Ethiopia: Part Two

Simien Mountains, Gondar, Bahir Dar

By: Zeren Earls - May 15, 2020

On the way to the Lalibela airport to get to the Simien Mountains, we stopped by the humble home of a woman who is an ex-officer in the Ethiopian military. We heard her story of fighting against communists during the Ethiopian Civil War, when both her husband and baby were killed deliberately and she was driven out of town. Years later she decided to return to her home town and begin life anew. In her modest living room, while I listened to her story with a heavy heart, my eyes were fixated on a big plastic water jug – often a sign of no running water. In fact, outdoors not far from her house, a young woman was washing her hair with water out of a jug as well, while a little distance away men hauled wood on their shoulders to a construction site. For all these people built-in resilience came with the turf.

A 30-minute flight to Gondar, followed by a drive of about three hours, brought us to the Simien Lodge, our home in the mountains for the next two nights. A sign at the gate claimed it to be the highest lodge in Africa, at 10,700 ft. We each settled into our own small, round hut with thatched roof. Before dinner we were treated to a documentary in the lounge on geladas, a type of monkey found only in the Ethiopian Highlands. Adorned with long, bushy hair, they spend the night on the cliffs to avoid predators and come down to flat ground to feed during the day. Having learned about these unusual-looking monkeys, I went to bed with great anticipation.

Our morning drive to Simien National Park, followed by a nature walk, introduced us to the scenic splendor and wildlife that has earned the Simien Mountain range, known as the “Roof of Africa,” a UNESCO World Heritage Site designation. Massive erosion over millions of years on the Ethiopian plateau has left behind majestic mountains with deep ravines, sharp precipices and jagged peaks rising up to 15,000 feet. Accompanied by park rangers during our walk, we met young boys selling hand-crafted woolen hats, who later broke into a dance to entertain us. Two danced while the others sang and clapped.

Endemic species of wildlife find sanctuary in the Simien Mountains. We had the good fortune to come upon a field of gelada monkeys who had descended from the mountains for their daily meal. The spectacle included monkeys of different generations, digging into the grassy field with their hands to get to the moist roots of the plants. They also socialized by picking fleas off each other, especially their babies.

On the way back to the lodge, we stopped at a scenic area to enjoy our boxed picnic lunch. Just as I settled on a rock, a big black crow hoping to get food scraps landed on another rock nearby. Not to disappoint it, I threw it some bread. This African crow had a thickset body, glossy plumage, long pointed wings and a short, stout bill. Not to miss out on the food, another crow landed right behind the first one. Then, as luck would have it, two antelopes emerged from behind the hill, looking at us, but frozen still – a perfect picture framed by the trees. Then it was time to leave for a restful afternoon at the lodge amidst the dramatic mountain scenery.

The next day we traveled overland to Gondar, a two-hour drive from Simien National Park. Our adventures started in the daily market, a colorful, bustling spread with animals and people, like others we had seen, except this one had an area for male tailors busy at their sewing machines, while women occupied a corner for sifting grains. In fact, later on by the roadside we saw farmers with horses and cows thrashing grain.

Our lunch stop was at the Four Sisters Restaurant, where we learned how to make tej, a wine made by mixing raw honey in hot water and boiled with an indigenous herb like hops. An orange-colored drink often made in people’s homes, it is served in small glasses and sipped slowly, as the alcohol content is quite high. While we enjoyed our drinks, we were entertained by a musician who played his masingo, a one-string fiddle we had seen at the Ethnological Museum in Addis.

Gondar is a fortress city along the Angereb River, rising from the foothills of the Simien Mountains. Founded in 1632 by Emperor Fasilides of Ethiopia’s Solomon Dynasty, it was the seat of royal power for 200 years. During this time, a succession of kings built stone palaces, churches, monasteries and forts. A 2700-foot-long wall extended around the structures, known as Fasil Ghebbi, the “Royal Enclosure.” We spent the afternoon at Fasil Ghebbi, recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, walking around the various palaces. Regrettably, we could only imagine how they might have been furnished, as all the contents have been stolen during the civil war.

In the same royal complex, Emperor Fasilides’ Bath, a large pool surrounded by a stone wall with six turrets, stands empty, except during the three-day Timket festival, a celebration of the Ethiopian Epiphany, marking the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. During Timket the pool is decorated with small flags in the colors of the national flag – yellow, green and red – and attracts a large number of pilgrims, who take part in the festival and witness a re-enactment of the baptism.

