Pablo Picasso Died FiftyYears Ago

Global Exhibitions and Critical Evaluations

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 06, 2023

Well some people try to pick up girls

And get called asshole

This never happened to Pablo Picasso

He could walk down your street

And girls could not resist his stare and

So Pablo Picasso was never called an asshole

~Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers

As it turns out, Richman’s bashful, self-effacing, rock masterpiece continues to be charming and amusing but apparently, dead wrong.

There is an industry of books, articles and exhibitions that document that, if not an “asshole,” Picasso was at worst an arrogant misanthrope, surely a misogynist, and certainly a jerk.

Which is the flip side of the yin and yang of being among the most prolific and formidable artists of the 20th century. The point being a disconnection between great art created by deeply flawed individuals.

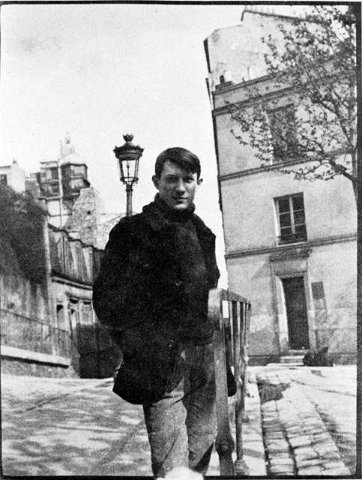

During his lifetime, at the height of fame and fortune, he basked in adoring critical and media attention as a stumpy, stocky bull of a man. As a macho ersatz matador he waved a red cape at women in erotic rituals of blood and sand. As an expatriate Spaniard in Paris he embraced the Minotaur as signifier of his creative persona.

It’s now been fifty years since his death (8 April, 1973). The 1961 book, “My Life With Picasso,” by Francoise Gilot (with Carlton Lake), the mistress who bore two of his children before departing, was shocking at the time. Her bedroom revelations were an opening salvo of ever more virulent character assassinations; arguably, deservedly so.

Picasso had a lifelong inability to provide support and empathy to friends, lovers and family. He shunned funerals, disowned his children, and failed to lift a finger to save the poet Max Jacob from the Nazis.

Over the years, tormented by picadors, the hide of Picasso has been gored by critics and biographers. Some fifty years on, posthumously, the flayed shade of the artist has lowered a weary head for the thrust of the sword by a matador/ critic, Sebastian Smee.

In a scathingly meticulous post mortem the headline of his Washington Post article asks “How good, really, was Pablo Picasso?”

The subhead reads “The exemplary modern artist died 50 years ago this month, and we’re still trying to clean up his mess.”

A few days later, and perhaps a dollar short, the populist biographer and art historian, Deborah Soloman, posted a gimmicky piece in the New York Times “Picasso: Love or Hate Him?” It bears the subhead “Fifty years after the artist’s death, a critic wrestles with her mixed feelings.”

Like plucking petals from a daisy, she delivers a check list of love or hate cliches. It’s weak tea compared to the swagger of Smee, well-researched, and on top of his game.

He leads with “Blue Picasso, pink Picasso, cubist Picasso, society Picasso, surreal Picasso, ceramist Picasso, late Picasso. Picasso in his underwear, Picasso in a bow tie. Harlequin Picasso, bullfight Picasso, the poets’ Picasso, the GIs’ Picasso. Anti-fascist Picasso, communist Picasso, peace dove Picasso. Prankster Picasso, heartsick Picasso, lecherous Picasso.

“Yes, Pablo Picasso was all over the place. He died 50 years ago this month at 91, and we’re still trying to clean up his mess.”

Mess! Oh really Sebastian. Problematic? To be sure. But a “mess” come now. Best to dial back on the hyperbole and let the facts tell the story. The first rule of journalism, however, is never let the facts get in the way of the story.

