Timon of Athens at Cutting Ball Theatre

A Rarely Performed Shakespeare Play

By: Victor Cordell - Apr 08, 2018

Timon of Athens ranks as one of Shakespeare’s least performed plays. The many “Shakespeare Theater Companies” (believe it or not, the Bay Area has at least 12 variations on that theme) probably supply the bulk of its showings in order to complete producing the whole canon. So why did Cutting Ball’s co-founders, Rob Melrose (as director) and Paige Rogers (as artistic director), choose this troubled oddity as their joint swan song? Because, despite some obvious weaknesses, they saw strengths that could be amplified by Melrose’s script editing and by making the play more relevant to their audience. And they probably figured that if they assembled a remarkable ensemble of players and created a striking production that it could work. The outcome is a robust and rewarding event for serious theater goers.

The summary of the storyline starts with Timon being a rich gentleman who is extremely generous, regaling and often supporting his friends financially. Overextending his largess, he then suffers the misfortunes of poverty. Turning to his “friends” for assistance, he is rejected by all. “Nobody loves you when you’re down and out” (Jimmy Cox). Timon quits civilization and becomes a vengeful misanthrope. The end.

First, the knocks on Timon. An unfinished sense prevails as scenes and characters appear without adding value, so the play seems a bit choppy. This defect may be exacerbated by Melrose’s having excised large chunks of the play and by cast members playing multiple parts, so that it’s not always clear who they’re supposed to be. Also, while the dialogue is definitely Shakespearean, Timon lacks the popular quotes and hooks of the greater plays – no “pound of flesh” or “out damned spot” or “lean and hungry look” or “slings and arrows.”

Timon becomes a defeated idealist, which disheartens. The abject failure of his generosity and the callous desertion by all of his associates except one servant paints a depressing picture of society and noble intentions. In one extended series of metaphors, Shakespeare accuses all humans as being thieves or borrowers, albeit described with moving poetry, including the tract “The moon’s an arrant thief, And her pale fire she snatches from the sun….”

Title characters who confront challenges of extreme gravity inhabit Shakespeare’s tragedies – Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, and more. Timon’s conflict doesn’t reach the intensity of those murderous situations, but is closest to Lear. The dilemmas of both concern distributing their legacies, though the scope of Lear’s resolve carries kingdom-wide, while Timon’s acts are merely personal.

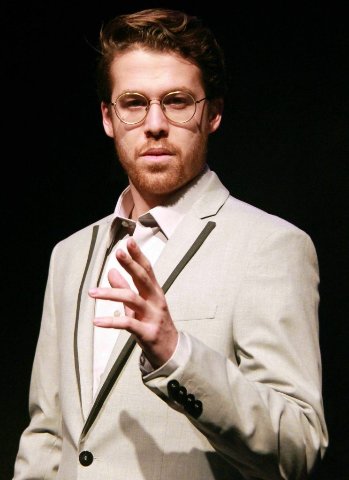

So what commends the play? Although Timon’s destitution is self-inflicted and his downfall matters little to the greater community, his quandary reverberates as it results from self-indulgence pervasive in society. Further, he is a powerful moral character. The role itself is compelling and calls for great acting breadth. In this version, Brennan Pickman-Thoon’s portrayal is stellar, at one point depicting a business-like but blithe adherence to the social contract with ramrod assurance and later, with reptilian writhing, revealing contempt and rage for the values and people who surround him.

Thematic elements are weighty and well presented. Cynically, or perhaps realistically, the two themes of friendship and money are interlocked in Timon, and their interrelationships are exhibited in two feasts that Timon hosts. In the first, when he is high on the hog, he gives a lavish dinner for all to attend, and he glows in adoration. After his rejected calls for financial assistance, he invites only four of his closest acquaintances, who salivate at the covered dishes on the dinner table. Climbing on the table, Timon unveils the dishes to reveal only water which he splashes on his guests with great disdain.

Melrose has cleansed the script of archaic vocabulary, making it more accessible. Brisk direction, movement, and abrupt location shifting within the black box energizes the action, resulting in slight loss of detail that is acceptable. He has placed the setting in the near future San Francisco, availing obvious linkages to the original script about homelessness and heartlessness as they affect us now. That said, and although Alina Bokovikova’s costumery is contemporary (and outstanding), nothing in the staging screams San Francisco. That is explicitly noted in the program. Michael Locher’s scenic design is simple but sleek and striking, capably using multiple egresses and all of the corners of the black box to extend the stage into the audience.

The acting throughout the cast is sensational. One highlight is David Sinaiko as the homeless Apemantus. In addition to expressive wide eyes, he incorporates lips, hips, fingertips, and all else into a notable full body performance. Douglas Nolan has some juicy moments as Ventidius and others. He howls and snorts with hyped up lasciviousness and delivers one of the play’s telling lines. Of Timon, he notes “Every man has a flaw, and honesty is his.” The other actors are riveting as well. Each delivers an outstanding performance with marvelous close-ups, and each deserves recognition – Maria Ascensión Leigh, Ed Berkeley, Adam Niemann, Radhika Rao, John Steele Jr., and Courtney Walsh.

Anyone with curiosity about this Shakespeare curiosity should see this realization of Timon. It is a meaningful play with much to recommend it. Supported by exquisite acting and directing, it is worthy and does as much as you can expect from a production of this problem play. The intimacy of the theater serves to intensify and enhance the rewarding experience.

Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare is produced by Cutting Ball Theater and plays at Exit on Taylor, 277 Taylor St., San Francisco, CA through April 29, 2018.

Posted courtesy of For All Events.