The Sweetest Embrace: Return to Afghanistan

Second Film: Herders’ Calling

By: Astrid Hiemer - May 21, 2013

OXUSfilms:Herders' Calling, 2004 andThe Sweetest Embrace: Returning to Afghanistan, 2008by director Najeeb Mirza

www.oxusfilms.com

Najeeb Mirza has been drawn to film in the countries of Central Asia for more than a decade now. While traveling he first photographed, then filmed there over time and with a small crew hundreds of hours - people and stories in awe inspiring landscapes. By his own admission he still has stories ‘in the can’ or more appropriately digitally saved.

We wrote about his newest film Buzkashi!, 2012, this April and recently viewed two of his other films: Herders’ Calling, 2004, and The Sweetest Embrace: Return to Afghanistan, 2008. Afghanistan is etched in the American psyche mostly in war and political terms, because of the current and long drawnout war. Here, Mirza’s film follows a winding and seemingly far fetched story of two young boys, Amir and Soorgul, who are now men on their return to their homeland and families.

They were plucked from their villages in Northeastern Afghanistan among a large group of Afghani boys during the Russian occupation and war, sent to Tajikistan to be educated and return in later years to become eventual leaders. When the Soviet Union collapsed most of the boys were sent back, yet our two protagonists languished as is conveyed in the film. Finally they emigrated to Canada as refugees with the assistance of an Aids Organization.

Of course, Amir and Soorgul yearned to go home! This is the story of their journey:

They arrived at Kabul Airport among the buzz of a city. We see them at a large open air market purchasing a suit for Soorgul’s engagement party? Then, the men are traveling in a van with a few other passengers north. Occasionally a map is inserted into the film to show their route. Amir’s village, Eshakashem, will eventually be reached first. Several days later, Soorgul walks into his village, Gharan, with a group of people from the area, his belongings strapped to a donkey. News that he is returning has already reached his village.

Oh, what a journey! Progress is made slowly while driving in the mountains on nearly bald tires and on endlessly rocky roads. The first van has a flat tire, which cannot be replaced. None is available! One waits around - the sense of time is timelessness! Someone will come by or someone is sent to the next village for assistance. A second van gets hired to continue the drive.

During one of the conversations in the van Soorgul assures a passenger that while living in other countries he has not forgotten his religion, Allah is still in his heart. He is also one of the English speaking persons, to further the story-line. Subtitles are being used during Afghani conversations and Amir also speaks Farsi. However, he appears not to speak English, even though he has lived in Canada for several years.

We are reminded of the ongoing war, when the van gets stopped high in the mountains by soldiers and searched. There have been bombings in Kabul and the military is on alert everywhere. Soorgul remarked that they were never searched before and here, along an isolated road, they had to download everything. In another scene, a man approaches very cautiously with his donkey, because he thought that the camera man’s tripod could be a rocket launcher!

We also learn that Bobby, an international aids worker, is telling our protagonists that to continue the trip at that point is too dangerous. Of course, they trek on! And Daler, another aids worker is singing hauntingly during a circle of reflection.

They reach Eshakashem and Amir wants to stay for a few days with his family and the two Canadian-Afghani part. First, there is his uncle, who promises to tell him later, where to find his parents. He actually sends him off to Pakistan. The border is not far, but difficult to reach. He learns that his father had to flee from his enemies in the area and so the family left. Amir crosses the river, which is the border at that point, with the help of strangers and spent a month on the Pakistani side, walking from place to place in search of his parents. He so longs to embrace them and to bring them at least a glass of water!

Unsuccessfully, Amir returns to Afghanistan and finds the village of his grandfather. The faces of the people, of older men and women are magnificently marked by time. His grand father tells him the truth: His father died soon after Amir left, his mother remarried and also died a few years later. We see Amir at his mother’s resting site, kissing her grave stone. His most cherished wish was not fulfilled, yet he had returned to his homeland and family – but not to stay.

Meanwhile, Soorgul, a tall and good looking young man, is walking from the mountains down to his parent’s village in the valley, when an older man approaches. Immediately he recognizes his father and the two fall into a long and tearful embrace. Next, there are his mother’s loving open arms, then he meets his younger siblings. Celebrations ensue.

We witness his engagement party to a young woman from the village. Even though he had learned along the way, that the girl he was engaged to as a boy still wanted to marry him, it did not come to pass. His father had brokered the new engagement and the young people appeared content sitting side by side.

Now, will Soorgul stay in the village? The father speaks beautifully in philosophical terms that it would be the son’s decision and the son decides to return to Canada, from where he could more easily support his parents and family financially.

Life in the village is simple and hard. We see both protagonists in Calgary, back in Canada, surrounded by technology and our contemporary trappings. Amir proudly proclaims, in English no less, that he is engaged to be married in three months. And Soorgul conveys finally that he has reached a sense of belonging ’beyond borders.’

Mirza tells lovingly a human story, a story that is repeated globally in war-torn countries with different circumstances or when huge natural disasters hit – often not with a Happy Ending.

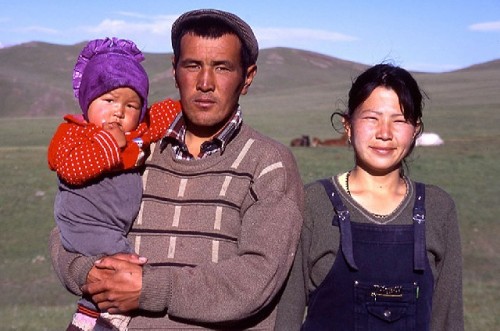

Herders’ Calling is Mirza’s second movie, premiered in 2004. This shorter film brings the viewer to one of the vast valleys of the Kyrgyz Republic, to a jailoo, which are the high pasture lands. There, Nazgul, a young modern woman, milks cows and raises her very small daughter. Her husband’s family has herded sheeps here for centuries. They live in a large, round structure during the summers with his parents; the winters are too harsh.

Nazgul is content for the next few years, but she has plans to grow the herd, sell the animals and move to the city, where she was raised. She does not want her daughter to lead this hard life. Nazgul has a Middle School education and studied Fashion Design. She can sew, design clothes and has a lovely voice. We hear her singing during a celebration, when neighbors from far away have come to visit. Very far away! Long shots show vistas devoid of any neighbors. The tradition of herding on the jailoo is dying out.

Age old customs are important to maintain. So when the visitors arrive, celebrations abound, such as a feast for all by offering flat breads, their own butter and milk products, dishes of meats, watermelon and more.

Other get-togethers include a game of Buzkashi, here played by another name. We watch the small white sheep being killed with bound feet. Later the young men on their horses try to snatch the headless sheep away from each other, while racing across the countryside, until the winner pegs it in the goal. (If you have not read my film review of Buzkashi!, now is the time; it is a fascinating movie!)

Nazgul’s father-in-law, Akim Aliev Datka, retired at 60 from his position in the city and returned to the valley with his family to maintain traditions and live on the land. He is the bedrock of the family.

Herders’ Calling is a sweet, short film that allows us another glimpse as in The Sweetest Embrace: Return to Afghanistan, and observe lives and cultures so different from ours, yet as human as we are!

Two thumbs up!