Intimacy Direction/Choreography

A Relatively New but Growing Discipline in Theater

By: Aaron Krause - Apr 04, 2020

Even before the current strain of the coronavirus caused a pandemic, people might have established a threshold for what they literally considered “too close for comfort.”

Now, consider such a threshold in a post-pandemic world. For instance, folks may wonder: Is it safe to be in a room with a small crowd? A large crowd? Am I putting myself in danger if I shake a person’s hand? What about embracing someone?

Perhaps some stage actors might wonder if it’s safe for them to kiss as characters in a scene. For example, they might ask how close their lips should come to that of their scene partner’s. How should a director stage a full embrace if that’s what a playwright calls for?

In fact, some people may be unaware that, even before the pandemic, theater companies often employed a person to ensure scenes involving intimacy came across as convincing, seamless and safe.

Intimacy direction or choreography refers to creating and setting moments of intimacy. Particularly, these include instances in a scene that require personal vulnerability between characters, often involving physical contact. Chances are, after the COVID-19 threat passes, the role of the Intimacy Director/Choreographer will become even more important.

At least Nicole Perry thinks so. She is the resident Intimacy Director/Choreographer for the Sunrise, Fla.-based, professional Measure for Measure Theatre Company.

“I think we’ll be more conscious of touch and proximity,” she said.

And Daimien Matherson, Measure for Measure’s founder and artistic director, said he thinks it’s “extremely important” for theater companies to hire intimacy directors/choreographers.

“A role like this is vital to ensure the intimate moments are safe, believable and repeatable,” he said. “A role like this also makes sure consent always remains important and not just pushed aside.”

While an Intimacy Director/Choreographer may be “vital,” such individuals are relatively scarce in the U.S. Indeed, according to idcprofessionals.com, fewer than 50 certified professional Intimacy Directors/Choreographers exist in America. Perry is in the process of earning her certification.

Apparently, even those in the field use different terms for the position. In Perry’s case, she considers herself an Intimacy Choreographer when she’s working on a musical. For a straight play, she’s an “Intimacy Director.” Meanwhile, the “IDC” in idcprofessionals.com stands for “Intimacy Directors and Coordinators.”

“It’s very much about setting moments of intimacy safely and repeatedly,” Perry said.

What does Perry want audience members to know about her job?

“In some ways, I want audiences to know nothing,” she said. “If I’ve done my job well, you don’t know that I’m doing my job.”

The local theater artist said that, in general, that’s been the case. She added that people laugh at the fact that critics haven’t mentioned her in reviews. But she’s not about to become offended. Rather, she said the absence of her name in reviews indicates she’s doing her job well.

Perry began her theatrical career in 2010 in Philadelphia as a choreographer.

“I’m a movement person, I came from the dance world,” she said.

But at some point, Perry realized that, unlike fight direction/choreography, “best practices” for intimacy direction/choreography didn’t exist. Moreover, Perry began meeting like-minded people who also saw a need for such standards.

Around 2014, a group of individuals began talking about the lack of standards. Two years later, they created the now-defunct Intimacy Directors International. Meanwhile, around this time, people started becoming aware of such phrases as intimacy direction and choreography.

Perry began her training in May 2018, and officially became an apprentice in 2019. Now, she’s in the final stages of becoming certified in her field.

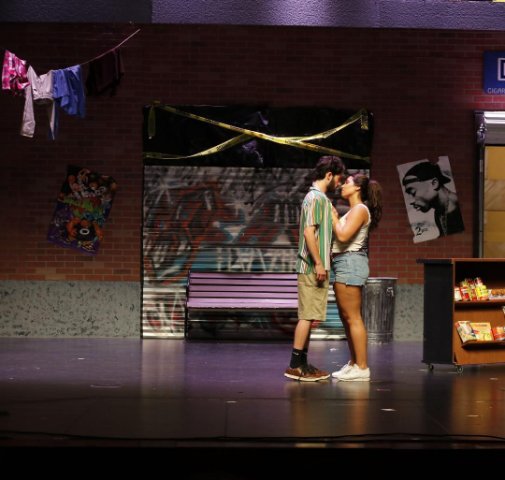

For Measure for Measure, Perry has worked on In the Heights, a musical about life in the Hispanic Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights. In addition, Perry choreographed scenes of intimacy in Island Song, a musical about five New Yorkers caught in a love affair.

