The Barnes Foundation Looks at South Africa

Sue Williamson and Lebohang Kganye Encourgae Remembrance

By: Susan Hall - Apr 11, 2023

Dr. Alfred Barnes, owner of the most highly valued art collection in the world, was often misunderstood. Yet his mission was always clear. Deeply democratic, he wanted to educate all people, of both high and low origins, to appreciate art.

When his collection moved from Main Line Merion to Benjamin Franklin Parkway in downtown Philadelphia, the doors were open to everyone. In the Barnes spirit, curators, security guards, cafe hostesses, cloak room attendants and visitors from across the globe are educated in the art that surrounds them.

A section of the Museum is dedicated to new traveling art. Curators are sensitive to making the Barnes Foundation of our time and yet continuing to display art in the Barnes tradition. Sometimes there are paintings that fall easily into the Barnes cannon. We look carefully at color, volume and line. Like the main exhibit area, comparisons and juxtapositions clarify our vision and make it more acute.

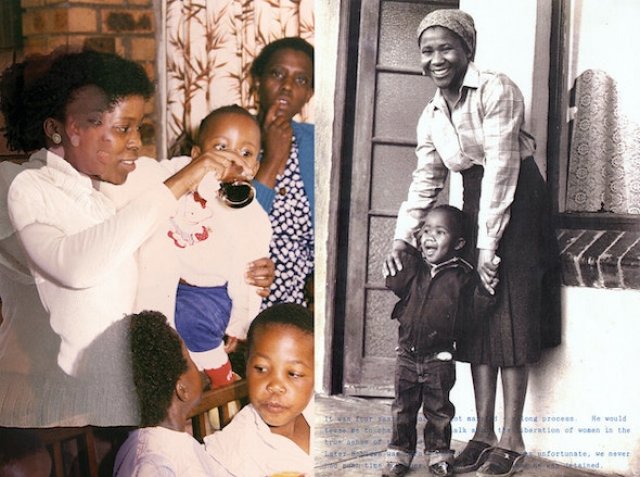

The current exhibit, on view until May 23rd, features two South African artists. One is white and in her eighties. The other is Black and in her thirties. Both artists look at women in apartheid South Africa. Truth and reconciliation in that country initially focused on men who were abused. Physical torture is easier to see than the emotional beating women take as their men are tortured and killed.

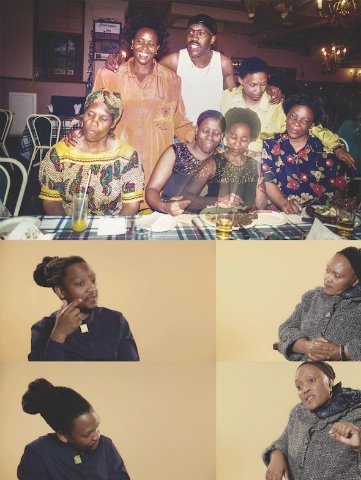

A striking video by Sue Williamson shows three members of a family–grandmother, mother and child- discussing the murder of the child’s father. The pressures of keeping the family afloat after the father was blown up kept the mother from sharing with her son who his father was and the circumstances of his death. Williamson films the interviews in a simple but warm background. The effects of ‘truth and reconciliation’ are clear, as the child warms to the mother who is dissolving the wall between them with the truth.

Williamson does not like to repeat herself. We know her as a printmaker, photographer and activist. She moved from England to South Africa when she was 7. She studied in the United States, at the Art Students League and other institutions. Then she returned to South Africa. There she became involved with other artists like Nadine Gordimer.

Gordimer has written that white artists in South Africa suffer from a deep identity crisis. They want to belong to the international world, and yet they are distant and isolated from it. They feel a new identity with the African Continent, but their way of life and social strictures make identification impossible.

Williamson has charged into this dilemma and in her art and illustrates an African world she clearly grasps.

Lebohhang Kganye comes to us in full Barnesian complexity. Not only do we see a world through the decorative gestures of classic African art, we also get to see various forms contrasted and merged. Stick figures form a tableau and then are animated on film.

Many such treasures are on display in the rooms of this exhibit. While Barnes at first resisted the ‘new’, his high school classmate, the painter William Glackens, who Barnes affectionately called ‘Butt’, supervised his education. Before they became known or popular Barnes relished Renoir, Cezanne and Matisse. He bought Modigliani and Soutine before anyone had heard of them.

The Barnes Foundation ended up under the control of Lincoln Univesity, a college for runaway and freed slaves founded in 1854. While Barnes was preparing for the supervision of his collection after his death, he had been charmed by Horace Bond, then President of Lincoln. He wrote to Bond "If we make an arrangement with you, it will give the world a chance to see that when given the proper opportunity, the Negro demonstrates that he has an intellectual capacity at least equal to the white man’s. ...His endowment for aesthetic appreciation is even greater than that of the average white man."

Visit the Barnes. Learn and enjoy.