Ethiopia: Part One

Addis Ababa, Aksum, Lalibela

By: Zeren Earls - May 01, 2020

In late February, I traveled to Ethiopia before the coronavirus had reached the African continent. Joining a group of 15 others, I took a 13-hour direct flight on Ethiopian Airlines from Washington, DC to Addis Ababa, the capital city, located at 7,700 feet above sea level, where over 3 million of the country’s 128 million people live. Ethiopia is Africa’s most populous country, with 83 ethnic groups speaking 74 languages.

The crowded airport with very slow-moving lines for passport clearance in Addis, as it is known locally, and the subsequent mini-van ride were indicative of the country’s limited resources. The van made its way through traffic, competing for space with cars, tuk-tuks, donkey carts and people on their way to church for Sunday service. Upon reaching the Radisson Blue Hotel, our home for the next four nights in the heart of the business district, we had to clear security to get in. The hotel lobby offered a welcome serenity to the bustle outside. My 8th-floor room with a view of the city offered the comforts of a much-needed rest following the long journey from home.

Although Ethiopia has an illustrious history, the civil war with communist sympathizers in the 1970 s and 80s and the long-lasting border dispute with neighboring Eritrea more recently have left the country impoverished and impeded its development. Our afternoon walk in the vicinity of the hotel, including the weekend open air market, accentuated the visible poverty. Along uneven sidewalks, makeshift stalls loaded with used clothing and tools attracted bargain hunters, while blonde mannequins imported from China beckoned with traditional wear. Food vendors squatting on the ground roasted various grains and seeds. We stopped for a break to taste Ethiopia’s famed coffee, always made from freshly roasted beans and served in demi-tasse cups.

Our second day in Addis coincided with Adwa Victory Day, which commemorates the defeat of an Italian military occupation in 1935-1941. People adorned in the colors of the national flag – green, yellow and red – filled the streets, all moving in one direction toward the city center to hear a staged address by the Mayor. As they walked, impromptu mock battles broke out. Due to the massive size of the crowd, our group could not reach the stage.

In the afternoon, we drove through narrow dirt roads up Mount Entoto for a panoramic view of Addis Ababa, which means “New Flower” in Amharic, the official national language. Then a tour of the sprawling city included some of its cultural treasures, such as the National Museum, a showcase of Ethiopia’s history. Among the exhibits are plaques in recognition of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2019, and the remains of early hominids, including a replica of “Lucy,” the 3.25-million-year-old skeleton discovered in northwestern Ethiopia in 1974 (the original is under lock in the museum).

Another treasure is the Ethnological Museum, which occupies two floors of the palatial residence of Haile Selassie and covers Ethiopia’s cultural and social history. Exhibits show the diversity of the country’s ethnic groups with musical instruments, dances and costumes. According to a wall text, the word “Ethiopia” comes from the Greek “Aethiops,” which means “the land of burnt faces,” as the territory south of the pharoahs’ empire was called.

Our unique experiences included a visit to a rehabilitation center for people with disabilities. Here, following a three-month training period, people with disabilities learn skills for marketable products, such as grinding glass for eye wear, weaving shawls on a hand loom and even sewing with one’s toes. I watched a young girl embroider a flower on a greeting card with her toes – amazing. I bought one of her cards.

Known as the largest market area on the African continent, the Addis Mercato is a vibrant open-air sprawl of vendors that goes on for miles. Donkeys scurry around; men carry unimaginably heavy loads on their heads. Here bargaining comes with the turf; it is customary to offer half the asking price and end up somewhere in between.

Visiting a coffee processing plant was our last activity in Addis. Ethiopia is coffee’s ancestral homeland, where the plants grew wild, before cultivation started 1000 years ago. After enjoying a cup of coffee at the plant, we watched workers roast, package and seal the beans ready for the market, where a one-pound bag sold for about $4.

Early the next morning we flew north to Aksum, one-time capital of the ancient Aksumite Empire, whose influence stretched over northeast Africa and southern Arabia from the first to the seventh century AD. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, now Aksum is home to reminders of its glory days.