Measure for Measure has had to postpone Island Song due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, she’s working on Rapture, Blister, Burn for Main Street Players. The Miami Lakes company slated the straight play for April 17-May 10, but has postponed it.

Perry is also working on her second show with Theatre Lab, the professional resident company of Florida Atlantic University. Matt Stabile, the company’s producing artistic director, called Perry an “exceptional artist.” And to illustrate the importance of intimacy direction to him, Stabile said that he and actor Niki Fridh are married. They were ready to perform in To Fall in Love, a production of which Stabile had to postpone due to the pandemic.

“Obviously there is already a significant level of trust between Niki and me,” he said. Nevertheless, “we knew this was the perfect opportunity for Theatre Lab to demonstrate our commitment to [intimacy direction].

“Nicole quickly provided us an easy-to-follow, set routine of movements which created the illusion of intimacy and allowed us to focus on the moment-to-moment acting work.

“Finally, she was able to provide Niki and I tips on how to ‘leave the work on stage’ and to make certain we weren’t bringing the issues and lives of these characters home with us.”

Matherson, the founder and artistic director of Measure for Measure, said that Perry “has been able to give more time, expertise, and attention to the small details that make intimate moments impactful and believable. I believe she has also strengthened our relationship with our actors. She’s given another level of comfort and openness that allow them to find a home with us and in their characters.

“Nicole has the ability to see and hone in on the smallest details that some may overlook. She is skilled at being able to adjust as she speaks to each person so they feel comfortable and she can get the best product from them. She has never-ending ideas of how to make the moments we are trying to create and how to make them work for each actor we have.”

One of those performers is Chris Alvarez. He has been acting for about four years. Alvarez has worked with Perry on In the Heights and Island Song. In the former, he played Benny, who is in love with Nina.

While working with Perry, “I learned on a deeper level how Benny’s insecurities affect him day by day, especially in his feelings for Nina,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Island Song, Alvarez will play Will. That is, once Measure for Measure proceeds with the production. As he worked in rehearsals with Perry on the song “Tie Me Up,” he “got to learn just how far the character’s goofiness, affection, naivete, and passion runs,” Alvarez said.

During her work with Alvarez and others on kissing scenes, Perry established a “1 to 10” scale. A “10” stood for an intensity suggesting the characters were going to get naked immediately Alvarez said. By contrast, a “1” suggested a “hello kiss to your grandmother.”

“Nicole also was very specific about pelvises touching on a kiss,” Alvarez offered.

Perry said that she believes her role in a production is to fulfill a director’s vision of a story “in a way that respects the actor’s boundaries and allows them to confidently do their job every day.

“A huge part of our job is not just creating movement, but creating movement the actor feels confident (about). And that confidence allows them to focus on the acting, which is what tells the story.

“(Performers) don’t have to be taken out of the moment by worrying about what they look like, what their scene partner is feeling, etc.”

Stabile said that nationally, people are more aware “of the need for and benefits of intimacy direction.”

In Perry’s blog, located at nicoleperry.org/blog , she writes that the coronavirus outbreak “raises questions that (people may not consider) when it comes to staging or performing intimacy in shows.”

For instance, what if a performer is sick?

In such a case, “Can we still tell the story effectively and well?” Perry writes. “As one of my mentors, Tonia Sina, reminds us, ‘Kissing is the most dangerous thing you can do onstage.'”

“Unlike stage weapons, the soft tissues and bodily fluids are quite real. It’s my job as the Intimacy Choreographer to develop this, not the actors’. It’s my job as the Intimacy Choreographer to rehearse, to make sure the actors are confident in it, and that tech knows what to expect if we go to Plan B.”