2012 Norton Prize Winner William Kentridge

Animations at Harvard Film Archives

By: Nelida Nassar - Apr 30, 2012

William Kentridge, the South African artist, filmmaker, theatre and opera stage designer is the 2012 recipient of the Elliot Norton Prize. His drawing-based art practice uses primarily charcoal, a touch of blue and red pastels, printmaking as mediums and age-old techniques to create often fiercely political and cutting edge work. The basics of South Africa’s socio-political condition and history must be known to grasp his work fully. He is a visual chronicler, much the same as artists such as Francisco Goya and Kätheh Kollwitz.

Monday afternoon, while Boston was aquiver with its annual Marathon, Mr. Kentridge, under the rubric Six Drawing Lessons, delivered his fifth of the six Norton lectures. Following the lesson, the Film Archives at the Carpenter Center projected nine of his animated films – five from 9 Drawings for Projection, (Mine, History of Main Complaint, Weighting and Wanting and the Stereoscope) made between 1989 and 2003, and four stand alone animations (Memo, Ubu Tells the Truth, Journey to the Moon and Other Faces).

Memo (1994) is a remarkable polyptych, mixing pixilation with a drawn technique and frame-by-frame animation. Its theme is the concept of Time, its passing, the traces it gives away, and the memory that beings, events, and objects leave when we ignore our past. Incidentally, Mr. Kentridge’s obsession with the theme of Time is not new and has pervaded his work from its onset. For the last couple of years, he has been engaged in a conversation with the Professor in History of Science and Physic, Peter Galison about this unrelenting preoccupation. This is also the research subject that he will present next week during his sixth drawing lesson.

Kentridge began doing animation with the 16mm, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris. While this film introduces us to Soho Eckstein, his wife and her lover Felix Teitlebaum, Mine, History of Main Complaint, Weighting and Wanting and the Stereoscope chronicle Eckstein’s ongoing story – the artist’s alter ego. Soho is a corpulent, bald, pinstriped, archetypal white Johannesburg industrialist, or real estate magnate, of the post apartheid era. He remains ignorant of his repression and the subsequent political upheavals around him; he is more concerned with the affair between Mrs. Eckstein and Felix. The evocative, allegorical narratives blur, smear, mutate and coalesce in a visual flow of consciousness punctuated by recurring motifs: mid-20th-century office gear like Bakelite rotary phones, adding machines, and ink blotters which morph into the forgotten black bodies of company workers and the people of South Africa.

In Mine (1991), Soho Eckstein is depicted as a minerals magnate at repose and dreaming. His bed morphs in to a desktop with the appearance of a French coffeemaker. When Soho depresses the coffeemaker’s plunger, he inadvertently initiates a journey to the center of the earth, into the mine. Here the mine becomes a metaphor for our anxieties, our aspirations and our thinking. Kentridge’s mark-making and erasures unveil strata of artifacts, bodies, and things. The mine asks: “How shall we explore and exploit our history?” To which Kentridge reply is “That we must depict it so we can see it, but then we must immediately alter it.”

In the six-minute film, Weighting … and Wanting (1998), Soho is more introspective. He longs for contact, commiseration and love, none of which he seems to achieve.

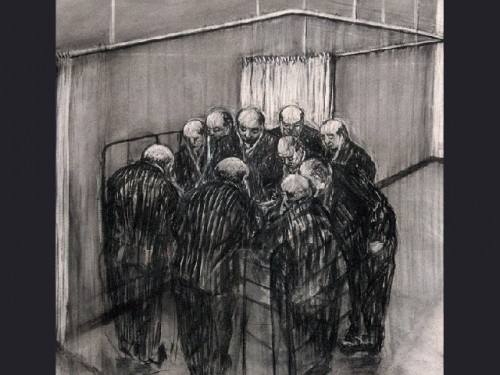

History of the Main Complaint (1996), is Kentridge’s impassionate response to the collapse of apartheid in South Africa and the subsequent state of South African society. The film exemplifies his personal reaction to the existence of a “brutalized society” where he attempts to delineate its fragile state as embodied by the cigar-smoking Eckstein’s health and hospital stay that seems as tenuous as the social order he inhabits. The film exudes an eerie sense, a ghostly alienation and hopelessness.

Journey to the Moon (2003), is a tip of the hat to the great French cinematographer Georges Méliès, where in 7 Fragments, we see Kentridge comically climbing a ladder on one screen (and tumbling down), pacing on another and ripping apart a life-size drawing of himself on yet another. He elicits several jokes by running the film in reverse. An invasion of his studio by ants entices him to lure them with sugar cubes, thus creating a negative image of white flecks on black.