Our sightseeing began with colossal obelisks erected to mark the tombs of kings and nobles of the Aksumite civilization during pre-Christian times. More than 120 of these intricately carved monolithic pillars are scattered throughout the region. One of them, more than 100 feet tall and weighing 520 tons, fell over and shattered as it was being erected in the fourth century, damaging a very large megalithic tomb with a capstone weighing 360 tons. This damaged tomb, with two portals and one central passage, houses ten burial chambers, five on each side, with three shafts to allow light and air underground. Precious materials were buried alongside the deceased nobles.

The next cultural stop was Saint Mary of Zion Church, a religious complex dating from 1665 and thought to rest atop the foundations of a temple built in the fourth century, making it the oldest Christian site in Africa. It is believed that a small chapel located here contains the Ark of the Covenant, a gold-covered acacia wood box where Moses is said to have placed the stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Guarded by a succession of monks, who serve until death, the room is closed to all. Outside we observed a Lenten procession of the devout; women, men and children, all wrapped in shawls of white gauze, followed priests in golden robes carrying ceremonial umbrellas and crosses as they circumambulated the church three times, chanting. The ceremony ended with the blessing of the crowd by the Orthodox priests.

A trip to Yeha, an archeological site 35 miles north of Aksum, introduced us to rural life in Ethiopia. We drove by fields of teff, the grain used to make injera, a spongy flat bread that is a staple of every meal; waved to children walking long distances to fetch water or firewood; and admired the erect postures of men carrying heavy loads on their heads. Mountains emerged as we approached the village of Yeha, considered to be the birthplace of Ethiopia’s earliest civilization. A migration of southern Arabians from Yemen into the Tigray region led to a synthesis of Arabian and African cultural elements. Yeha was the political and religious center of this merger since the early 1st millennium BC.

Volcanic rocks form the mountains around Yeha, which is still inhabited by villagers. The archeological site of a series of ruins includes the famous Great Temple, once the administrative center of Yeha. The German Archaeological Institute is assisting in the restoration. A small museum housing stone-carved inscriptions and Christian ritual objects and books, as well as treasures of a still active historic church, enhance the visit to the site. Manual subsistence farming is the predominant lifestyle of the villagers. We watched the first few minutes of a four-hour ordeal of a blindfolded camel extracting oil from sesame seeds by walking around a stone grinder.

On our return to Aksum, our home-hosted evening meal presented a very different way of life. On a quiet street we visited a two-storey house with a roof terrace complete with water depot. We enjoyed dinner on the spacious outdoor patio, carpeted with flowers from the garden and decorated with local crafts. The owners were away on business; we were hosted by their sons, one of whom ran a gift shop at the airport. A cook had prepared a variety of local dishes, which were served with injera bread. Coffee along with popcorn – a customary accompaniment – completed our meal. As we bid farewell, my host invited me to stop by his gift shop on our way to Lalibela the next morning. I happily obliged.

