The Power Plant

Toronto’s Renowned Contemporary Art Kunsthalle

By: Charles Giuliano - May 16, 2019

In 1976, Harbourfront Centre in Toronto established the Art Gallery at Harbourfront. Utilizing reuse architecture The Power Plant was officially opened in 1987 in its current location. A primary destination for contemporary Canadian and global art it has functioned as a kunstahalle or non collecting organization.

Admission is free but it cost us $25 for public parking. Much has changed for the waterfront of Toronto since our visit some years ago. A former sense of natural surroundings has morphed into a dense impact of glass and steel condominium and office towers. The museum itself remains the same but, through a glitch, we almost made a fruitless visit.

Our first challenge was finding a non-franchised restaurant within walking distance. We lucked out in discovering a small Indian restaurant.

The sign on the door to the museum, however, indicated that it was closed on Wednesday’s the day of our visit. It was a lovely, bright, sunny spring day so we opted to hang out along the waterfront. We considered a 45-minute harbor cruise but the boat was out of commission.

Plan B entailed strolling about eventually ending on the terrace of a restaurant for a cuppah. We soaked up the sun and lakeside ambiance. Prop commuter planes were regularly taking off from a nearby airport.

Astrid noticed that there were people in the lobby of The Power Plant which shares space with theatre facilities. We checked it out and were quite surprised to be admitted. Commenting to staff that the door indicated that the museum was closed there was a surprising response. It seems that door only functions during the summer season. Why, we rightly wondered, not post a note of that schedule?

We were fortunate to catch the last days of three solo exhibitions. When they ended the complex would close for an extended period during annual benefit activities.

The synergy of the three artists comprised diversity, intersectionality, identity and otherness. The work was off the grid of the mainstream Eurocentric art world. The curatorial selection reflected the globalization of international art fairs and biennials.

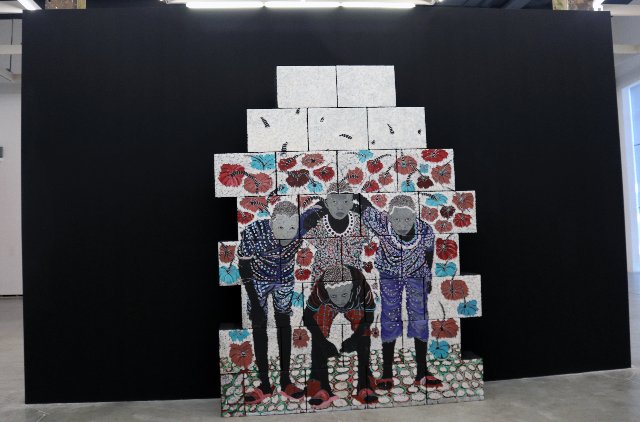

The program included “Same Dream” by Omar Ba a Senegalese artist who divides time between Dakar and Geneva, Switzland. Shuvinai Ashoona, a member of a renowned family of Inuit artists, presented “Mapping Worlds.” For twenty years, Alicia Henry, a graduate of Yale, has resided in Nashville, Tennessee where she teaches at Fisk University. Her show was titled "Witnessing."

While Ba and Henry were having their first solo, Canadian museum shows. All three artists have exhibited internationally. We recall the work of Shuvinai Ashoona for its inclusion in the 2012 MASS MoCA exhibition “Oh Canada.” It curator, Denise Markonish, made some 400 studio visits including by snowmobile.

Critical response, however, was tepid. As Karen Rosenberg reported for the New York Times, “ “Oh, Canada,” a 62-artist affair that sprawls over most of Mass MoCA’s first floor, wants to be that kind of national-scale megashow. But in trying, it becomes something much quirkier. Seesawing between bigness and intimacy, the personal and the communal, it may tell you more about Canada’s identity crisis than it does about Canadian art.”

