An American Soldier at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

Huang Ruo and David Henry Hwang are Dynamite

By: Susan Hall - Jun 04, 2018

An American Soldier

By Huang Ruo

Libretto by David Henry Hwang

Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Loretto-Hilton Center

St. Louis, Mo.

June 3-June 22, 2018

The world premiere of An American Soldier by Huang Ruo and David Henry Hwang was presented by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis on June 3. Both men have long been interested in the cross over between Asian culture and Western. In the 2010 US census 3.8 million Chinese Americans were recorded. They have made an outsized contribution to America. In the music world, Yo Yo Ma comes immediately to mind. More than many other transplanted Americans, the Chinese Americans have creatively built bridges or silk roads between people of widely varying cultures.

The opera production of An American Soldier is polished and elegant. What made this first performance stunning was the textural variety on stage. Consider a rigorous and tense court martial, and a budding love of a Chinese American girl Julie for her neighbor in Chinatown, New York. Add to that an anguished mother’s sweet lullaby for her son, Ah Fat. Then there is the brutal torture and death of the young man they both treasure, Ah Fat, now known as Danny Chen. Not surprisingly, Opera Theater of Saint Louis is known for productions that soar.

The libretto by David Henry Hwang masterfully sets the entire opera in the present. We immediately meet Chen, sung with a graceful force by Andrew Stenson. He has died before appearing at the court martial of the Sergeant who killed him in Afghanistan. Yet Danny is a dynamic presence in the lives of everyone in the courtroom, whether or not he lives.

The selection of this true story, which was first developed as a one act opera, seems prescient in today’s world. Chen considered himself an American. Against his parents wishes, he enlists in the Army all the better to prove his deep feelings for his country. And it is precisely his Asian appearance, along with threats to other-colored black and Hispanic soldiers, that makes him a target for abusive racism in the military and elsewhere.

Danny’s mother has come to the trial to get justice for her son. Starting with the final scene makes us feel all the more strongly about the back story as it unfolds. Deep attention pays off.

Composer Huang Ruo makes choices that drive the opera ever forward, and yet allow us to savor moments, notes and words which enhance. Through- composition in the classic sense of that word is what he achieves. You want to see the opera several more times to appreciate all that the composer has done with music to create a masterpiece.

Clearly the collaboration with Hwang is a union of equals. Two arias stand out. One is a lullaby sung by Chen’s Mother early on as she recalls her son’s birth. At the very end of the opera, she reprises the aria and tells us in the words of the lullaby that her son will live forever. It is wrenchingly sung by Mica Shigematsu. A fierce tiger mother driven less by making her son successful than by making him safe, she ranges seamlessly from fury to fear to tenderness.

Testimony at trial that his family wanted to disown Danny for enlisting is contradicted by the very tone of the word 'disown'. It is often repeated with an extension of the “o” ending a phrase. In the orchestra, these endings give the music time to bridge from one scene to another without a curtained-off scene change, a break or a breath. The opera is in two acts, but there is no reason why it could not be performed straight through.

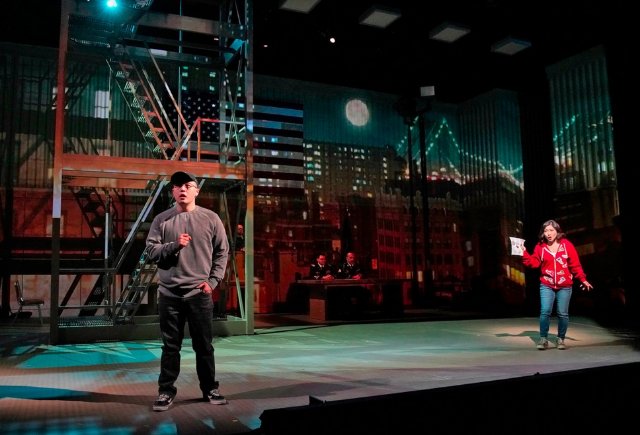

A fire escape structure with the Williamsburg bridge projected in the background is the setting for hometown boy scenes. We listen to Danny’s proud tones as he declares that he is not from China, but rather from Chinatown.

In the beginning the didgeridoo gives the flavor of an ancient story told by woodwinds. Patterns in the music are often three note phrases, plain with a decoration, which propulsively beat, but also have a liveliness in their shape. Under them, the incessant, steady beats of a drum give continuity and a military flavor. The double bass and tuba are both used for bottom patterns. Particularly satisfying is the composer’s creation of a double bass over and over against lovely notes of the piccolo and flute very far away. he

It is rare in contemporary opera to find the drama and music so successfully entwined. The composer does not underline phrases or exaggerate emotions. These are merged instead. Characters are not introduced. Rather they flow into and out of the story.

A perfect example of this creation is the role of Josephine Young, Danny’s special high school friend. The first few notes sounded like Madam Mao, a role Kathleen Kim has often sung. Then Kim remembers where she is, in Chinatown, a student about to go to college and realize the American dream. We have not heard or seen this side of Kim before. A full, rounded character, she sings simply and beautifully. The harsh notes are gone. She empathetically caresses each note and phrase. We are delighted to meet her in this fleshed out, unassuming form. Her range as an actress is wonderfully enlarged.

Josephine has a distinctive aria about the moon which we see in projections hanging as a quarter over Chinatown. It also hovers over the Afghan mountains where Danny also sees it and joins her in song. This parallel structure is achieved without tricks or tomfoolery. Its integration into the story allows us to be in many worlds at once and enriches our experience.

The talents of the Army characters do not immediately come to mind. This is a measure of the success of their performance. Nathan Stark as the Judge has a neutral demeanor at the start, but moves to a defense of the Army rather than the discovery of the truth. Wayne Tigges as the torturing Sergeant is darkly funny, evil, cruel and inventive in his torture techniques. We hate him and he was booed at curtain call, illustrating just how good he was in the role. Both men us a musically spoken speech, which the composer and librettist have created to have the effect of magically singing and speaking at once.

Supporting characters, each and every one, and the chorus of troops, give special interpretations.

Michael Christie conducting brought out all the details of Huang Ruo’s vision and carefully etched them into the action directed by Matthew Ozawa.

At a Works & Process presentation at the Guggenheim Museum, James Robinson, the co-stage director and dramaturg, spoke about the importance of this opera in today’s world. Clearly Robinson brought his abundant talents to mounting An American Soldier. Robinson's contributions to Opera Theatre of Saint Louis are evidenced by the status of Opera Theatre as a top producing company.