As to the facts, Smee informs us that “This year, in Europe and North America, around 50 exhibitions have been organized under the umbrella ‘Celebration Picasso 1973-2023,’ an initiative with the support of the French and Spanish governments. Some will try to solve the problem of the Spaniard’s extraordinary productivity by focusing on one year in his life (‘Picasso 1906: The Turning Point’ at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid) or even just three months (‘Picasso in Fontainebleau’ at New York’s Museum of Modern Art). Others — too many to list — will tame him by matching his works with those of other artists (El Greco, Max Beckmann, Nicolas Poussin, Joan Miró), with writers (Gertrude Stein) or with lovers (Fernande Olivier, Françoise Gilot). In June, the Brooklyn Museum will mount a show, co-curated by the comedian Hannah Gadsby, looking at Picasso through a feminist lens, placing him beside such artists as Cindy Sherman, Ana Mendieta and Kiki Smith.”

Picasso lived to a ripe age and was creative till the end. The late work is problematic hovering between kitsch, repetition, and self pity. It’s a maudlin tale of the pampered artist, isolated by gatekeepers, feeding on himself, and out of touch with other artists. As a national monument he was essentially cast in bronze and erected to a pedestal.

The seminal book on this subject is the Marxist historian John Berger’s 1965 “The Success and Failure of Picasso.” The essential and most detailed study of Picasso is John Richardson’s four volume biography.

Of which Smee states “Richardson, who died in 2019, had a credible theory that Picasso saw himself as an exorcist or shaman. The idea was grounded in the artist’s childhood and in things he later said about his 1907 breakthrough, ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.’ The Spaniard was interrogating, Richardson argued, ‘the atavistic misogyny toward women that supposedly lurks in the psyche of every full-blooded Andalusian male.’ “

The oeuvre, ultimately what really counts, is staggering. He made around 13,500 paintings, 100,000 prints, 700 sculptures and more than 4,000 ceramics. That doesn’t include the forgeries.

While the general public may embrace, enjoy and comprehend Picasso’s early Blue and Rose periods they are flummoxed by cubism which, in collaboration with Georges Braque, came hard on the heels of the gut wrenching and violent breakthrough “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” of 1907.

The less they know about art the more reliant the public is on biography. One thinks of “Lust for Life” (1934) and “The Agony and the Ecstasy” (1965) by Irving Stone. His biographies did much to promote the work of Vincent van Gogh and make Michelangelo more accessible. The books became popular films.

The romance of Paul Gauguin in Tahiti has been embraced as exotic and erotic. Today, that once universally adored work is regarded as having been produced by a pedophile and sex tourist.

Norman Mailer and Arriana Huffington, who had no qualifications to do so, cranked out turgid and truly awful books on Picasso. The primary source for Huffington’s pulp fictive was the bitter, failed artist, Gilot. Not surprisingly the book, which sold well, was DOA. Directed by James Ivory, it was the source for Anthony Hopkins’ worst film, “Surviving Picasso” 1996.

Much art history is daunting to slog through. This is particularly true of formalism which focuses on the work and not the creator. That approach proves to be relatively accessible compared to the deconstructionists, ersatz philosophers, and social justice harridans.

Compared to which it was delightful recently to read Sue Roe’s evocative “In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist Art” (Penguin Books, New York, 2014).

The accessible and witty book conflates biography, anecdotes, and sharp critical analysis. She provides a well defined time line through the sociology of the most seismic movements and stylistic shifts of early 20th century French art history.

Roe mixes a heady and intoxicating cocktail of artists and their lovers, patrons and dealers, critics and poets, shaken not stirred, in the poor, less populated pinnacle of Paris in the shadow of Sacre Coeur. At the turn of the century there were still the orchards and windmills that van Gogh had depicted.

Cheap rent in ramshackle hovels allowed starving artists to hunker down with Apaches and prostitutes. Depravity, criminality and creativity intermingled fluidly. For artists there was ready access to models and lovers. For Picasso this was a surprise. The norm for bachelors was to pay for pleasure in the barrio gotico of Barcelona. Prostitutes were a consistent subject in his work. He studied them in prisons and hospitals. Those who wore distinctive white caps were inflicted with syphilis. Ironically, these paintings are easily confused with Madonnas.