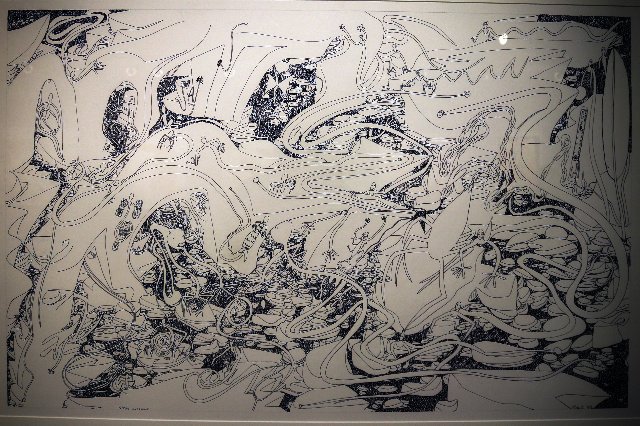

Given that “quirky” off kilter overview from the perspective of a single curator, with no prior knowledge of Canadian art, it was informative to revisit a broad, representative range of works by Ashoona. It gave an enhanced sense of her skill set and mastery of intricately detailed drawings as well as immersion in culturally specific, complex narratives.

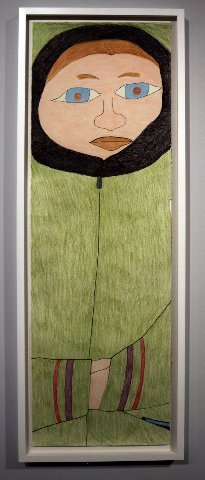

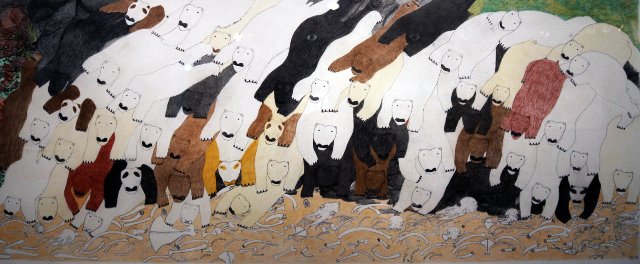

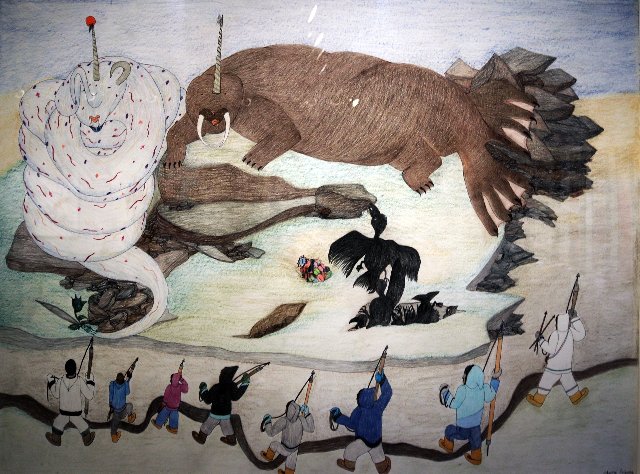

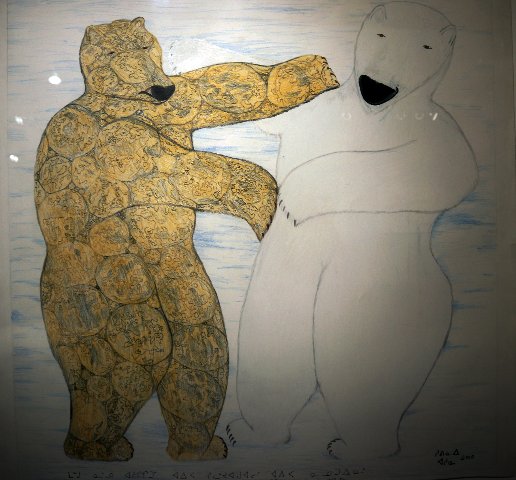

There are views of communal hunting and fishing as well as elaborate surreal fantasy images of gods, monsters, and mother nature. One wall entails vertical, narrow, compressed in the frame caricature/ portraits. We were particularly amused by a rendering of a polar bear dancing with a large brown bear. Often the iconography is intriguing but remote for a general viewer not schooled in her culture's myths and legends.