Visiting a local school was yet another window into life in Ethiopia. Although schooling is mandatory, the rule is not enforced. Families have seven-to-ten children on average. Many parents keep children at home, as they are a source of extra labor for herding animals, fetching water and the like. We visited several classes, where children learned English in addition to Amharic. Their faces lit up as they received gifts from us. A few kindergarteners danced for us; older boys played soccer during recess with a new ball received as a gift.

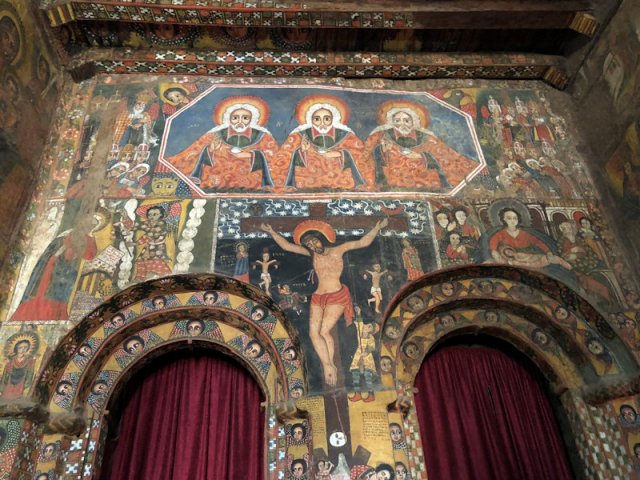

On the way to the Debre Birhan Selassie Church and Monastery in Gondar, we stopped to visit with the seminarians, who live in small huts next door. Debre Birhan is a small stone church with an interior completely painted with Ethiopian Christian art. The entire ceiling is covered by the faces of angels. When you look up there are rows of angels looking down at you, regardless of your viewing angle. Biblical scenes, first painted on canvas in richly applied red, blue, and golden hues, have been pasted onto the walls. The Holy Trinity seated above Christ on the Cross is the centerpiece of the biblical stories. The church also has musical instruments, such as drums, played during special occasions. The priest showed us the drums, but could not demonstrate, as our visit coincided with Lent.

Following a brief rest, we set out for further discoveries, first to a Falasha village, then to a craft center. The village is home to a small group of Falasha – Ethiopian Jews. “Falasha” is a derogatory name, meaning “stranger” or “exile,” given to Jews by the Amhara, who conquered them in 1616, killing, enslaving or converting them. Until recently the Falasha had no education or land rights. Although some were relocated to Israel, many returned because they were shunned there as black Jews. Falasha constitute 1% of the Ethiopian population; most of them live in Gondar province. Our visit was a walk about the grounds, which included dwellings, a synagogue and a corner for souvenirs, where I purchased a tiny black clay box with the Star of David on the outside and tiny clay figures of King Solomon and Queen Sheba under covers inside, heralding the beginning of Ethiopia’s Solomon Dynasty.

The craft center is a place for single mothers and HIV-positive women. They live here to learn various skills, such as pottery, weaving and dying various grasses to weave baskets. Otherwise they are often on the streets begging. There is no birth control in Ethiopia. Very young girls are often seduced into having sex with older men, ending up pregnant or crippled, which then leads to rejection by their families. Pre-marital sex is not accepted in conservative Ethiopian society. During our walking tour later on, I saw a blind woman with a baby on her back, trying to make her way along the sidewalk with her cane – a heart-wrenching site. Returning to the Gondar Hills Resort House to enjoy a view of the city from afar out of the large picture window of my lodge provided the calm I needed before packing up to leave for Bahir Dar the next morning.

Bahir Dar (which means “By the Sea” in Amharic) is a four-hour drive south of Gondar, at an altitude of 6000 feet, which is low by Ethiopian standards. It is a tropical town by Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile. Soon after we crossed the river, palm-lined streets emerged on the way to the Kuriftu Resort and Spa. The resort, set within a large garden with a swimming pool, seemed the perfect spot to spend the final two nights of our adventurous trip.

Following a delicious lunch of grilled perch with garlic-lemon sauce in the lodge restaurant and a rest, we assembled in twos for a tuk-tuk ride into town. Wide streets with cars, a contemporary church across from a newly-built mosque and pedestrians in western-style clothing signaled that we were at the prosperous end of the lakeside town. We were dropped off at the local open-air market, where many of the craftsmen seemed to specialize in goatskin furnishings, ranging from ottomans to table covers. Vendors dressed in bright African print fabrics sat behind heaps of produce, grains, spices and everything else imaginable.