Scholars have attempted to identify the standing blonde woman bathing in a metal pan in Picasso’s 1901 “Blue Room.” She may have been his first live-in girlfriend in a small, squalid studio in the Bateau Lavoir. It was the legendary warren of spaces that housed artists including the Italian Amadeo Modigliani.

The complex was the setting for the most famous and raucous art event of the 20th century. There have been many accounts of the dinner party hosted by Picasso and Fernande Olivier in honor of the outsider artist Henri Rousseau.

Roe provides a thumbnail of the occasion. Like much of her book it is familiar territory. The thrust and brilliance of the book, however, is the deft stitching together of so many threads to create a richly colorful tapestry of the era and its protagonists.

The bibliography and footnotes extensively document the fine-honed details of her narrative. She has the ability to pin down the day and time of a key interaction or event. While Picasso, his collaborator Braque and primary rival Henri Matisse are featured, there’s a well stocked undercard of Fauves; Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, and the separate but equal, Modigliani.

The commonality is grinding poverty. Sales came in dribs and drabs. There were small local galleries like that of Berthe Weil the first to show so many 20th century masters. As a market emerged there were predatory dealers like Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. They bought from studios and, for a time, an artist might be relatively flush. Treated as inventory the artists got no cut as prices rose. Because of this exploitation Picasso was vengeful with dealers in later years.

When dealers and collectors struck hard bargains, from the beginning, Picasso held back key works. To settle his estate a portion became the basis of the Picasso Museum in Paris. With taxes settled the rest of the works were divided among his heirs.

In Paris, Picasso retained his Catalan friend and poet, Jaime Sabartés y Gual, as secretary and gate keeper. It was an abusive relationship over many years. Picasso would, from time to time, brush him off or fire him. Then on a whim take him back. Rather than pay bills the artist opted for barter. In this manner Sabartés acquired a major collection primarily of early work. It was donated to found the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

During summers, when artists escaped the heat of Paris, Roe takes us on vacation with Picasso in Spain or to Collioure with Matisse and Derain. This time was focused on preparing work for the all important annual Salon d’Automne. The author provides vivid descriptions of key works and evolving stylistic developments. She delineates how the rivals Picasso/ Braque and Matisse continued to experiment while the Fauves, Derain and Vlaminck, did not.

Enter the Steins: Gertrude, Leo, Michael and his wife Sarah. Initially, Gertrude and Leo marauded together. Eventually, Leo proved to be bombastic and more conservative. Leo never got much beyond Cezanne and they divided the collection when she focused on Picasso.

With humor Roe describes the hefty Gertrude hiking up to Picasso’s Montmartre studio for endless sittings of her portrait. Eventually, he wiped out the face and painted her from memory.

While Gertrude championed Picasso the sisters Cone, Etta and Claribel, supported Matisse. They brought their collection home and later donated it to the Baltimore Museum of Art. The other major Matisse collector was Moscow’s Sergei Shchukin. During the Russian Revolution the collection was confiscated with Shchukin designated as its “curator.”

There is a tendency for the bourgeois art appreciator to regard ‘la vie boheme’ as colorful and glamorous. Perhaps that’s what I thought as a teenager visiting an outdoor café in Montmartre. I was serenaded by a couple, he squeezing an accordion, and she singing Piaf with blousy bathos; while a gypsy tried to sell me a rose for my then sweetheart.

A brutal new book “Picasso the Foreigner,” by Annie Cohen-Solal pricks that balloon. A New York Times review by Hugh Eakin states that, “For decades after his death, it was assumed that he preferred his expatriate status. But in 2003, the art historians Pierre Daix and Armand Israel published the startling contents of Picasso’s unknown French police file. French authorities had surveilled the artist at the beginning of his career as a suspected anarchist, but that wasn’t all. In the spring of 1940, at the height of his fame, they also denied his application for citizenship. A police official ruled that Picasso ‘does not qualify for naturalization.’ France’s most influential 20th-century artist would die a Spaniard…

”According to Cohen-Solal, for decades the country’s leading national museums simply refused to exhibit or collect him. When the Louvre was offered ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ as a gift in 1929, it turned it down. By then generally recognized as a turning-point masterpiece, the painting went instead to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as did a trove of invaluable Cubist works.

