Kumiko and the Journey into Dreamerhood

Film by David Zellner Riffs on Fargo

By: Christopher Johnson - Apr 27, 2015

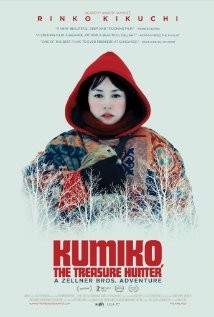

David Zellner’s “Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter” is not an unseen phenomenon in US cinema. But in taking the true story of a Japanese woman, Takako Konishi, who went looking for the money that Carl Showalter (Steve Buscemi) hid in “Fargo,” and fictionalizing that story, the filmmakers (David Zellner and Nathan Zellner who wrote and starred in the film) create a constant vacillation between truth and fiction. An unnamed deputy/sheriff (David Zellner) who helps Kumiko (Rinko Kikuchi), or tries to, through some of the second half of the movie attempts to explain the difference between documentary or news footage and “normal movies”; ironic with the fact that Zellner is probably well-versed in many strands of film types through its history.

Another curious thing is expressed in the painfully awkward situation with the deputy and Kumiko where he says there’s a cultural divide between them and he’s absolutely sure that in the Japanese culture what Kumiko wants to find (happiness, money, definitely not a husband as her mother keeps harking her to get) is extremely important. In fact, if a US citizen tried to go find the treasure from “Fargo,” they’d be institutionalized post haste. The film, in this sense, is a clever little parable about the status of dreamers in the modern world. After recently hearing it sampled in an album, I can’t help but thinking of one of the characters the Dreamer meets in Richard Linklater’s “Waking Life,”: “They say dreaming is dead, no one does it anymore. It's not dead it's just that it's been forgotten, removed from our language. Nobody teaches it so nobody knows it exists. The dreamer is banished to obscurity.”

The whole film is a kind re-creation of “Fargo” with the bleak, midwestern landscapes and the talk of the people which was fashioned very precisely to how people spoke at the ambiguous time of the turn of the century. The camera is slow; comparing a film’s movement to a river’s was a metaphor Kurosawa stole in describing Satyajit Ray’s films but this is one film that I think deserves that description. Except it is a river without a destination.

This film isn’t easily brushed away as playful or fun; there’s a lot of suffering. Konishi’s death in the Minnesotan winterscapes was ruled as a suicide. We get an extremely frightening moment when Kumiko runs away from everything else and is in the night, very far from any other human being, with only a flashlight and a blanket she stole from a hotel to protect her. We get flashes of the beam of light hitting the viciously pelting snowflakes for what feels like a terrifying five minutes. In reality it was much shorter but it looks like a Marie Menken film since the camera had largely been steady throughout suddenly becomes manhandled and we get put into Kumiko’s perspective in her last moments.

Like in “Fargo,” the film doesn’t have a lot of color. Kumiko is the center of the color throughout the entire movies, with her red sweater and multicolor blanket. Curiously, the scene we see repeatedly from “Fargo” is when Buscemi has already been shot through the cheek and is hiding the money. In a parallel scene, Kumiko tries to dig what she thinks is money out of a frozen lake, ending up bleeding and pulling out a log instead of a suitcase.

The film is a kind of warning to the dreamer but at the same time an encouragement. It also asks us to consider the strange world we would live in if everyone took everything in fiction films as fact.