Anna Christie at Lyric Stage

Revival of O’Neill’s 1921 Pulitzer Winner

By: Charles Giuliano - May 06, 2018

During a recent visit to Boston we attended one of the final performances of a riveting production of Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie which closed on May 6. In 1921 it was the first of four of his plays to win a Pulitzer Prize. The fourth was the iconic Long Day’s Journey Into Night which was produced and won the award posthumously.

The Lyric Stage production directed and adapted by Scott Edmiston attempted to tighten and contemporize the compelling but cumbersome play. We have four acts abridged into a more manageable two with a running time of some hour each with intermission. Minor characters are jettisoned.

The most significant surviving one of two is Marthy (Nancy E. Carroll) the hard drinking, blousy, live-in barge mate of captain Chris Christopherson (Johnny Lee Davenport). After a couple of rounds of rotgut with the newly arrived Anna Christie (Lindsey McWhorter) she ships out to make room for the long lost daughter of her old salt lover.

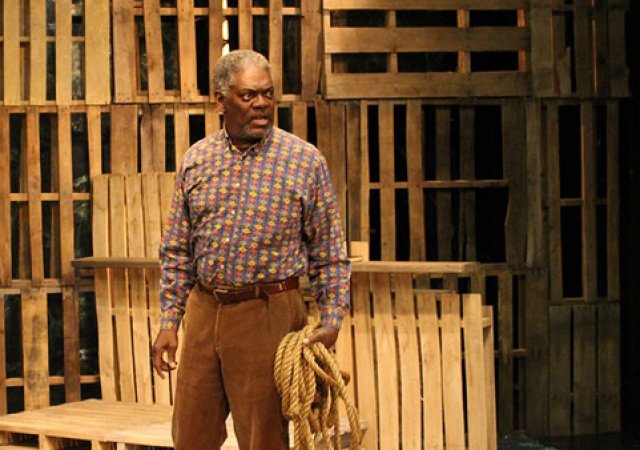

The rough hewn set by Janie E. Howland conflates a bar with the cabin of a barge. The unfinished texture of the wood creates an analogy for the lack of refinement and polish of the splintery characters. At key intervals in the drama, just as in O’Neill’s personal life, these transitions are accented by rounds of knocked back shots.

The pace of the first act, including an awkward reunion of father and daughter, is as slow and creeping as the fog that rolls in. Quite literally the dramatic tension and fulcrum washes up as the identifiably Irish stevedore Mat Burke (Dan Whelton).

This drowned rat cleans up in a cheap, ill fitting suit and slicked back hair as a potential love interest and ensuing suitor for Anna who proves to be less eligible than initially assumed.

By the second act, having established a back story, the production evolves into a three hander and dramatic hurricane. In this triangle the men are protagonists for the rent asunder, torn and tattered, vulnerable Anna.

As is true for much of the massive O’Neill canon the play draws from his horrendous life experience, in this instance, as an often down and out, stranded and abandoned, alcoholic merchant marine. The character of the captain is named for and inspired by one of his former shipmates.

In the hierarchy of the sea, a captain even as lowly as one who skippers a barge, by far outranks one of a gang of roughians who shovel coal to stoke the fires in the bowels of a barge. This lowest of the low is not fit to pursue the hand of his less than pristine daughter.

Another O’Neill drama The Hairy Ape has an uncouth but earthy and sexually menacing, beastly stoker as its central character.

The playwright crafted Christopherson and his daughter as Swedish and it is usual to direct them with an accent. The norm is to play Anna to type as in the famous film version that starred Greta Garbo in her first talking picture. The Norwegian actress, Liv Ullman, the muse of the Swedish filmmaker, Ingmar Bergman, played Anna on Broadway in the 1977 José Quintero revival.

In a notable strategy of color blind casting Anna and her father are played by African American actors. It is entirely plausible and works seamlessly in this production. This director’s decision has given us the always astonishing work of Davenport. This formidable actor is well known to Berkshire audiences for many performances with Shakespeare and Company.

Yet again, his work is so richly voiced, booming and authentic that he tends to dominate and overwhelm the second act. The feisty, rough and proletarian Whelton ups his game in a toe-to-toe, violent confrontation. The audience is swept into this generational struggle which brings out the best of a younger player in conflict with an actor with more life experience and deeper chops to draw upon.

