Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints

Williams College Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 30, 2022

Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints

David S. Areford

Co-published by Yale University Press, New Britain Museum of American Art, and Williams College Museum of Art (2020)

New Britain Museum of American Art

September 18, 2021–January 9, 2022

Williams College Museum of Art

February 18–June 11, 2022

“In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art” Sol LeWitt wrote in Art Forum in 1967.

LeWitt (1928-2007) is regarded as among the most innovative abstract/conceptual artists of his generation. He died just months before the opening of a retrospective of 105 wall drawings in December 2007. They were created by technicians according to instructions. The works occupy a three story building on the campus of MASS MoCA where they will be on view for twenty five years. Recently, some of the works have been refreshed.

The LeWitt wall drawings were intended to be temporary but many museums have opted to make them permanent. As has Williams College Museum of Art where the exhibition Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints is on view through June 11.

The program of the prints is precisely that of the larger wall drawings. This is a compelling opportunity for immersion in the work. It is advisable to start with the WCMA exhibition. On a more intimate scale one gets a through grounding into the broad ranging aspects of LeWitt’s singular and daunting oeuvre.

He was a prolific printmaker with some 350 projects which in editions represents thousands of prints. That started at Syracuse University where he took a lithography course three times. He went on to explore many media including silkscreens, etchings, aquatints, woodcuts and linocuts. From seventy-six objects and series 200 prints are included in the most comprehensive survey of his prints to date.

The first works are expressive of the social realist and regionalist styles of the late 1940s. There is nothing particularly interesting about the examples on view. They are a starting point from which, after a hiatus, he abandoned for the pursuit of abstract and conceptual art.

After graduation, he found work and had little time for art. In 1970 he started with Crown Point Press and would go on to work with other printers and technicians. He worked directly on plates or had drawings and designs transferred to print media. There were even works created entirely according to his instructions. He was not satisfied with a project entailing art students as they took liberties in following his specifications. LeWitt insisted in the precise execution of his concepts.

The LeWitt plans, which museums and collectors own the rights to, have been compared to musical scores. But fabricators are not allowed the latitude of conductors.

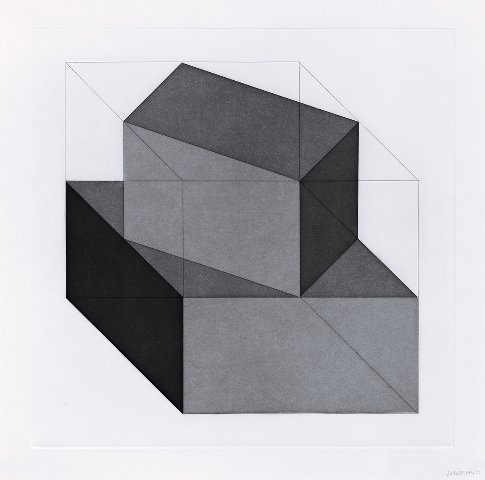

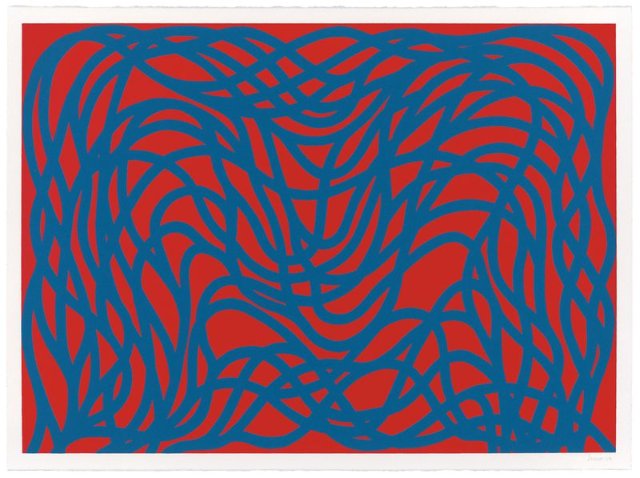

David S. Areford, who curated and wrote the catalogue, has presented the work by themes: “Lines, Circles and Grids,” “Bands and Colors,” “From Geometric Figures to Complex Forms,” and “Wavy, Curvy, Loopy Doopy and in All Directions.”