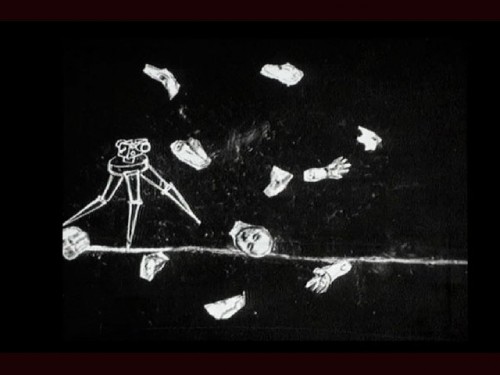

Ubu Tells the Truth (1997) was made in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that South Africa established to sort out the crimes of the apartheid era. Kentridge brings to life Ubu Roi, an Alfred Jarry character and one of the most monstrous and astonishing theatrical figure in French literature. He uses an actor’s black silhouette, as well as hand drawn animation, showing his astounding power of improvisation skills.

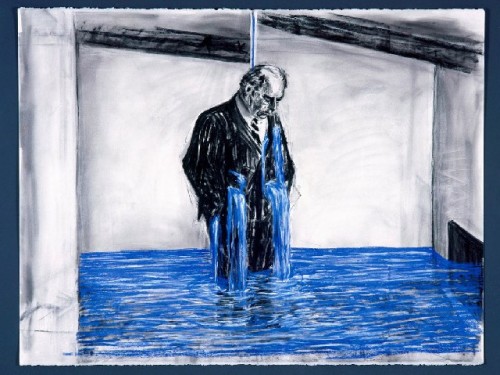

In Stereoscope (1999), while Soho sits at his desk looking at a framed photograph of his wife, she comes to life with her lover, Felix Teitelbaum. Crowds gather outside Eckstein’s house, his office building eventually disintegrates in a cloud of charcoal dust and Soho, head bowed, stands alone in a room. Kentridge’s blue stream lines begins as sound lines that connect the quickening pace of telephone ringing, cat screeching, wheels turning and churning that, in the process, cause a tower to fall down. They soon change when the inconsolable Soho, sobbing, finds himself standing in a rising bright blue pool of his own sadness and grief. The sound spurts of bright blue are now transformed to suggest water – a reprise against affliction but also tears.

In Other Faces (2011), Kentridge’s latest animation, Eckstein is involved in a car accident with a black preacher in front of a black African church in downtown Johannesburg. The argument soon fades through Kentridge’s drawings animation, layering, and erasures, leaving Soho to his own recollection of the event. Kentridge’s narrative and impressionistic contemplations are more a reflection on the fractured, individual understanding Soho and the preacher each have of their country. It vacillates between contradictory recollection, the relationship of the city and its suburbs, the races and its inhabitants, the shift in power, the fiscal imbalance of credit and debit, and the changing crowd from an enveloping symbolic presence to a real, threatening one. Throughout the animation, Kentridge examines the dichotomy between these paradigms while simultaneously representing Johannesburg’s black population as embittered, oppressed and subjugated. Other Faces is yet a new attempt at redefining our understanding of Post-Apartheid and Johannesburg.

The animated films vary in length from four to eight minutes. Each is based on a series of some 60 to 80 charcoal drawings, mostly in large sizes, with some enhancements in pastels that take one year to complete. In a desire for a chromatic simplicity with symbolic values – and to contrast against the subtlety of gray – only colors, such as blue to represent water, and red are used.

Another feature of Kentridge’s work is a technique of successive charcoal drawings, always on the same sheet of paper, contrary to the traditional animation technique in which each movement is drawn on a separate one. The images are constructed by filming a drawing, making erasures and changes and filming it again. In this way, Kentridge’s videos and films keep the traces of the previous drawings. This process is quick, and reflects almost impulsive sketches, ephemeral charcoal smudges, fragmented lines and movement. Kentridge continues this process meticulously, giving each change to the drawing a quarter of a second to two seconds of screen time. A single drawing will be altered and filmed this way until the end of a scene.

Since the late 1970s, refusing any computerized special effects, Kentridge has concentrated on the direction of “moving pictures.” He has crafted deliberately primitive and profoundly imaginative films based entirely upon his handmade charcoal drawings and, using only a drafting table and camera, refining them gradually. Kentridge’s technique itself is not entirely unique – Oskar Fischinger made “motion paintings” and charcoal-on-paper animation as early as the 1940s, as well as Oscar Schlemmer at the Bauhaus. But, while Kentridge displays a distinctive style in his films, there is the occasional nod to other artists he admires – the films of Georges Méliès and Sergei Eisenstein, Cocteau’s “Blood of a Poet” also comes to mind, as does the famous scene in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Two or Three Things I know About Her.”

The artist incessantly repeats his feelings of failure. “I’d failed as an actor, as a painter, and I’d kind of failed as a filmmaker, in a different way. Existentially, it felt like one dead end after another. I thought, I’m useless, I’m no good, I’ve got nothing to say.” This is truly a surprising statement from one so talented. Kentridge, like the German neo-expressionists Anselm Kiefer and Jörg Immendorff, is capable of giving life to all that has never been admitted in art, embodying all the torment and the labor the creator draws upon to make a work of art. With significant compassion, humor, and willed innocence, Kentridge examines the external and internal forces that shape us as human beings.