin

Lighting Designer: Mark Stanley

Cast: Anne Trulove - Anya Matanovic (soprano), Tom Rakewell – Ben Bliss (tenor), Trulove – David Cushing (baritone), Nick Shadow – Keven Burdette (bass), Mother Goose – Jane Eaglen (soprano), Baba the Turk – Heather Johnson (mezzo-soprano), Sellem – Jon Jurgens (tenor), Keeper of the Madhouse – Simon Dyer (bass), Stravinsky – Yuri Yanowsky

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), arguably the 20th century’s greatest composer in the classical tradition, was a man of the theater, primarily of the ballet. He composed ballet scores throughout his career, from the early trio of folkloric works of pre-Revolution Russia, “The Firebird,” “Petrushka” and “The Rite of Spring,” the last a revolution in style and sound that totally transformed the decorous world of ballet, to the formal, more austere “serial” works of his late American period, namely “Agon”.

Even though – or maybe because - his father was a leading bass at the Imperial Opera in St. Petersburg, he was less comfortable with opera, producing a number of vocal works that awkwardly flirted with opera conventions, ending up more oratorios than anything else, stilted and stiff – hieratic - where his dance music was anything but. Until, that is, relatively late in his life when he collaborated with the celebrated English poet, W.H. Auden, on a full-evening three-act opera based on William Hogarth’s series of prints, “The Rake’s Progress.” The opera, which premiered in 1951 in Venice’s jewel-box opera house, La Fenice, was a highlight of a cultural season in a Europe still shaking off the ashes of World War II.

This inspired collaboration ended up creating one of the great midcentury works of music-theater, right?

Well, wrong. Despite the racy tale it tells – the moralistic story of a country bumpkin seduced by a slick-talking devil-surrogate who takes him to London where he falls without resistance into a life of licentiousness and corruption, ending his life in the madhouse known as Bedlam – it is dramatically inert, coming to life in only a couple of arias and, as a surprise and a relief, in the final moving scene. Stravinsky, nearing the end of his three-decade flirtation with neo-classicism, used Mozart as his model, primarily because Mozart eschewed the raw emotionalism that characterized 19th century opera, which Stravinsky professed to dislike. But Mozart, who exemplified the restraint and quest for order, clarity and balance of his era, packed more legitimate emotion in his operas in 15 minutes than Stravinsky was able to manage in two and a half hours with “The Rake’s Progress.”

Before I go on to explain a little more about why the work is such a dud, let me interject that the Boston Lyric Opera did it more than justice, creating a stylish and lively production with lots of good stuff to look at, notably tenor Ben Bliss’s chest, and assembling a cast that was full of attractive young singers and a celebrated veteran featured in a delightful cameo.

Stravinsky might have thought that he had the dream librettist in Auden, but the English ex-patriate brought along as his collaborator his boy-toy, an untalented poet named Chester Kallman who was better known for his pouf of blond hair than his skills at prosody. The story of Auden and Kallman’s relationship is sordid enough – the sexually aggressive Brooklynite threw himself at the older poet at a reading and they embarked on a long, and emotionally fraught relationship. Auden was besotted by the teenager - Kallman was an 18 year-old when they met - despite his constant infidelities, and was blind to his literary limitations. Kallman was an opera queen and he worked with Auden on libretti not only for Stravinsky but for the gay German composer Hans Werner Henze.

I cannot vouch for the quality of the latter, but I can say that Auden and Kallman turned out for Stravinsky one of the worst opera libretti any major composer ever set to music. There are too many words, many of them multisyllabic and high-falutin, and not enough repetitions, so the text goes flying by without time to take much of it in. (There is a reason traditional opera texts are so repetitious – on the third repeat even the most inattentive audience member might get it.) On the few occasions when they set a few doggerel verses straight out of the nursery (or the pub), you sigh with relief – silly, nonsensical, perhaps, but the little ditties are closer to what an opera text should be like than the pretentious philosophizing I suspect an intellectually insecure Kallman insisted on to show his seriousness. Stravinsky, setting words in his third language, after Russian and French, probably didn’t realize what a dead dog he was delivered by the leading British poet and his protegé.

Anyway, the text is often unmusical, the music and the words existing in two different worlds, seldom coming together. The first act starts out promisingly enough with some verses that actually rhyme and fall into classic forms, but the enterprise collapses in the interminable second act and catches itself only in the final 20 minutes, by which time many in the audience might no longer care, if they haven’t already walked out.