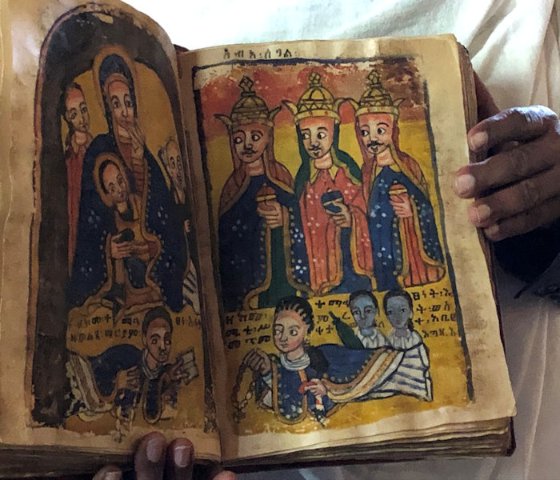

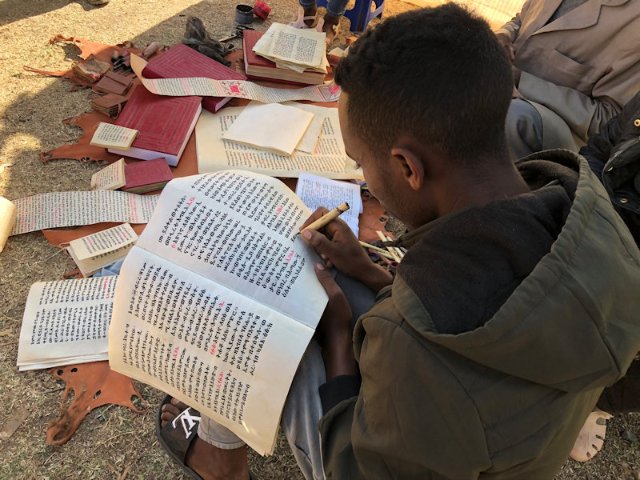

Religious devotion dominates daily life in Ethiopia. In Axum, we observed people waiting early in the morning to get into the courtyard of a church where services are often held. A visit to a family in the business of hand-written books further exemplified this devotion. We watched a young man in training use bamboo pens to write meticulously on paper made from stretched, shaved and dried goat skin.

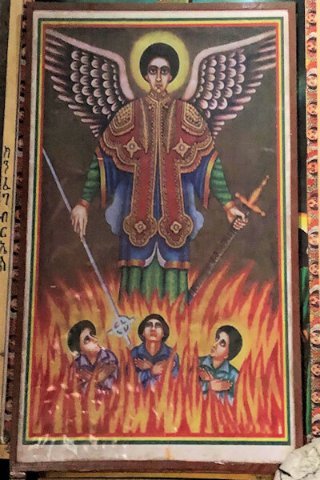

Lalibela, named after its 12th-century king, is a mountain town 200 miles south of Aksum. A 45-minute flight saves time and hassle negotiating mountain roads to an altitude of 8,500 feet. The wait time in the departure lounge allowed us to browse through a variety of gift shops, tempting me to buy two items – a T-shirt and a colorful hand-woven basket. The red T-shirt features the image of the protective angel one encounters frequently in Ethiopia. Winged angels with prominent almond-shaped eyes appear in churches, homes and restaurants, and on boats and anything else deemed to need protection. Happy to have my protective angel with me, I boarded the plane.

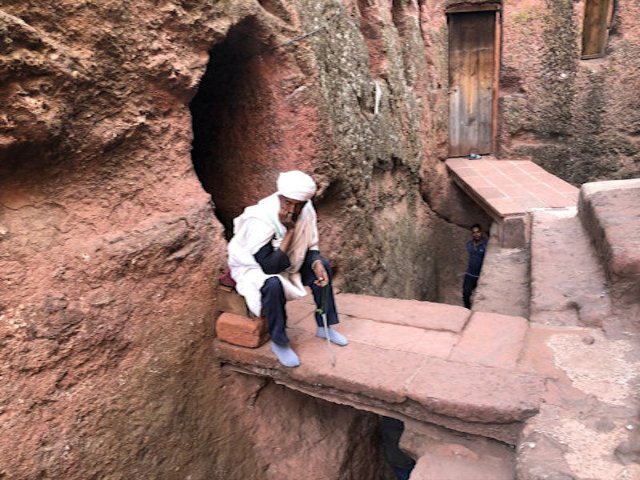

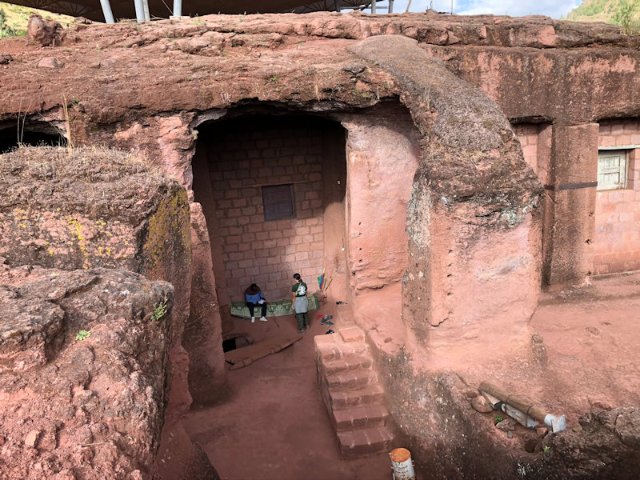

Lalibela, a UNESCO World Heritage Site considered a very important place in the Christian world, is home to 11 Ethiopian Orthodox churches carved out of a single volcanic rock some 900 years ago. Legend has it that the churches came to King Lalibela in a dream that urged him to create a new Jerusalem out of the solid rock where the town sat. Connected by ceremonial passageways, some of the churches were chiseled top-down from a single rock, with carved-out roofs, doors, windows, columns and drainage ditches; others stand as isolated blocks.