Literally caught in the middle is the finely tuned and compelling McWhorter who is tasked with the nuances of conveying an abandoned woman. Anna has suffered neglect, rape, and two year period as a prostitute. She has sought out her father for reunion, redemption and salvation. Rather than taking charge of her own destiny she is a rag doll being tossed about by the raging machismo of her father and lover. In despair she opts to pack up and move on or back to the death thrall of a horrific past.

That’s a lot to ask of any actress and McWhorer navigates this brutal headwind with understated, angst infused, subtlety and grace. So much so that some reviewers of this production discuss the notion of O’Neill as a proto feminist while, in real life, he was better described as a misogynist.

He brutalized wives drawing them into his cycles of debauchery and alcoholism. Initially, he adored his daughter Oona, typecast as debutante of the year, who was wooed by and married an older man, Charlie Chaplin. He disinherited her. Ironically, she had a happy marriage resulting in a large family he had no contact with. Their daughter, Geraldine, had a career as an actress.

The conflict of tormented biography, and remarkable depth of the oeuvre, is a part of the ongoing critical commentary regarding the greatest American playwright of his generation. It is much to the credit of Lyric Stage that it has taken on a rich but challenging early monument.

It is likely that O’Neill would approve of the changes and casting of this play. Because, or in spite of, his horrific personal life O’Neill’s plays reveal prescient empathy and compassion for women, including tarts and bar-flies, as well as African American characters. Both these elements figure into his epic “Iceman Cometh.”

In Chicago, at the Goodman Theatre, we saw John Douglas Thompson as Joe Mott. That led to a fascinating dialogue with Thompson about black characters in the O’Neill canon. He won an Obie for The Emperor Jones at Irish Repertory Theatre. Joe Mott was inspired by a Bowery buddy who often nursed him through the ravishment of binges. That form of racial bonding was more plausible on the lowest end of the social spectrum. It’s a proletarian stratum that O’Neill mines with authority and authenticity. It’s a part of how these well crafted characters transcend time and continue to ring true.

In 2015, former Long Wharf artistic director, Gordon Edelstein, mounted his fourth production of A Moon for the Misbegotten for the Williamstown Theatre Festival. To keep it fresh and challenging he cast Audra McDonald (Josie Hogan), Howard W. Overshown (Mike Hogan) as the “Irish” Connecticut tenant farmers.

While McDonald brought all of her remarkable earthiness to yet another O’Neill madonna/ puta character critics, including the Times, did not give her or the production benefit of the doubt. For my money it was the best work of the season.

In that regard, the switch from Swedish to African America in the Lyric production was nearly flawless.

When the sordid past of Anna was revealed the initial response of her “deceived” suitor was homicidal rage. Love prevails when the exposed, vulnerable, reformed Anna creeps back into his affection. He will marry her if she will swear on his mother’s rosary that she will be a true and faithful wife.

Anna submits to this test and humiliation. After the fact he asks, by the way, you’re Catholic aren’t you? That evokes spontaneous laughter from the audience. It briefly calls into question the entire premise of the casting. There were similar audience conundrums with A Moon for the Misbegotten.

Consider, however, that this is theater which in order to remain vital demands to be refreshed, deconstructed and revitalized. The Lyric production accomplished that provocatively and magnificently.

By Eugene O'Neill

Adapted and Directed by Scott Edmiston

Scenic Design, Janie E. Howland; Costume Design, Charles Schoonmaker; Lighting Design, Karen Perlow; Composer/Sound Design, Dewey Dellay; Fight Choreographer, Jesse Hinson; Dialect Coach, Amelia Broome; Production Stage Manager, Diane McLean; Assistant Stage Manager, Geena M. Forristall

CAST: Nancy E. Carroll, Johnny Lee Davenport, Lindsey McWhorter, James R. Milord, Dan Whelton

Closed May 6

Lyric Stage Company

140 Clarendon Street, Boston, MA

Box Office 617-585-5678 or www.lyricstage.com

Charles Giuliano is a member of the Executive Committe of American Theatre Critics Association.