“The tide only turned in France after World War II, when Picasso, by then a box-office draw, began donating works to French provincial museums outside the academic sphere. He knew what generosity was buying him. It was seeding public ground, growing an audience, spreading his brand. He knew the establishment would eventually cave to popular demand, grant him admission, which it grudgingly did, but so late in the game that it had little of his best past work to show.”

Eakin writes that Cohen-Solal debunks myths. “In place of the seedy Belle Epoque glamour usually associated with Picasso’s first years in Paris, she presents a paranoid and xenophobic city, still reeling from a decade of antisemitism and anarchist violence. Montmartre, we learn, was crawling with police informants with names like Finot, Foureur, Bornibus and Giroflé; as for the Bateau-Lavoir, the much-mythologized artists’ building where Picasso lived and worked during his first cubist breakthroughs, it was in reality ‘one of those shameful habitations that the capital offered its immigrants and marginals.’ In this unpromising milieu, the young Picasso, with his broken French and outcast friends, struggled to avoid arrest or even expulsion…’ “

Le Bateau-Lavoir is located at No. 13 Rue Ravignan at Place Emile Goudeau, just below the Place du Tertre. A fire destroyed most of the building in May 1970 and only the façade remained, but it was completely rebuilt in 1978.

Formerly a ballroom and piano factory, Bateau Lavoir was divided into 20 small workshops in 1889. Distributed along a corridor, small rooms were linked without heating and with a single point of water. The name “Le Bateau-Lavoir” was coined by French poet Max Jacob. On stormy days, it swayed and creaked, reminding people of washing-boats on the Seine, hence the name.

To be sure, Picasso’s alien status made palpable concerns about possible deportation. No doubt it factored into survival strategies during two world wars and Nazi occupation. “Artists Under Vichy: A Case of Prejudice and Persecution” by Michèle C. Cone (1975) is a compelling study of that issue.

For example, some writers, painters, and sculptors accepted invitations to visit Germany on official junkets. Collaborationist authors were invited to Weimar in November 1941 for a congress of European writers, and painters (including André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Kees van Dongen) and sculptors (Charles Despiau, Paul Belmondo, and others) went on a gala tour of Germany that same month.

Consider that the American Jewess, Peggy Guggenheim, fled Paris while Gertrude Stein remained put. Though Picasso did not embrace the Nazis he was a tolerant tourist attraction for them. Jean Cocteau was a gadfly go between while Maurice Chevalier serenaded them.

It’s complicated. As Allen Ellenzweig states in part “Journalist Janet Malcolm’s 2007 exposé in The New Yorker, and the book that expanded on it, ‘Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice,’ forced me to reconsider Stein and take her measure fresh. Malcolm explained how Stein and Toklas had been protected during the Occupation by a well-connected anti-Semite collaborator, committed Catholic, and conflicted homosexual, Bernard Faÿ, with whom Gertrude had been close friends for more than a decade and who had personally interceded on her and Alice’s behalf with Maréchal Philippe Pétain, the collaborationist leader of Vichy. Faÿ, director of the Bibliothèque Nationale during the Occupation, also secured Stein’s Paris art collection from the Germans. Recent scholarship by Barbara Will, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, paints a warts-and-all portrait of Gertrude and her conservative, anti-Roosevelt, fascist-leaning politics in the interwar period…

“Stein famously said of Hitler in a 1934 interview that ‘[he] should have received the Nobel Peace Prize … because he is removing all elements of contest and struggle from Germany. By driving out the Jews and the democratic and Left elements, he is driving out everything that conduces to activity. That means peace.’ After parsing this statement’s perversity, Barbara Will concludes that for Stein’s contemporaries, her ‘pontifications’ of this period were ‘not clearly ironic but apparently deeply felt.’ “

After the war, Picasso was a lip-service communist ensconced in bourgeois luxury.

And so it goes with dark tales of modernism and its discontents. Hopefully, at the end of the day, we are left with the art.