With wonderful serendipity there are shared sensibilities with similarly unique and emotionally charged works of Ba. One senses commonality that curators were striving for. The artists represent different paradigms from the isolated, insular Arctic to the charged and chaotic, urban Senegal The latter we experienced first hand several years ago. Again one could sense a palpable, West African pulse and energy in his work.

Arguably, there are issues of cultural identity in the work of Henry but imagery that comprises abstracted silhouettes and narrative is implied rather than specific. This difference is more pronounced when compared to the dream/ surreal, complex iconography of the other two artists.

There is a paradox encountering the elaborate drawings of Ashoona. The imagery and intensity of story telling is highly evolved. The techniques of drawing, however, are intricate but technically simplistic. They entail flat, linear renderings that have been enhanced with color pencil and oil sticks. The figuration falls within defenitions of folk and outsider art. There is no sense of depth, dimension, or illusions of forms through chiaroscuro.

That may be a moot point as the work is structured within indigenous traditions. One is encouraged to evaluate the work within its unfamiliar genre rather than a formalist critique of what it is not.

On its own terms, the work is fascinating, evocative and well worth careful consideration. She takes us deeply into the realm of First Nations people. These may prove to be documents of a culture and environment deeply threatened by global warming. We have seen too many images of emaciated polar bears and wild life struggling to survive above the Arctic circle. There is an endgame for sustainability of her way of life and its economic/ social issues.

For unique qualities the artist has been widely recognized. Her father Kiugak Ashoona was a sculptor, her mother Sorosilooto Ashoona was a graphic-artist and her grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona was one of the most acclaimed Inuit artists of her generation. She is also related to artists Napachie Pootoogook, her aunt, and Annie Pootoogook, her cousin.

Among other credits Shuvinai recently worked with the Saskatchewan-based artist, John Noestheden, on a "sky-mural." It was exhibited at the 2008 Basel Art Fair and Toronto’s 2008 "Nuit Blanche". It later traveled to the 18th Biennale of Sydney in 2012 and in 2013 it was part of "Sakahans" an exhibition of international indigenous art at the National Gallery of Canada.