The next day’s treat was a boat ride on Lake Tana. We boarded a boat from the dock of our resort to visit two of the many ancient monastic churches that dot the 20-plus islands. Our boat was “protected” by a large angel, painted right behind the captain’s wheel. On the way we saw beautifully crafted papyrus boats, hippos submerging and emerging from the water, baby alligators resting on rocks along the water’s edge, and endemic birds on trees as we approached the islands.

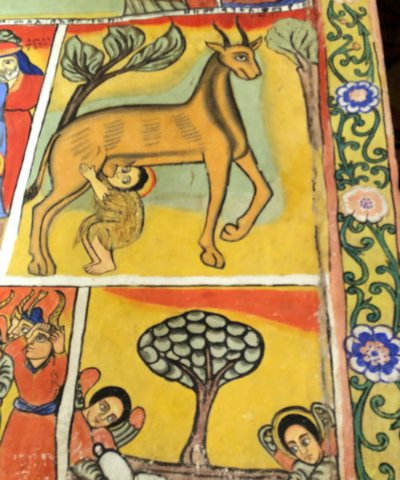

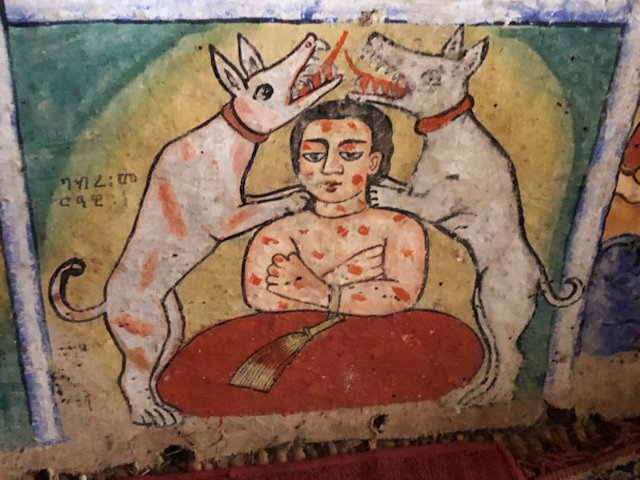

Once we landed, we had to hike uphill for about half an hour to get to the monasteries. The path was lined with souvenir stalls, making it difficult to avoid eyes pleading us to buy. Our first stop was at Ura Kidane Mehret, a 14th-century monastery, circular on the outside and with a six-sided chapel inside. All the interior walls are covered with frescoes depicting biblical scenes and the history of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. While some of the images are whimsical, others are quite cruel, such as ones depicting horses trampling over non-Christians and making blood squirt from their heads. An image of the Virgin Mary with the Christ child can be seen through a tulle veil, which is lifted during worship.

The second monastery we visited was Azwa Mariam. Outside in the yard, a very large rock suspended from chains like a swing acts as a church bell when hit by a smaller rock. The monastery is a circular building, with interior clay walls painted from top to bottom depicting Ethiopian Orthodox liturgical scenes. Despite the distance one has to travel to get to these monasteries, many seek them out to pray, chant and worship. Glad to have seen these ancient sites, we took the boat back to the Kuriftu Resort.

Driving out to see where the Blue Nile joins Lake Tana was to be the final treat of our trip. However, there was a sand storm brewing over the river when we got there. What started as a sand-colored view turned into a major sand storm, causing all air traffic to shut down at Bahir-Dar airport. Our flight to Addis the next day was cancelled, requiring us to make the journey overland. In order to get to Addis in time for our flight home, we left Bahir Dar very early in the morning and endured a twelve-hour trip over mountainous roads. My parting photo was of a monkey on a rock by the roadside, keenly watching traffic go by.

A week after we returned to the US, Ethiopia’s land and air borders were regrettably closed; as of this writing, there are many confirmed cases of COVID-19. Self-quarantining is a luxury few can afford. Crowded markets, informal settlements, often without running water, and a way of life that depends on day-to-day personal transactions offer no protection against a disaster such as a novel virus. Limited healthcare services, the difficulty of social distancing in packed communities and the absence of economic safety nets are incubating a tragedy that will be very difficult to overcome.

Ethiopia is a country already in the midst of tremendous change with the end of the Eritrean border war. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, recently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, is leading this change. May he have the vision and fortitude, as well as the means, to lift his people out of the human tragedy of COVID-19.