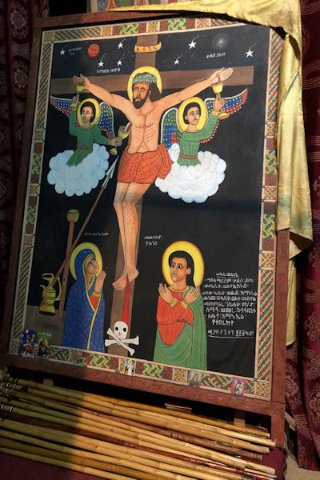

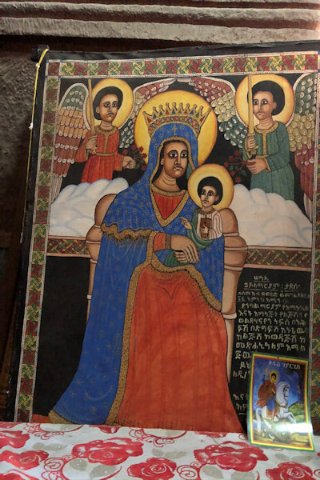

The complex is divided into two groups of churches, with one cluster representing the earthly form and the other the heavenly form of Jerusalem. In our sock feet and with women’s heads covered, we walked back in time, bent over not to hit our heads as we passed through tunnels connecting the churches, visiting each group on a different day. The dimly lit small interiors are packed with religious icons and paintings, some of which appear on columns and ceilings; all the churches are active and attract pilgrims daily.

At the end of our first day, following our visit to the first group of churches, we were rewarded with a beautiful Ethiopian sunset as we enjoyed locally farmed food at the hilltop Ben Abeba restaurant. The contemporary design of the restaurant features multiple decks, spiral staircases and walkways, giving patrons 360-degree views of the expansive Lalibela valley below.

The following day, a scenic 1½-hour drive through the countryside took us to Yemrehanna Kristos, an ancient cave church which predates the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela by almost a century. It took another 15-minute hike up a steep hill to reach the cave and the unique church built of stone and wood, at an altitude of 13,000 feet. Over the centuries some 10,000 pilgrims have come here to die; their bones rest in a pile behind a screen at the back of the cavern.

On the way back for lunch, we walked through the vibrant, informal Lalibela market, crowded with vendors under individual umbrellas for shade with their goods spread on the ground. Some sold sugar cane, which people bought to chew despite its harmful effects on their teeth. A donkey market, equally crowded, occupied a separate area.

In the afternoon we visited the second group of rock-hewn churches, which were carved from a sloping rock terrace; they too pay homage to sacred sites in Jerusalem. On the way we encountered many pilgrims, who believe the churches offer the same blessings as those in Jerusalem. Each year 80-100,000 visitors come to these churches.

On our third and final day in Ethiopia’s holiest city, we visited Asheton Maryam (Saint Mary), a small rock-hewn church set on a mountain overlooking Lalibela. To reach the church, we rode mules uphill for about 45 minutes, then hiked up steep terrain for another 45 minutes to reach the summit of Mount Abuna Josef, at an altitude of 13,000 feet. The small church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is carved into the vertical cliff face. The six of us who made it to the summit were rewarded with vistas of the surrounding scenery and treasures such as ancient books, paintings and icons of one of the highest monastery churches in Ethiopia. Afterwards we hiked down the mountain to meet our vehicle.

The day’s final visit to a rock-hewn church was to Bete Giyorgis, the Church of Saint George, named after the patron saint of Ethiopia. The best preserved and most famous of the Lalibela churches, Bete Giyorgis is a stand-alone church hewn out of the volcanic stone landscape by builders who carved downward as they went, hollowing out the interior. Dating from the late 12th or early 13th century, it is instantly recognizable as a giant walk-in cross in a deep pit. The church also features three hand-carved doors and twenty windows.

A home visit, where we learned how to make injera, was the final activity of our day. We enjoyed dinner prepared by our hostess and accompanied by our freshly baked bread. The customary coffee ceremony topped the meal, thus ending our memorable time in Lalibela. As we said goodbye to our hosts, we looked forward to our flight to the Simien mountains the next day, in anticipation of further adventures.

(To be continued)