I suspect that Stravinsky, even working with Auden and Kallman, could have turned out a decent one-act opera, limning the quick descent of a not-terribly bright young man from the provinces in the sex pit of 18th century London, but they had to produce an evening-long three-act work for La Fenice, and as a result, they padded it – to deadening effect. I’d like to see an enterprising young company tackle the work, radically cutting and pasting what fine music Stravinsky produced into a shorter revision. (They could start by cutting the auction scene and the card game in the graveyard.) And Stravinsky did produce some fine music, you have to look (and listen) for it buried under the uningratiating verbiage. Ever the master of tart tonalities and pert rhythms, the score is peppered with wonderful ensembles for woodwind and even harpsichord. BLO music director David Angus found the right pulse and brought out the colors of the orchestration with sympathy.

Now back to Ben Bliss’s chest.

The production, led by stage director Allegra Libonati and BLO Artistic Advisor John Conklin, who designed the costumes here with Neil Fortin, was stylish, sexy and smart, although there were a couple of “additions” to the work that I think would have better been omitted (more on that later). Set designer Julia Noulin-Mérat created a time and a place that existed both in the 18th-century London of the original and in the 1940s Los Angeles Stravinsky lived in when he wrote the opera. The shifts from one to the other were for the most part seamless, although like any such mash up, you have to take a lot on faith.

OK, Ben Bliss’s chest. Opera singers today are often of a different order from those who came just a generation of two ago. Young and attractive singers are not hard to find, and young and attractive singers are not afraid to let you see how young and attractive they are. So here we come to Ben Bliss. A talented young tenor with a lovely light lyric voice, what one would expect from a grown-up choirboy, he is also good-looking and well-built. John Conklin seems to have accepted his torso as a Duchampian readymade – just show it for what it is, a gift.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a singer in a legit opera performance so consistently undressed throughout the production. (OK, there was Tom Fox as Jokanaan in “Salome” at the San Francisco Opera.) “The Rake” opens at the country home of Anne Trulove, where she and her boyfriend Tom Rakewell are cavorting in a swimming pool - this is an LA scene. Of course, Tom is wearing a bathing suit, and he flaunts, as any healthy young man might do, his attributes, namely a shapely chest and tight set of abdominal muscles. Tom’s studliness is supported by the text. His first aria, “Here I stand,” sung as he is about to leave for London, goes on to state, “my constitution sound, my frame not ill-formed, my wit ready, my heart light.” I don’t know about his wit – the opera doesn’t show Tom to be the brightest bulb in the chandelier, but the BLO does show his frame to be “not ill-formed.” Furthermore, Bliss’s body exemplifies the neo-classical ideal. Chaste rather than sexual, even in his scenes in Mother Goose’s brothel, it looks as if it was carved from marble by the neo-classical sculptor Canova. This might be one of the few times that the role and the actor are so close in essence as to leave no space between them.

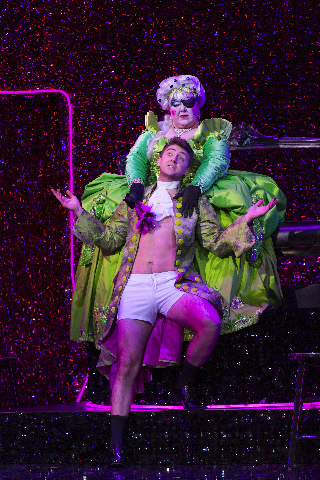

Once he gets to London, Tom keeps his shirt off. One of his first stops is at Mother Goose’s, which is the best scene in the production. Getting there he has to pass through a street gang of Roaring Boys. Dressed in purple shorts with braces, leather vests and black derbies, the Boys signal that this scene set in London’s demimonde, where Tom’s descent will begin, is going to be a rip-roaring experience. Once in the brothel, Lolita-like femininity takes over. The Whores – that’s’ what they’re called by Auden - are dressed in pink heart-shaped dark glasses with pink ribbons in their blond wigs. Tom appears in a long chartreuse brocade jacket, open, of course, to reveal his chest, and Mother Goose, a mountain of a woman, sits on a throne in a chartreuse gown. Tom gets lap dances from the Whores, and ends up sprawled in Mother Goose’s lap, her prize for the evening.

Conklin and Fortin deserve high praise for the color coordination in the scene. Everything is purple, blue, mauve and pink with sharp accents of chartreuse, black and red, a color scheme that continues throughout the production.

The scene shifts abruptly back to the country where a dejected Anne checks the mailbox to see if there’s a letter from Tom. This gives her the opportunity to sing the one extended aria in the entire opera, “No word from Tom.” Sung beautifully here by Anya Matanovic, it is the first time any feeling is registered by a character, a violation perhaps to Stravinsky’s neoclassicism, but something his model Mozart would not have had a problem with. At the end of the long aria, complete with cabaletta, Anne, wearing a tailored suit like a ‘40s movie star with long wavy hair to match, resolves to go to London to see what’s going on and to save Tom if that’s necessary.

