Refus Global to Intersectionality

Rethinking Paradigms for Canadian Art

By: Charles Giuliano - May 14, 2019

Le Refus global, or Total Refusal, was an anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto released on August 9, 1948 in Montreal. Of the 400 printed copies only half were sold. But the impact was profound. It stated in part:

Make way for magic! Make way for objective enigmas! Make way for love! Make way for what is needed!

We accept full responsibility for the consequences of our total refusal.

Self-interested plans are nothing but the stillborn children of their parents.

Passionate actions have a life of their own.

We are happy to take full responsibility for tomorrow. Rational effort can only release the present from the constraints of the past when it stops looking back.

Our passions will spontaneously, unpredictably, necessarily forge the future.

Although we must acknowledge the past as the birthplace of the future, it is far from sacred. We owe it nothing.

Signed by: Magdeleine Arbour, Marcel Barbeau, Bruno Cormier, Claude Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Muriel Guilbault, Marcelle Ferron-Hamelin, Fernand Leduc, Thérèse Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Maurice Perron, Louise Renaud, Françoise Riopelle, Jean Paul Riopelle, Françoise Sullivan.

With some irony works by leaders of anti-establishment and anti-clerical radical artists of the post war era now have pride of place in permanent collection galleries of major Canadian museums.

To some extent they conflate with The Irascibles a group of eighteen New York artists who signed a letter to the president of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, rejecting the museum's exhibition American Painting Today - 1950 and boycotting the accompanying competition. The subsequent media coverage of the protest and group photograph, that appeared in Life magazine, gave them notoriety. The artists comprised the core of Abstract Expressionism.

Artists signing the letter were the painters Jimmy Ernst, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Hans Hofmann, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Richard Pousette-Dart, Theodoros Stamos, Ad Reinhardt, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Willem de Kooning, Hedda Sterne, James Brooks, Weldon Kees and Fritz Bultman. The supporting sculptors were Herbert Ferber, David Smith, Ibram Lassaw, Mary Callery, Day Schnabel, Seymour Lipton, Peter Grippe, Theodore Roszak, David Hare and Louise Bourgeois.

A commonality was the influence of automatic surrealism particularly the experimental applications of pigment by Max Ernst and abstracted dream forms of Roberto Matta. Following the devastation of Europe, and demoralization of the School of Paris, the matrix of the avant-garde shifted to New York. One may argue that there was an aftershock in Montreal.

Recovering from global war there was hope of a new order through a confluence of creativity and psychoanalysis mediated by aspects of automatic painting. For artists like Jackson Pollock the act of painting was conjured as a frenzied séance and dance macabre.

This time of radical change in art was the focus of the summer long exhibitions, seminars, and debates of Forum 49 in the artist’s colony of Provincetown. Two relatively obscure signatories of the Irascibles were key participants in the Provincetown events; Weldon Kees and Fritz Bultman. The latter artist had studied with Hans Hoffman in Germany and helped his wife emigrate to the U.S. In Provincetown Hoffman established a school with many students participating through support of the G.I. Bill.

Art historians have documented the ascendancy of the New York School. Consider the Marxist book by Serge Guilbault “How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art” or the studio inflected Vasari-like “Triumph of American Art” by Irving Sandler.

There is the familiar process through which the art of protest and rebellion, the now superannuated notion of an avant-garde, trips over its self-righteous rage morphing into the mainstream. Works by artists living in cold water flats and lofts, selling when and if for a few hundred dollars, are now worth umpteen millions.

Back in the day artists fought, argued and cried in their beer at the Cedar Tavern. Now dealers in their estates laugh all the way to the bank. Visitors to museums, particularly younger ones, have little or no sense of the outrage and agita, privation, alcoholism and sexism that pervaded, motivated and deranged the great generation of American, and yes, Canadian post war artists.

While celebrating its own artists American museums, curators, critics and collectors, for the most part, have ignored and neglected the equally compelling, seminal works of our Canadian friends and neighbors. That benign status quo continues today as few if any contemporary Canadian artists are selected for the vast global network of biennials.

Even Canada’s own biennials, most prominently curator Claude Gosselin’s Les Cent jours d'art contemporain de Montréal have been abandoned. There were a few such attempts by The National Gallery in Ottowa. It is difficult to sing along when the Canadian art establishment declines to toot its own horn. There was a time when there was strong government support but now less so. In the arts, as with everything else, one has to spend money to make money.

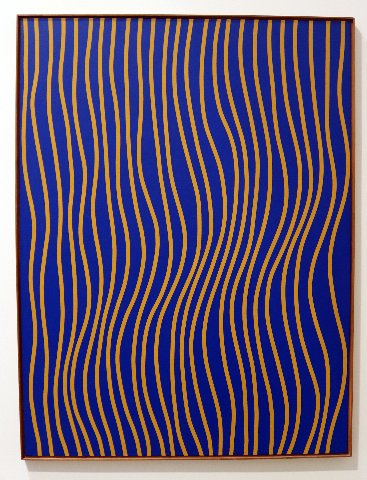

In addition to Canada’s great generation of Refus Global there was another group of abstract/ formalist artists that was prominent in the 1960s. Guido Molinari and Claude Toussignant participated in MoMA curator William C. Seitz’s 1965 exhibition “The Responsive Eye.” Based on that exposure they were represented by the East Hampton Gallery of Bruno Palmer Poroner. He also showed Marcel Barbeau, who signed Refus Global, and Jacques Hurtubise. I worked for the gallery and knew Barbeau who lived in New York and met the others when they drove from Montreal to deliver new work.

