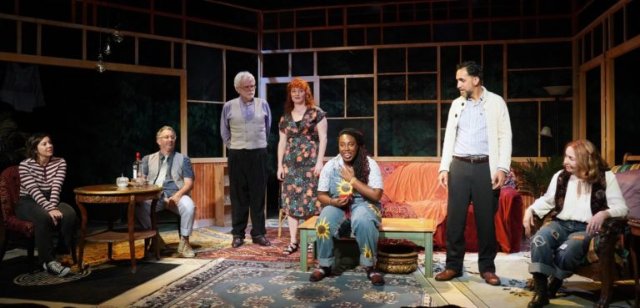

Life Sucks by Aaron Posner

Deconstructing Uncle Vanya for the Umpteenth Time

By: Victor Cordell - May 12, 2019

Adapting classics is a noteworthy undertaking in modern theater. In recent times in the Bay Area, updates of Chekhov have been popular. For a contemporary playwright, it must be nice to have a prefabricated plot and characters and be able to focus on adding modern sensibilities to the proceedings. Stupid F***ing Bird (from The Seagull), Kill the Debbie Downers (from Three Sisters), and Vanya and Masha and Sonia and Spike (a mashup of several Chekhov plays) and perhaps others have appeared here.

One has only to look at the titles of the contemporary plays to sense that these adaptations take source material that is mood-driven, nuanced, and reflective, and turn them into explicit, raucous renditions. Now comes Life Sucks, a modernization of Uncle Vanya from Aaron Posner (who also wrote Stupid F***ing Bird) that hews closely to the plot line of the original but diverges greatly in tone and form.

Life Sucks entertains and has literary and artistic merit. It renders Chekhov less distant and stuffy. The Brian Katz directed staging is well crafted, and the actors portray their characters with great aplomb. The playwright, however employs stage mechanisms that don’t always work well. One device is conversation overlap, which conforms with naturalistic communication. However, the several instances in which it is used are perhaps too naturalistic, because it is not clear that the overlap is with intent, and many audience members will sense, incorrectly, that the actors are flubbing their lines. Breaking the fourth wall is the other device that is heavily employed, and it will be discussed at length below.

Since this work is based on a classic that many theater goers will know, spoiler concerns will be dispensed with, though there are tons of revelations beyond this review. Like its predecessor, the plot of Life Sucks goes virtually nowhere, and in the closing powwow, the philosophical musings revisit the same issues that appeared from the outset. Nothing has changed. Sonia, the young woman who inherited the property where the action takes place, still has unrequited love for Dr. Aster. The Professor, who is Sonia’s previously estranged father and is now married to a young wife, still has no solution to his financial problems. Ella, his alluring wife, still must constantly fend off sexual advances. Vanya, who is Sonia’s uncle and manages the property with her, still resents his suffering from unfulfilled potential. And so on.

Uncle Vanya is a comedy in the sense that it is full of pitiable, laughable characters in awkward situations, and nobody dies (but one almost does!). In Life Sucks, Posner makes the characters more ridiculous and more expressive to add energy and bolder humor. Vanya is shlepier. Aster is more passionate for his causes. Ella is a stronger magnet.

The ultimate question raised is “Does life suck?” But even if it does, what is the alternative, and should we be discouraged from pursuing things that make it better? A related issue that surfaces concerns the notion of the unseen inner-self. We often believe that if others only knew our inner person, we would be better respected and loved. But is there really an inner person, or are we all just the outer person that others are aware of? And do bad decisions derive from the delusion about the putative inner you? The good news is that in their stumbling quest to know the meaning of life, the characters in this drawing room are very well defined and differentiated, and a great deal of humor and thought stimulation is extracted from their despair.

One debatable practice in Life Sucks is its veritable smashing of the fourth wall. Chekhov eschewed stage devices totally, but playwright Posner specifies and allows directors to use this device so extensively that it is integral to the play’s style and substance. Accordingly, comments are in order. Several thematic variations of speaking directly to the audience are used, and following is a subjective ordering of their effectiveness.

1 A few minutes into the play, Sonia details who the characters are and their relationships – This works extremely well in reducing confusion, so that the audience doesn’t miss things because they are trying to figure out who’s who.

2 At the outset of the play, Sonia announces that it is about love, longing, and loss – Though this disclosure reduces the audience’s sense of discovery somewhat, it makes it easier to identify these aspects of the narrative and evaluate the play in terms of its objectives.

3 Intimate soliloquies by each character – They help in elaborating the characters and understanding their motivations better.

4 End of act notifications – brief, cute, innocuous.

5 The cast’s detailing things that make them happy and sad – This burns time. We get, for instance, that all manner of things can make us happy, from cheap ice cream to “being right”, without listening to laundry lists of them.

6 Interaction with audience asking their experience and opinions – This device distracts and creates clumsiness, unevenness.

In sum, Life Sucks is an enjoyable and provocative evening at the theater, but in making it more hip, focus is sacrificed without enrichment.

Life Sucks by Aaron Posner is produced by Custom Made Theatre and plays on their stage at 533 Sutter St., San Francisco, CA through June 1, 2019.

Posted courtesy of For All Events.