When LeWitt abandoned his juvenilia of figuration, he did not pass through abstraction but progressed to non objective art. The pioneering artists, Pabllo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian evolved from representation and abstracted nature. As Jackson Pollock stated “I am nature.”

By LeWitt’s generation artists were able to bypass the intermediary steps. In a sense he started with the suprematism of Kasimir Malevich. This is now generally the case with students emerging from ever more theoretical fine arts programs.

The generation of LeWitt and its aesthetic is well argued and dissected by Kenneth Baker in his seminal 1988 book “Minimalism.” The architectonic structures of LeWitt are discussed in that context. While aspects of the artist’s oeuvre relate to minimalism he evolved beyond its constraints.

In general this “movement,” the term was never used by the artists, stood on its head notions of the sanctity of hand made objects, the role of the art market, humanistic empathy, or conventions of aesthetic appreciation. Earth works and site specific works like Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” Walter de Maria’s “Lightning Field” or James Turell’s “Roden Crater” are in remote locations and cannot be owned by collectors through the conventional gallery system.

They are, however, supported by foundations like Dia. Initially Dia funded the Chinati Fundation in Marfa Texas where Donald Judd purchased an abandoned military base. There his works, and those of his artist colleagues, were fabricated for museum-like permanent display. We have made the pilgrimage to see that work as well as to Dia Beacon and the Dia rooms in New York.

By designing wall drawings LeWitt also deflected from the conventional gallery/museum paradigms. Currently we have the chance to appreciate the polarities of his practice with the gallery/ museum prints on view at WCMA and the institutional treatment of the conceptual, space consuming, semi-permanent wall drawings at MoCA.

Were it not for the artist’s status and perceived value the conceptual projects of LeWitt may well have languished in flat files at Yale as arcane documents.

Indeed Areford “Doth protest too much” by conveying in excruciating detail the precise program, instructions, and technical intent of every print on view at WCMA. This morphs beyond the study of iconography in art history which strove to explicate what a work of art means. His writing reflects the current way of looking at works of art which makes a case about evolving methodologies.

With the non-objective works of LeWitt there is no “meaning.” Some works, particularly when boldly geometric, or stridently graphic and brightly colored, have an immediate and visceral impact. Those with more opaque and complex ground rules are obfuscating and difficult to connect with.

There are essentially two ways to approach the WCMA exhibition. One might read each wall label and study the images, or sweep through the exhibition, letting our eyes do all the work of absorbing the experience.

Living close to the museum I enjoyed both approaches. For the first visit I focused on general impressions. At home I read the catalogue, then went back, read the labels, and studied each print individually.

The greatest incentive and joy of the exhibition is the opportunity to follow the artist’s thought process, as it were, from point, to line, to square. Another story arc is from the tentative, groping, initial works to the ever more passionately explosive and complex later ones.

In 1970 he started with drawing straight lines, then not straight, and not touching. A single etching plate was progressively rotated and reprinted. There is something very honest, readily comprehensive, and compelling about these images. That same year, at the age of thirty-four, his friend Eva Hesse died and he dedicated one of the first wall drawings to her. Compared to the strict and austere LeWitt, her inventive work was more humanistic and organic but they shared a commonality of intentionality.

An interesting midpoint work is “Shul Print (Six Pointed Star)” from 2005. It acknowledged his Judaism (he helped to design his local temple) while quoting from the small squares of color in the late Mondrian “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942).

In the final gallery a broad wall displays “Brushstrokes in Different Colors in Two Dimensions” 1993. They have a resemblance to the vertical stripes of Morris Louis. There is uncanny energy to “Wavy Lines (gray) and Wavy Lines (color)” 1995. which could be meditations on the futurism of Gino Severini and Giacomo Balla.

I plan to visit the exhibition again with a poet friend. Together I hope that we can unpack the enigma of Sol LeWitt. On another occasion Jim Jacobs, who deals in minimalism, and his artist wife Kathleen plan to fly in for a tour and discussion. This feels like an immersion in the work that may take years to spin out. Surely there are, and will be, scholars who spend a lifetime in study of such a densely daunting creator. In that sense he is like a contemporary old master.

A version of this article appeared in Boston's Arts Fuse.