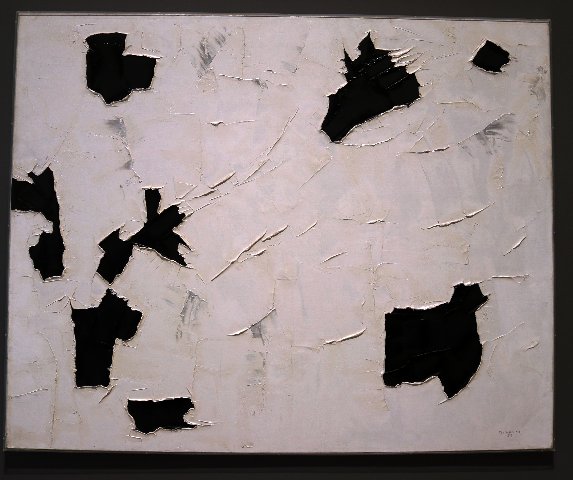

During our recent two week tour of Montreal, Ottowa, and Toronto it was insightful to catch up with old friends. Encounters with works by Borduas and Riopelle confirmed earlier notions that their work was on a par with the best American artists of their generation. In particular, the museums focus on the late works of Borduas when he limited the impasto rich surfaces to creamy swaths of white and black. They draw comfortable comparisons to black and white, abstract expressionist canvases by Franz Kline.

There were encounters with monumental, staccato pallete knife, paintings by Riopelle. From post impressionism and pointillism he derived a visual vocabulary of richly mottled color accents. There is equivalence to the “all over paintings” as defined by Clement Greenberg and represented be the flung skeins of paint by Pollock. Works by Riopelle evoke the American Joan Mitchell. They met in Paris in 1955 and separated in 1979. There is similarity of intensity and touch. They are both artists deserving of far more mainstream recognition.

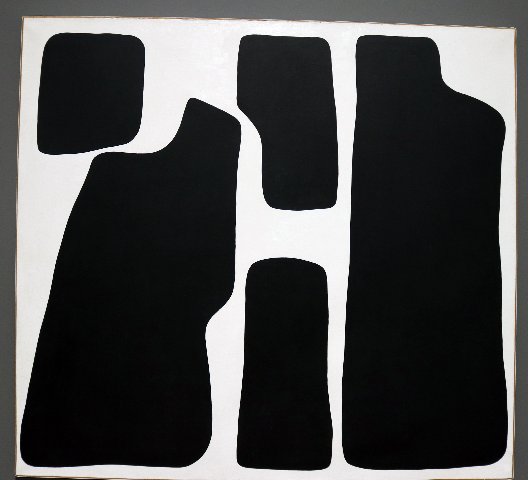

From their New York exhibitions in the 1960s I knew Molinari for vertical stripe paintings and Toussignant for his targets. During our museum tour it was wonderful to see examples of earlier work. In the case of Molinari skillful, thick impasto that reflect what Borduas was doing. There is now a Molinari Foundation with the mandate to support younger artists and keep his name and work visible at least in Canada.

Works in the museums also inspired me to upgrade evaluation of Barbeau. There was far more range to the oeuvre that I knew from New York.

The ebb and flow of alumni of The Responsive Eye follows with the overall critical evaluation of Op Art. There were other stripe painters like the Washington Color Field artist Gene Davis and other Op target painters. In the current mélange or mainstream critical thinking there is tepid interest in aspects of formalism.

There are other Canadian artists we would enjoyed seeing more of. It was disappointing not to see work by the always interesting Françoise Sullivan. We saw some but not enough of the Color Field painter Jack Bush. There were tantalizing glimpses of the diverse, eclectic work of the ninety-year-old Michael Snow. He was included in the uneven MASS MoCA survey Oh Canada a few years ago. Snow was one of the few established artists in that project.

The major Montreal artist, Betty Goodwin, was confined to a corridor of works on paper in the Art Gallery of Ontario. She was underrepresented as one longed to see a major figurative painting or example from her signature series of draped felt or quirky magnet pieces. Similarly, we found only a single piece by the important, Montreal-based artist Geneviève Cadieux.

With just rare examples on display Canadian curators seem unclear how to represent Agnes Martin and Philip Guston. The Canadian-born artists had major careers in the United States.

In the decade since our last visit to Canadian galleries and museums there has been a major shift in national consciousness and curatorial strategies. There is a revisionist agenda to rethink cultural history exploring intersectionality and social justice. That means an adjusted narrative focused on contributions of First Nations artists.

For the moment, that has resulted in awkward installations. Historically there was no confluence between high art and folk traditions now, by fiat, they are woven together. In the midst of displays of abstract painting are vitrines of Inuit sculptures or walls of Arctic-inspired, narrative prints and drawings. Sharing commonality as Canadians, visually, the artists are apples and oranges.

Moving forward through education and cultural development the disparity between First Nation and mainstream Canadian artists will be less demarcated. Inclusion will influence and morph the art with a potential for more sophisticated techniques and expressions. For now concerns are most evident in limitations of material. Sculpture is executed in stone and bone while two dimensional work primarily consists of drawings limited to pencil, pastel, crayon and markers.

Much anticipated potential development is richly evident in contemporary African American art. One recalls the protest, burn baby burn, agit-prop of the Civil Rights era. A generation later artists of color comprise a rightful and righteous position in the global mainstream. There is a lively secondary market of historical 20 century African American artists. In 2018, for example, there was a major MoMA retrospective for the figurative/narrative artist Charles White. That wouldn’t have happened even a decade ago.

There is diminished need for affirmative action in American art and culture. No doubt one day that will be true for Canada. Until then its a bit fubar.

While we sing the anthem “Oh Canada” let’s chime in with a refrain of “The Times They Are a Changing.”