Cosima Spender's Documentary Without Gorky

More Like Getting Over Gorky

By: Martin Mugar - Apr 22, 2012

“Without Gorky” a documentary about the family of Arshile Gorky made by his granddaughter Cosima Spender was shown this past Thursday at The Wasserman cinematheque at Brandeis to a large crowd mostly of Boston Armenians. Cosima was present and did a Q&A after the film.

Gorky committed suicide in 1948, when his daughters Maro and Natasha were still children. The story is about his looming presence in their lives to this day. This is a story about victims and victimizers and unresolved guilt. It has much in common in its format with Dominic Dunne’s TV “who done it” series of the crimes of the rich and famous “Power Privilege and Justice”.

The film’s premise is that something horrible if not quite a crime happened and seventy years after the event, the victims are interviewed and fingers are pointed at the guilty. Like a jury taken to the scenes of the crime, the mother, daughters, granddaughter and Spender from behind the camera visit the locations where Gorky and Agnes had lived from the Union Sq studio in New York to the Sherman Ct farmhouse where Gorky committed suicide and finally in at attempt to rise above the horizon of the family drama they all make a visit to the remnants of Khorkom near Lake Van in eastern Turkey where Gorky was born.

The documentary ricochets between the lofty and the petty and at times with the way it piques our love of gossip and voyeurism it might easily be serialized into a reality TV show like that of another metis Armenian family, the Kardashians.

The victims are Maro, Natasha and Agnes , although Agnes gets her share of criticism as a victimizer as well. She is a still stunning woman who radiates a kind of aristocratic hauteur, even in her late 80’s. Cosima, who hints at a not so easy childhood as the daughter of Maro, appears to be unscathed enough to be the disinterested observer of the crime.

I think she made this film as a catharsis to get over Gorky’s svengalian power to define the life of her mother and aunt. The film could have been entitled ”Getting Over Gorky.”

Both Maro and Natasha seem damaged to varying degrees psychologically in particular Natasha*. Just a toddler when Gorky committed suicide, she has no memories of her father, although upon a return to the Sherman CT farmhouse some long repressed memories resurface. Matthew Spender who wrote a book on Gorky interjects insights about him in the detached manner of an art historian talking about Gorky as the important art historical figure that he has become. At one point on a tour of Union Sq he comments about the way the urban environment inflected his work and at the end at Lake Van on the manner in which the landscape of his childhood gave him an endless source of memories and images that would nourish his work as an adult.

The film pointedly reminds us that when the family shared the same physical space, Gorky was an impoverished struggling artist. Family life was fraught with tension and possibly violence . “Mougouch” the name Gorky gave Agnes and which she seems to prefer, had pretty much abandoned any artistic ambitions to keep Gorky painting.

Agnes after Gorky’s suicide put both daughters in a boarding school for six months to travel around Europe with her lover Matta and Gorky’s friend apparently was more devastating to them than the loss of their father. In the end it is hard to place any blame on anyone still alive who lived with Gorky. Gorky’s deteriorating health, his old fashioned attitude toward women and the years of Agnes’ subservience to his goals finally absolves her of any guilt of abandoning Gorky before his suicide and her children for six months after his death, at least to this viewer of the film. The films strength is that it accepts the messiness of life and love and eschews the elegiac.

And how does Gorky fare?

He is not around to defend himself. We depend upon the words of Mougouch to know what happened. She describes him as a “full catastrophe” to use Zorba’s words for marriage. However, what seemed to hover around the edges of the film to its credit and that transcends the often pathetic gorging on the reputation of being a “Gorky “ is that something larger than life happened when Gorky and Agnes met.

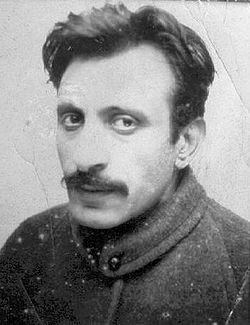

On the surface he was a handsome bohemian with a reputation for being an exotic, who would save Agnes from her predictable destiny as an upright flower of Yankee culture. But beneath the surface was his history, which she wasn’t prepared for . Gorky was a man with a destiny that he had to live out. The shared life could not help but be explosive. On the one hand was a need to work out all the disparate influences he has absorbed from Picasso, Miro, Kandinsky and the Surrealists and that lead many of his generation to see him as talented but unoriginal.

On the other hand those mysterious years of his childhood are a mystic source that he feeds on for the rest of his life. They are so sacred that he hid them from everyone, including his wife. It was a sacred font that he has to honor and cherish in the way he cherished his mother’s memory in those evocative paintings he did from the photograph of him and her. Because he could never share similar emotions to anyone close to him, it marred his marriage to Mougouch.

I also see in Gorky an another example of a wild Armenian type that I have met on occasion, for example the artist Varujan Boghosian, and photographer Arthur(Harout)Tcholakian. Stories I’ve heard about Saroyan , Gurdgieff and the filmmaker Parajanov seem to point to a crazy Armenian type that is full of spontaneity and with a Zorba-like predeliction for the unpredictable. They reach beyond the rational to the creative power of the irrational. A quote from Kazantzakis seem apposite here:

Alexis Zorba: Damn it boss, I like you too much not to say it. You've got everything except one thing: madness! A man needs a little madness, or else...

Basil: Or else?

Alexis Zorba: ...he never dares cut the rope and be free.

Watching a documentary one is lulled into the belief that what we see is fact when it is just part of a storyline.

I sensed this when I watched “HarvardBeats Yale 29-29” about the classic game in 1969 where Harvard comes from behind to tie what looked like a certain loss.( I attended that game,which claims twice the number of attendees as seats at Harvard Stadium) The story is based on interviews with the players about their recollections of the game some 40 years later.

Yale player Mike Bouscaren turns his experience of the game into a transformative story of how he learned to get beyond a grudge match against Harvard’s Hornblower so as to finally see the opposition’s humanity. It fit nicely into the background references to the ongoing Vietnam war and the machismo that lead American into the war.

By the same token Natasha’s forlorn look played into the theme of victim and victimizer and as wirh Bouscaren’s case, in the end it may not be factual.