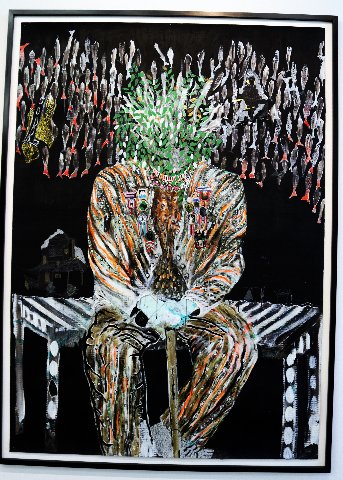

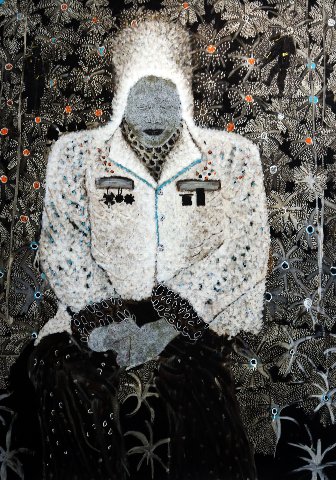

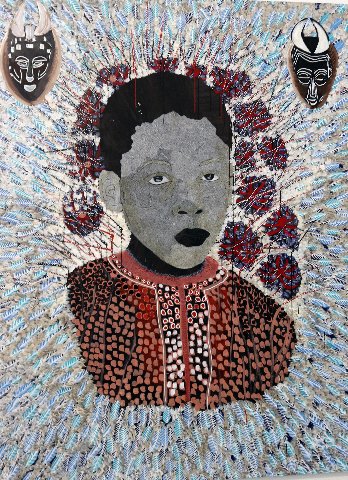

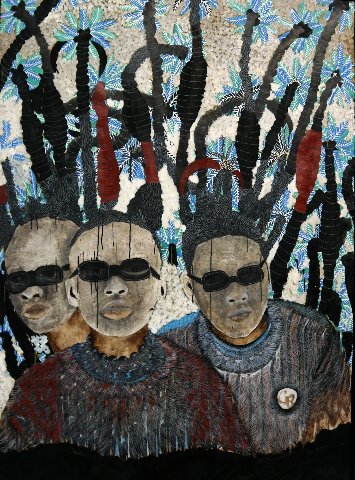

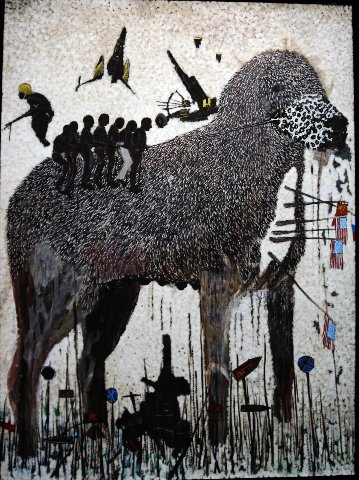

Our first encounter with work by Omar Ba, (Born 1977 in Senegal) was uniquely powerful and astonishing. He is at the forefront of globally recognized African artists. The success of the work derives from its sophistication. He conflates indigenous themes and imagery with suitable scale and punch. The work holds its own and otherness among the usual suspects of international art fairs and biennials. It is no coincidence that he divides time between Dakar and Geneva. That creates synergy between African roots and identity as well as market exposure in the European/ global art mainstream. His work has been exhibited and collected by major public and private institutions including the Fondation Louis Vuitton (Paris) and the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

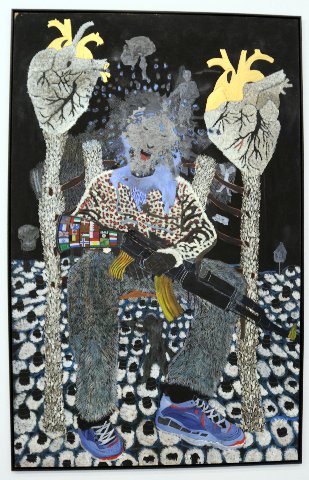

One long wall displayed variations on the theme of enthroned dictators. The series evokes Eugene O’Neill’s “The Emperor Jones.” It recalls an image of Afrocentric power in a vintage Black Panthers poster. In the variations by Ba the dictators have anthropomorphic identities and are embedded in lush, tropical, jungles.

Lest we miss post colonialism and meddling in African politics he makes a neat point. Resting on the lap of one of his para-military strong men is a Kalashnikov assault rifle. On the handle is a grid of decals with flags of several nations including the United States, Great Britain, Israel and Canada. In this context United Nations really means everyone exploiting Africa.

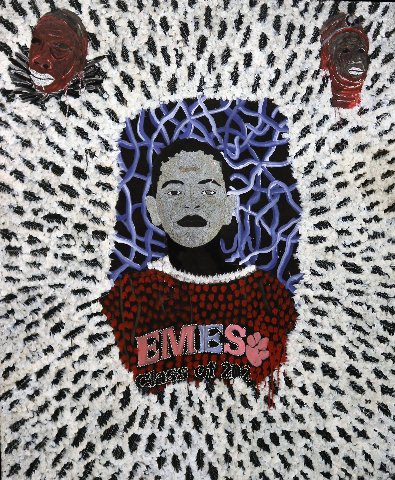

Given the overwhelming richness of the narratives of the other two artists there is a sense of cooling off when navigating galleries displaying silhouettes by Henry. The content and context is implied and the viewer needs to be more proactive.

There were walls with dense installations clustering elements of varying scale and configuration. One series entailed sketchy, fragmentary references to abstracted African masks. Other set pieces featured female, full-figure, frontal nudes. These are interspersed with snippets of body parts and here and there what I interpreted as small heads representing the ancient Egyptian god, Anubis, the jackal.

With so many disparate elements in the work of Henry the whole was less than the sum of its parts. It was never clear just what the artist is striving for. The work considers gender and identity. Ok, now what?

This evocative and challenging mix of exhibitions underscored the programming strength of The Power Plant.