She finds Tom in even more a dissolute state than she could have imagined. Bored – there’s a decadent scene of him in a gold bathtub and a gold robe, suggesting you-know-who - he has been convinced by his own personal devil Nick Shadow to marry the notorious Baba the Turk, the bearded lady. Their marriage scene is attended by black-clad paparazzi, and poor Anne, who arrives just as it starts, leaves, saddened and confused. More episodes occur, none necessary, but enough to fill the time expected by the La Fenice authorities and audience. Finally, after beating Nick in a game of cards, Tom is consigned to Bedlam, the notorious madhouse. This is another inspired scene, and Bliss, covered up this time (alas), sings a touching aria in which he likens himself to Adonis. “Mourn for Adonis, ever young, the dear of Venus: weep, tread softly round his bier,” he sings, breaking your heart even if Stravinsky didn’t want him to do so. Anne visits with her father, but leaves Tom to die with the denizens of the insane asylum.

After the opera appears to end, the principals reassemble on stage like the cast of “Don Giovanni” to offer a moral. Like the Hogarths that inspired Stravinsky, this is basically a morality tale, after all. “For idle hands/And hearts and minds/The Devil finds/A work to do.” For those who spent nearly three hours on this often tedious, unsatisfying work, other morals jump to mind: “Beware who you chose to collaborate with,” first among them.

Perhaps there should be another moral for the BLO: be careful embellishing a work with extraneous details. The BLO did a fine job with the opera, making it work better than it ought to have. But the company often turns out handsome productions and then casts them with inadequate singers – hey, there are only so many Jonas Kaufmanns in the world at one time, and even the Met has a hard time getting that guy to sing.

In this case they assembled a cast that was a pleasure to listen to as well as watch. Bliss and Matanovic both possessed light, flexible well-matched voices, making sonic sense that they would be lovers. Some might prefer singers with more weight to their voices – on Youtube you can hear Barbara Hannigan turn in a very different interpretation of Anne - but their voices were right in this pairing. And although Bliss and his bare torso got a lot of attention, Matanovic, who sang Violetta here a couple of seasons ago, was, although she kept her clothes on, his match in attractiveness.

As Nick Shadow, the man who buys Tom’s soul, bass Kevin Burdette, who has turned in intelligent performances for the BLO before, was appropriately slick, his mauve iridescent suit suggestive of a fancy used car salesman; his voice was as gravelly and insinuating as you would expect a Devil wearing mufti to be. As Baba the Turk, mezzo-soprano Heather Johnson, who sang here in “Lizzie Borden,” was a riot, turning a role that could be a grotesquerie into a sympathetic portrait of an artist making her living the best she can. As an example of luxury casting, Jane Eaglen, one of the great Brünnhilde’s of her generation, sang the Mother Goose. With only a few lines to sing, but making a great stage picture – Eaglen is a woman of amplitude – she showed herself to be above all else a good sport.

As Sellem the auctioneer, tenor Jon Jurgens, wearing a pink wig, was good, although I had tuned out by the time his big scene finally came around. And as the Keeper of the Madhouse, bass Simon Dyer, a BLO emerging artist, had a deep, mellifluous voice that was still able to make the words audible. As Trulove, baritone David Cushing was excellent as he always is in the small roles he is given. Isn’t it time someone mount a production with him at its center?

OK, now the complaints about the interpolations. The BLO has a tendency to look for greater meaning than is evident in the operas it presents, often some of the most profound works in the repertoire, which don’t need to be messed with. (Remember Senta sprawled on the stage during the early scenes of “The Flying Dutchman” or Pinkerton appearing in Cio-cio’s “dream” in “Madama Butterfly”?) Well, here stage director Allegra Libonati decided to include Igor Stravinsky himself as a non-singing character who walks around the stage sticking his nose in business he can’t change at this point. (If he could, maybe he could find something to cut.) For the most part, his presence was inoffensive, but it was also unnecessary and did nothing to add meaning to the work other than to show how clever the director was.

If having Stravinsky, played here by former Boston Ballet dancer Yuri Yanowsky, on stage from time to time didn’t hurt the opera, making Anne pregnant in her second visit to London and carrying her baby in the visit to the madhouse did – it was preposterous and inexplicable. Where did the baby come from? Did Tom knock her up before he left for London? Was her father, the only other male who appears with her, the baby’s father? These are questions you don’t want to have to ask, and you certainly don’t want the answer, at least to the second question.

In the future, I would caution the BLO to focus on getting the opera right on its own terms before going all German regie theater on us. You have to crawl before you can walk and you have to be able to walk before you can run. From what I’ve seen over the past seven years, the BLO is not able to run and at least half the time it’s not even able to steadily walk. Patience and modesty should be its motto.